Green Revolution – How Cities Can Rise to the Challenge

April 27, 2022

ART COMES IN ALL SHAPES AND FORMS.

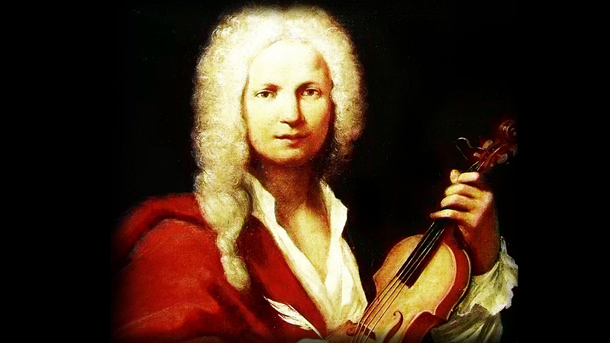

April 27, 2022Now so ubiquitous as to border on cliché, the works of the Italian Baroque master Antonio Vivaldi were virtually unknown and went unheard for almost two centuries. Philip Rham explains why you should count yourself lucky the next time that familiar “on-hold” music starts up in your ear. It is actually a privilege generations before you were denied.

S

“Spring is sprung, the grass is riz, de boid is on de wing! But dat’s absoid, I always hoid, de wing is on de boid!” to quote a certain anonymous poet of The Bronx! It is true that spring is epitomised by birdsong as the males set out their territory, attract females, create broods and protect their offspring – human life in microcosm, in fact. Indeed spring is such a relief after winter – cold, grey and enclosed as it is – that life bursting through, Persephone clawing her way back from the Underworld, makes you want to get out there and sing just like those birds. And where could it be easier to find that empathy of joy than in music? Composers have always found expression in an evocation of spring or at least naming their work after it as it refers vaguely to a sense of rebirth.

Antonio Vivaldi

For instance, we have Schumann’s “Spring Symphony”, Beethoven’s “Spring Sonata” for violin, Haydn’s oratorio “The Seasons”, and getting closer to a direct representation, with its cuckoos and various waking spring birds, is of course Beethoven again in his sixth symphony, “The Pastoral.” But the one piece that immediately springs to mind – forgive the pun! – is, of course, Vivaldi’s iconic, nay, dare I say it, hackneyed, “Four Seasons”. Oh no, I hear you say, not that muzak for lifts; not that “Your-call-is-important-to-us-one-of-our-operators-will-be-with-you-shortly” plinky-plonk tune. Let me, however, try and convert you back to listening and appreciating this first piece of film music, tone poem or programme music, call it what you will.

Vivaldi was at the forefront of Venice’s musical life in the early decades of the eighteenth century. The city-state’s economic power had already waned, but Antonio Lucio Vivaldi, born in 1678, was creating a name for himself. His father had been a violinist at St Mark’s and Antonio, being the youngest of six, was destined (as was the tradition then) to go into the church. Even though he was finally ordained in 1703, he was excused from saying mass as he suffered from what he called “strettezza di petto”, which is now considered to be bronchial asthma, a condition not helped by the dank waters of Venice. However, being known as the “Prete rosso” (red priest) – on account of the red hair he inherited from his father – never prevented him from pursuing his musical career as a violinist and composer. It is thought he was the star pupil at St Marks under Giovanni Legrenzi, so much so that in this most prestigious of musical cities he was appointed “maestro di violino” at Conservatorio dell’Ospedale della Pieta. This conservatory was a peculiarly Venetian phenomenon, being an orphanage for foundlings, exclusively girls, who were encouraged to sing and play instruments, to such a proficient level that their concerts were the highlight of the Venice Carnival and their fame extended to the whole of Europe.

It was also at this time Antonio started composing – operas, church music (his “Gloria” and his “Magnificat” being the best known and performed), sonatas and concertos. In his life he wrote 350 concertos overall for various instruments including one of the first for the clarinet. But the vast majority (230 of them) were for the violin, naturally enough, as he could then be the soloist or indeed hand the solos over to some of the very talented girls at The Pieta. In recognition of this he was appointed “maestro de concerti” there.

Indeed, it was the concerto where Vivaldi made his mark. The rest of Europe was still in awe of Italy’s predominance in musical culture with Albinoni in Venice, Tartini in Padua, the Scarlatti father-and-son duo in Naples and beyond, and not forgetting the great Corelli who remained supreme, especially in the Northern countries of Europe and in more conservative Rome. But it was Vivaldi who extended the form of the concerto. Originally a concerto was just a concerto grosso, a body of strings playing together or divided into smaller groups. It was Vivaldi who took an idea from Torelli and created the concerto as we know it today, where one solo instrument is pitted against the rest of the orchestra. His composing style is remarkable for his daring use of harmonic invention and technical use of syncopation, pizzicato (plucking the strings) and very precise dynamic instructions. Vivaldi was well aware of his daring, he certainly wasn’t shy and retiring; indeed, he was well known for driving a hard bargain in his continual quest for patrons since the Pieta position had to be renewed every year. Thus for security, during his lifetime Vivaldi sought out and buttered up many patrons, including the Habsburg monarch Charles VI, among others. This became even more urgent when the Pieta finally had enough of him after his travelling away from Venice and his consorting with the famous Giraud sisters, with whom he was reputed to have had dalliances, as well as composing operas for Anna “La Girò”.

