Rio Voluptuoso, Rio Carinhoso

February 22, 2022

The Eternal Spring of Vivaldi

April 27, 2022Flavio Lirussi for DANTE explains how cities around the world are leading the charge against climate change in fascinating and innovative ways.

The ‘100 Resilient Cities’ network defines urban resilience as “the ability of individuals, communities, institutions, businesses and systems within a city to survive, adapt, and grow, no matter what kinds of chronic stresses and acute shocks they experience.” According to Nigel Tapper, a world-renowned climatologist and Nobel laureate in 2007, “A city is resilient if it is quickly protected against climate shocks.The key is to have credible plans, supported by secure funding, with integrated and intersectoral projects.”

The beginning of the 21st century has been characterised, in many countries, by economic crises, an increase in inequality, aging populations and urbanisation, but there is a phenomenon that involves every country on a global level: climate change. At the COP24 (Katowice 2018), the World Health Organization presented a report on health and climate change outlining recommendations to maximise health benefits from combating climate change and interventions to minimise its worst health effects. The drivers of climate change – principally fossil fuel combustion – pose a heavy burden of disease, including a major contribution to the 7 million deaths from outdoor and indoor air pollution annually.

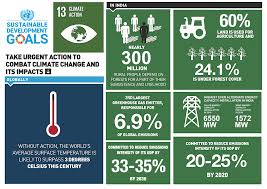

The fight against climate change is one of the seventeen sustainable development goals of the 2030 Agenda of the UN (Goal 13). According to a study published in Nature, heat waves and rising sea levels will bring several urban cities with millions of inhabitants to their knees in the coming decades: from Miami to Shanghai, from Dubai to New Delhi. Given that the human and social impact is enormous, it is precisely in these territories and cities that the fight against climate change must begin, in the sense of their resilience. Not by chance, Goal 11 of the 2030 Agenda calls to “make cities and human settlements inclusive, safe, resilient and sustainable.”

Strategies to fight the impact of climate change can be grouped into three categories: urban reforestation, man-built barriers and natural ‘infrastructures’, and new technologies applied to the environment. Financial products such as green bonds, fiscal policies to incentivise clean energy sources and discourage the use of energy sources of fossil origin, are also part of the picture. Not to mention the social movements (for example, ‘Fridays for Future’) which are able to influence the public debate and action against climate change. The ultimate goal is to halve global greenhouse emissions by 2030 and to reach the zero emission target by 2050. Carbon emissions created by human activity trap heat in the atmosphere, causing global temperatures to rise and the global climate to change.

Urban reforestation is part of the urban forest strategy of the city of Melbourne to reduce exposure to hazards such as heatwaves and flooding. The strategy aims to adapt the city to climate change, mitigate the urban heat island effect by bringing the inner-city temperatures down, create healthier ecosystems, become a water-sensitive city, and engage and involve the community. This will be achieved by increasing canopy cover from 22% to 40% by 2040. The green roofs project is also part of the strategy: green roofs enhance the urban landscape, create social and leisure environments, but above all, help cool hot cities, reduce storm water drainage and insulate buildings all year round.

In the south-east of China, Liuzhou Forest City will have all the characteristics of an urban settlement fully self-sufficient in terms of energy, with geothermal energy for interior spaces and the use of solar panels on the roofs for renewable energy. But what is striking is the presence of plants and trees on all buildings, whatever their size or use. Overall, Liuzhou Forest City will host 40,000 trees and about one million plants of more than a 100 species. This will allow the production of about 900 tons of oxygen and the absorption of 10,000 tons of CO2 and 57 tons of fine dust each year. Thus China, the world’s biggest energy user and greenhouse gas emitter, has decided that development must respect and protect its environment. Another huge project fosters links between nine cities in Guangdong, Hong Kong and Macau to forge the world’s biggest urban area with 70 million people. The master plan purposes to develop the Pearl River Delta into a sustainable innovation hub, with autonomous zero emission vehicles, flying taxis, artificial intelligence, robotics and clean energy.

Green wall. FAO

In Africa, the Great Green Wall aims to stop desertification and to recreate environments favourable to cultivation and life in the sub-Saharan area of the settled populations. When completed, the great green barrier will be 8,000 km long and 15 km wide and will extend from Senegal to Ethiopia. An even more ambitious project is the Great Green Wall of Cities, coordinated by the architect Stefano Boeri and supported by FAO, the Royal Botanic Gardens Kew and other organisations. The aim is to build next to 90 cities from Africa to Central Asia 500,000 hectares of new urban forests and 300,000 hectares of natural forests to maintain and restore by 2030. But not only that: the aspiration is to extend to other continents as well, namely Europe, the ability of big cities to create large forested areas around and within their urban fabric over the next few years.

Architect Boeri was indeed the first to create the ’vertical forest’ in Milan, a complex of two residential tower buildings located in the business district. It contains 700 trees and 20,000 plants. It is a metropolitan re-forestation project that aims to increase plant and animal biodiversity, and to contribute to the mitigation of the microclimate. It allows the absorption of CO2 and particulates, produces oxygen and reduces energy consumption. As cities produce 75% of CO2 and forests absorb 45%, bringing forests into the city is a win-win strategy!

Paris too is on the front line of combating climate change, mainly heat waves, but also of reducing pollution by increasing green spaces within the city. Paved areas are being replaced by green spaces in many schools, and these areas will be accessible to all Parisians in case of heat problems. In addition, Paris is going to host an urban garden that covers a roof covering 14,000 sq metres, to be opened in the spring of 2020. Located at the top of Pavilion 6 of the Parc des Expositions in Porte de Versailles, this huge garden will be the largest of its kind in the world as well as the largest urban farm in Europe. “The goal is to make the farm a globally recognised model for sustainable production,” says Pascal Hardy, founder of Agripolis, the urban-farming company at the heart of the project. “We’ll be using quality products, grown in rhythm with nature’s cycles, all in the heart of Paris” he adds. In fact, the garden will host more than thirty species of different plants, all grown using organic farming methods. Moreover, thanks to the fact of cultivating ‘zero km’ products, the garden will have a very small carbon footprint.

