Dantemag and Belstaff

November 25, 2020

Greenwashing our conscience?

November 10, 2021Italian master distiller Stefano Baseotto talks to Massimo Gava and takes us on a trip into gin land and explains the origins and the varieties of this ever so popular drink.

In the complex world of distillation, the varieties of eaux de vie produced over the centuries from different ingredients are divided into two main categories, the young ones that tend to use fruits like pears, cherries, grapes as a starting point and those that need aging, like brandy, cognac, armagnac, old rum and whisky.

However, between these two there is another one which, thanks to its increasing popularity, has created a kind of a world of its own. The ever so popular Gin.

Despite all the different types of gin available worldwide that use an end-less variety of added flavours, the one indispensable element to making gin is the berry of the juniper, a coniferous tree that grows in mildly cold climates around the world and even in ancient times was known for its medicinal benefits as well as being used extensively in cooking.

Despite all the different types of gin available worldwide that use an end-less variety of added flavours, the one indispensable element to making gin is the berry of the juniper, a coniferous tree that grows in mildly cold climates around the world and even in ancient times was known for its medicinal benefits as well as being used extensively in cooking.

Italian juniper is considered to be the best for its taste but there are also some differences we need to take into account, namely which part of Italy this precious berry comes from and, equally important – at what period of the year it is harvested as this can also determine what characteristics the final product will have. The top-rated juniper according to the experts comes from Tuscany; its summer time berry will impart notes of resin, while an autumn harvest will give a citrus and spicy aftertaste and then the early winter berries produce a fuller spicy taste with strong notes of juniper. The Umbria berry has more of an aftertaste of ripe fruit, with some other times of the year produc-ing notes of more exotic fruit. Obviously, the final combination of berry and aromatics depends on the wizardry and skill of a master distiller who will get the best out of each area’s microclimate and terrain.

Italian juniper is considered to be the best for its taste but there are also some differences we need to take into account, namely which part of Italy this precious berry comes from and, equally important – at what period of the year it is harvested as this can also determine what characteristics the final product will have. The top-rated juniper according to the experts comes from Tuscany; its summer time berry will impart notes of resin, while an autumn harvest will give a citrus and spicy aftertaste and then the early winter berries produce a fuller spicy taste with strong notes of juniper. The Umbria berry has more of an aftertaste of ripe fruit, with some other times of the year produc-ing notes of more exotic fruit. Obviously, the final combination of berry and aromatics depends on the wizardry and skill of a master distiller who will get the best out of each area’s microclimate and terrain.

But when did it all start?

But when did it all start?

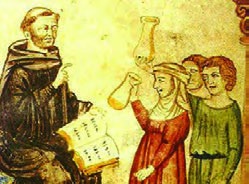

We can trace the first origins of the drink at the Scuola Salernitana, a late medieval medical school, the first and most important of its kind, which grew out of the dispensary of a monastery founded in the 9th century. Situated on the Tyrrhenian Sea, in the southern Italian city of Salerno, it rose to prominence in the 10th century, becoming the most important source of medical knowledge in Western Europe at the time.

The monks were the first to discover the medicinal benefits of this coniferous plant and it was to preserve supplies over the year that they came up with the idea of putting the berries in eau-de-vie.

In fact, one of its treatises the Compendium Salernita dated 1055 mentions a ‘distilled wine with added juniper infusion”. Then later in 1250 in his Der Naturen Bloeme Volkeren Jacob Van Maerlant talks about the beneficial effects of the juniper berries and the wine to cure stomach pains. The earliest known written reference to ‘genever’ (Latin juniperus) in the 13th-century encyclopaedic work Der Naturen Bloeme (Bruges) by Jacob Van Maerlant, with the earliest printed recipe for genever dating from 16th-century work, Een Constelijck Distileerboec (Antwerp).