Self-importantly – but, as we shall see, justifiably – he named a set of concertos “L’estro armonico” (1711). Estro has many meanings, ranging from inspiration, to flight of fancy, to impulse, to sexual heat (compare our word oestrogen) and even the scientific name for a gadfly. In a way, this gamut encapsulates everything about Vivaldi’s spirit and his approach to music. In the same vein he called another set of concertos “Il Cimento dell’armonia e dell’invenzione” (The Contest/Testing of Harmony and Invention) written in 1720 (published in 1725). This is where we finally find our famous Four Seasons.

At this time Vivaldi was at the height of his powers and naturally enough, the first four concertos of this set feature the violin with concerto ripieno – full string orchestra – whose first violin takes a leading role as well. What many people are not aware of is that the programmatic nature of these pieces is reinforced by a set of sonnets, whose authorship remains disputed though the consensus leans towards Vivaldi actually having penned them himself in his Venetian dialect. What impresses even more are his annotations in the margins of the manuscript score, such as “the fleeing prey”, “the barking dog” and “the sleeping drunk”.

Our main concern here, of course, is Spring and we see his marvellous talent for creating a picture. Above is the original sonnet, with my translation to follow:

As you can see, this simple but charming sonnet creates clear distinct pictures, ripe for musical interpretation, and how magnificently Vivaldi rises to the occasion! The concerto is in the traditional Fast-Slow-Fast, three-movement form.

The first movement relates to the first two verses and immediately after the unison strings announce the spring and bounce of new life again, you can hear the violin and the lead violin of the orchestra, weaving their birdsong in and out, over and above each other. The strings in a soft flowing carpet of sound, with the chug of the cellos, create the burbling splashing stream. Suddenly the escalating strings’ tremolando ratchet up the pressure of the dark clouds and the birds (the solo violins) can sense the looming storm. It passes and the violin and strings resume their joyful singing and dance to finish the movement off.

The second movement is one of the most atmospheric jewels of a piece, akin to a Brueghel painting. I can feel myself being rocked gently as the goatherd sleeps, dreaming with a wafting perfume of the meadow flowers – the lolling violin. You can almost see the breeze rippling through the grass as the violins softly undulate in the background, while the viola in a repeated two beat phrase wittily evokes the goatherd’s panting dog – some commentators have even called it a “woof, woof”! It deftly complements the yearning movement of the solo violin, rising and dipping (the secret fantasies of the goatherd maybe?), just as an adoring faithful hound would do.

| Giunt’é la primavera e festosetti La salutan gl’Augei con lieto canto, E i fonti allo spirar de Zeffiretti Con dolce mormorio scorrono intanto:Vengon’ coprendo l’aer di nero amanto E Lampi. E tuoni ad annuntarla eletti Indi tacendo questi, gl’Augelletti, Tornan’ di nuovo al lor canto incantoE quindi sul fiorito ameno prato Al caro mormorio di fronde e piante Dorme’l Caprar col fido can’à latoDi pastoral Zampagna al suon festante Danzan Ninfe e Pastor nel tetto amato Di Primavera all’apparir brillante |

Spring is here! The little birds greet it singing merrily And the streams gurgle away joyfully in the gentle breezesThen the sky is overcast with black clouds, That break into thunder and lightning. In the silence after the storm, Those little birds burst into their merry song again;While, lying in a meadow of sweet-smelling flowers, With the breeze rippling through the grass and the leaves, The goatherd sleeps away With his faithful dog at his side.The festive country bagpipes play away For the lovelorn nymphs and shepherds As they dance under the brilliant spring sky.Tr. by P. Rham |

The key words for the last movement are nymphs and shepherds. Vivaldi cleverly does not fall into the trap of letting rip some bucolic romp to convey the feasting. Instead he creates a restrained, courtly, almost demure, pastoral world as the teasing nymphs and decorous shepherds seem to dance around each other in this season of flirting. The bagpipes are the cellos holding that long bass note that underpins the whole. The end approaches with the crystalline violin evoking the bright fresh light of spring.

And to think that for nearly two centuries most of Vivaldi’s scores lay in oblivion in a Piedmont boarding school run by Silesian monks. It was only a revival of interest in the music of Bach, who himself also suffered from centuries of neglect, that led to a revival for Vivaldi. Bach delighted in Vivaldi’s evolution of the concerto form and honoured him by reworking the Italian’s violin concertos into his harpsichord versions. In 1926, Professor Alberto Gentili of the University of Turin, at the request of the brothers discovered that the whole pile of manuscripts they wanted to sell (97 volumes in all!) were in fact original Vivaldi autograph scores. The very first recording was not until the famous CETRA label’s in 1947. In addition Ezra Pound, believe it or not, sponsored private performances of some concertos in his villa at Rapallo in the 1930s, and there were the first public Vivaldi concerts in Siena in 1939. Who could have foreseen that nowadays the Red Priest’s contest of harmony and invention should almost have become so everyday, indeed almost exasperatingly familiar? The tragedy again is that, as fashions come and go, Vivaldi, too, went out of fashion in his lifetime. He died on July 28, 1741 – as would Mozart some fifty years later – ill and penniless in Vienna, his body unceremoniously dumped in a pauper’s grave. He was 63 years old.

I hope I have convinced you to look again at The Four Seasons as a truly impressive example of Vivaldi’s invention and individual style and to see him as a genuine precursor of romantic programme music and our modern day film music. Hopefully, when you next step into a ‘musak-ed’ lift or curse your luck being put on hold, you will be transported to the goatherd and his dog sleeping in the spring meadows and indeed be reminded of the red priest of Venice with his harmonic invention and impulse. And perhaps you will thank him for filling you with the joys of spring and “wid de boids” you will take wing anew!