In 2013 New York suffered the devastation of Hurricane Sandy. BIG U, a barrier system designed to protect Lower Manhattan from tidal surges and rising sea levels, is now underway. It will protect ten continuous miles of coastline coinciding with a densely built and vulnerable urban area. Big U is being built following in part the abandoned elevated railway, transforming it into a public space and green landscape with viewing points. The project is based on two concepts: social infrastructure and aesthetic sustainability. The Big U will not only make the waterfront more resistant to extensive flooding due to climate change, but also more accessible to citizens. It is a very good example of how a resilient city can combine flood defences with environment protection, beauty, and socialisation.

Man-built barriers are just one of the possible solutions to withstand the damaging effects of climate change. But how about using natural ‘infrastructure’? The recently published guide Building Urban Resilience with Nature provides practical examples and measures that local leaders can take to accelerate the uptake of nature and natural infrastructure as key drivers of resilience in their cities. The document explains that “nature is fundamental to the functioning of cities – through its delivery of a wide range of goods and services including food, water, air quality, climate regulation, protection from natural hazards, measurable health and economic benefits.” On the other hand, natural infrastructure can be used by cities to meet specific goals like gallons of storm water filtered, storm surge reduction, or heat island mitigation. Moreover, nature-based infrastructure may provide a broad array of co-benefits to the community, such as creating new parks and improving the equality and health of underserved neighbourhoods.

Proctor Creek, a tributary of the Chattahoochee River, originates in downtown Atlanta. The creek and surrounding lands have experienced decades of environmental degradation including erosion, pollution from illegal dumping, and high bacteria levels from storm water runoff and sewer overflows. Atlanta’s resilience strategy is to build the new Proctor Creek Greenway trail, with the goal of creating 500 new acres of publicly accessible greenspace across the city by 2022. Equipped with cycling and pedestrian lanes, the Proctor Creek Greenway will facilitate physical exercise and healthy living, enhance Atlanta’s natural assets, and foster economic development in an area of the city which faces poverty-related urban challenges. The resilient Greenway project will also leverage green infrastructure to curb flooding and runoff.

Panama City’s geographic position is characterised by heavy rains during the rainy season which brings about ongoing floods affecting the lowest coastal zones. Floods tend to concentrate in the areas where the basins have been canalised and cemented over. Part of the resilience strategy includes the Green-Blue Micro-Infrastructure Programme: floods can be reduced by means of interventions intended to encourage bio-retention in parks and easement areas, such as islands, roundabouts and open spaces. These facilities allow for storm water runoffs to build up and seep through plants and soils with a temporary storage layer. Waters usually spreading across houses and commercial premises, would then be diverted to planned underground areas by infiltration. Another project is the extension of the Coastal Belt and the System of Open Spaces along the Panama Bay 20 km waterfront, and transformation of the coastline zone through the introduction of green infrastructures.

The District of Panama also includes a mangrove forest. Mangroves can be regarded as the quintessence of a natural infrastructure. They reduce annual flooding to more than 18 million people worldwide; without mangroves 39% more people would be flooded annually. Vietnam, India, Bangladesh, China, and the Philippines are the greatest beneficiaries of this effect, whereas China, USA, India, Mexico and Vietnam receive the most benefits in terms of annual prevented damage to property. Mangroves reduce exposure and vulnerability. These combined effects are crucial for countries in West and East Africa, Central America and the South Pacific. Mangroves protect coastlines by preventing erosion and reducing the power of waves, storm surge and flooding. Their aerial roots retain sediments and prevent erosion, while the roots, trunks and canopy reduce the force of oncoming wind and waves and reduce flooding. It is estimated that a 500 m wide mangrove forest can reduce wave heights by 50–100%. Mangrove restoration therefore can be a highly cost-effective strategy for risk reduction.

Chinese-Academy-of-Engineering-CAE.j

Finally, another tool to combat the devastating impact of climate change in some areas of the planet is adopting innovative technologies. Nothing to do with artificial intelligence or robotics. And this time the goal is really impressive: converting desert sand into fertile soil! The experiment is taking place in North China’s Inner Mongolia: corn,tomatoes, sorghum, sunflowers are already being grown there, and 200 hectares of desert have been transformed into fertile land in just six months. How is that possible? Chinese scientists have developed a paste made of plant cellulose that, when combined with desert sand, is able to retain air, water and nutrients which are sufficient for plants to grow. The paste is non-toxic, ecological and affordable. This model can be exported and, indeed, is even being tried in one of the most extreme climates on earth: the Abu Dhabi desert!

New technologies, urban reforestation, man-built and natural infrastructures are all weapons we must use to combat climate change in our cities. Continuing urbanisation makes cities important foci of action for climate and health. Eco-friendly financial products, political will and social movements can also help. Christiana Figueres, former head of the UN Framework Convention on Climate Change argues, “The social and economic reversals are aligning but it’s a race against time.” The next ten years are crucial, and the quickest transition in history is needed to save our planet – and ourselves.

*Flavio Lirussi is a former Senior Advisor of the World Health Organisation and Lecturer at the Masters in Science Communication, University of Padua, Italy

People are interested in reading also. The Zoo. The globe-localisation.

https://www.waterstones.com/book/the-zoo-globe-localisation/massimo-gava//9781527268623

https://www.ebay.co.uk/itm/143752055296.