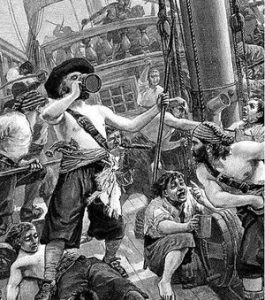

The physician Franciscus Sylvius has been falsely credited with the invention of gin in the mid-17th century, although the existence of genever is confirmed in Philip Massinger’s play The Duke of Milan (1623), when Sylvius would have been about nine years old! Our word ‘gin’ is a shortened anglicisation of that Old Dutch word genever, which itself nowadays refers to a malt-wine based spirit still popular in the Netherlands but different to our modern gin. The false myth grew up that gin came from Geneva because of the word’s similarity to the city’s name but this is what is called folk etymology and has no basis in fact, as we have seen. It was also known as ‘Dutch Courage’, as Dutch soldiers traditionally took a shot to face battle. And in modern English it now has the connotation of false courage since the effect of the alcohol was temporary. It was thanks to William of Orange, himself a Dutchman, who ruled with Queen Ann from 1689 to 1702 that gin in Great Britain really became popular. Alongside coffee shops there were an abundance of gin-shops as well. In order to isolate his French enemies he forbade the import of all foreign distilled drinks, especially cognac, thereby encouraging the use of cereals in distilling.

The drink became so important at the time that even worker’s salaries were paid in part in gin. Production of gin rose to a staggering 70 million litres a year and one can only imagine the effects this had on public order across a population of only seven million. Indeed over the subsequent decades crime rose to such an extent that Parliament passed various Gin Acts from 1730 onwards aimed at reducing consumption of a liquid that was considered to be the root cause of this rise in crime – with limited success, by the way. Indeed public drunkenness and disorder were so rife that gin became known as “mother’s ruin” , culminating in the famous English satirical illustrator Hogarth’s grotesque engraving “Gin Lane” of 1751, depicting the misery brought on by over-consumption. It had become akin to our modern drug epidemics.

Luckily we have moved on from those excesses and specialised craft gins and mini-distilleries are mushrooming everywhere. The most popular is using gin with mixers and in cocktails and what must be that most iconic of drinks -gin and tonic, a quinine based mixer originally use by the British soldiers posted in India. What, then, makes modern gin-making so versatile and produces such sensory journeys for the modern gin drinker? We have established the juniper berry is an essential basis for any gin. It is then up to a master distiller to choose which secret ingredients he or she adds in order to give that predominate in taste and aroma. There is no minimum alcohol content and the maximum allowable level of sweeteners is higher at 20 g/l. Finally there is “Gin”, commercially referred to as “Compound Gin”, which is just a simple infusion of juniper berries, botanicals, spices, fruit and aromatics both natural and artificial – there is therefore no need to distil the mixture of ingredients. This type of gin is a coloured liquid unlike the other two, which are clear.

Generally speaking gin has an initial resinous taste to the palate that is softened a moment later by the aromas and spices the master distiller has used. Even the more refined and elegant gins have not lost this strong initial hit admittedly, the pungent factor has given way to a silkier taste nowadays but do not expect a completely smooth impact in your mouth at first. Be aware that a good gin should have a dry aftertaste, without any aggressive notes that might ruin the pleasure of the botanicals and aromas selected to make that craft gin distinctive.

The reason there are so many varieties of this drink is because basically, let’s face it, there are different strokes for different folks. However most gin aficionados and experts prefer the classic recipes adhering strictly to the three processes we have talked about. London Dry Gin as a process producing the highest quality seeing as there are practically no sweeteners allowed. But ‘de unique flavour to their creation; angelica root, liquorice, cardamon, coriander seeds, citrus aromas are just a few of an endless array of possibilities. These additives are called botanicals. However they should not completely overwhelm as there are strict European directives as to minimum levels of juniper for it to be officially classed as a gin.

The law recognises three basic processes according to official minimum re-quirements. “London Dry Gin” or “London Gin” is produced in traditional stills from one single distillation. It uses a food-grade alcohol, which in Italian we call ‘Buon Gusto’, re-distilled with a mixture of plants or parts of a plant, spices, fruit and aromatic herbs, depending on what recipe is being used. The gin must have a minimum alocohol content of 70 degrees with a possible addition of only 0.1 g/l maximum of sweeteners and there is no requirement for the juniper to predominate. London Gin can also be produced outside the UK.

Master distiller Stefano Baseotto

Ingredients can also be previously infused in food-grade alcohol or can be added directly to the upper part of the still during the distillation or a combination of both processes.

Gustibus non disputandum est’ (To each his own)! We hope that armed with this extra insight into the great art of gin-making you will be able to choose your next bottle of gin wisely. And always remember that spirits, eau de vie or aqua vitae all allude to the life that courses through your body, the “water of life’, your spirit and soul! May you appreciate the skill and subtle nuances of flavour – always in moderation, of course and may you have a warm and glowing festive season!

Chin, Chin – Gin, Gin!