“Black and White – a Matter of Principle”: the Artistic Concept of Qin Chong.

May 3, 2022

A Fresh Look at the Limerick: Author Ranjit Bolt Writes for DANTE

May 31, 2022Humans love a good animal story. Across time and cultures we tend to anthropomorphise animals in order to better look at ourselves. But how if those stories were truly told from the animal point of view? What would we see about ourselves then? The image might be quite different to that which we see in the Narcissus Pond we tend to gaze at when telling stories with animal protagonists.

You do not have to think hard to come up with examples of magical flights of the imagination set in the kingdom of the animals. Each country has its own particular beloved animal character: the French have Babar the Elephant; the United States tend to go for well-trained animals like Lassie or Charlie Brown’s pet Snoopy (or is it the other way round?); Australia has Skippy the Kangaroo. But it is Great Britain that takes the biscuit. This is the country where your pet can become a second child; love and devotion are showered on your beloved pooch or moggy or rat or rabbit or tortoise or guinea-pig – you name it, we fall in love with it. Oh, wait, that’s the trap. You see it is not an ‘it’. The animal becomes a ‘he’ or a ‘she’ that speaks and feels, acts and reacts. Welcome to the world of anthropomorphism.

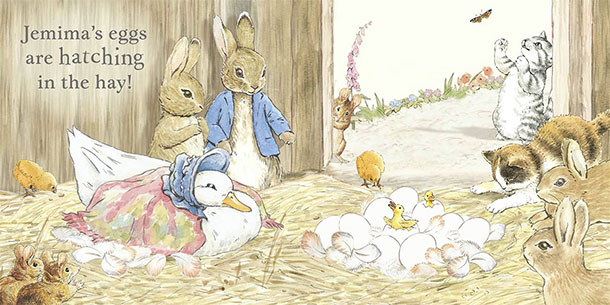

There is the gentle sort as in Beatrix Potter’s delightful evocations of a parallel, childlike, simple world. However, Squirrel Nutkin does not actually represent anything, and Peter Rabbit is just a naughty child stealing lettuces from Mr McGregor’s garden. Many British children and pantomime audiences have also fallen in love with the antics of Toad and Ratty in The Wind in the Willows by Kenneth Grahame. In a more serious vein, Watership Down took us to a world of rabbits pitted against each other, with their own Lapine language, a human odyssey of love and bravery, Hazel and Pipkin’s battle for supremacy against the villainous buck General Woundwort, with all their human flaws and psychology. Exotic weavings from the Raj are to be found in Rudyard Kipling’s magical collection of Jungle Book stories – weird and wonderful explanations for endearing qualities of our Asian jungle friends who take into their care the abandoned Mowgli. Going further back, we have the animal characters of the Fables of Jean de la Fontaine and through him those of Aesop.

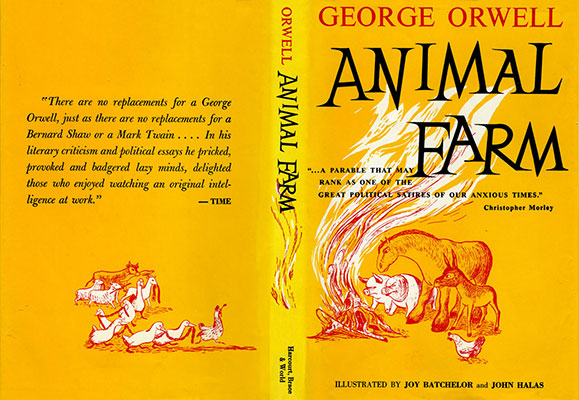

But where are the powerful allegorical stories of redemption and revelation and irony? Here we cannot fail to mention Animal Farm by George Orwell. This is heady stuff – a clinical dissection of the Russian revolution and its aftermath by an English radical who, in the end, hated tyranny of any kind.

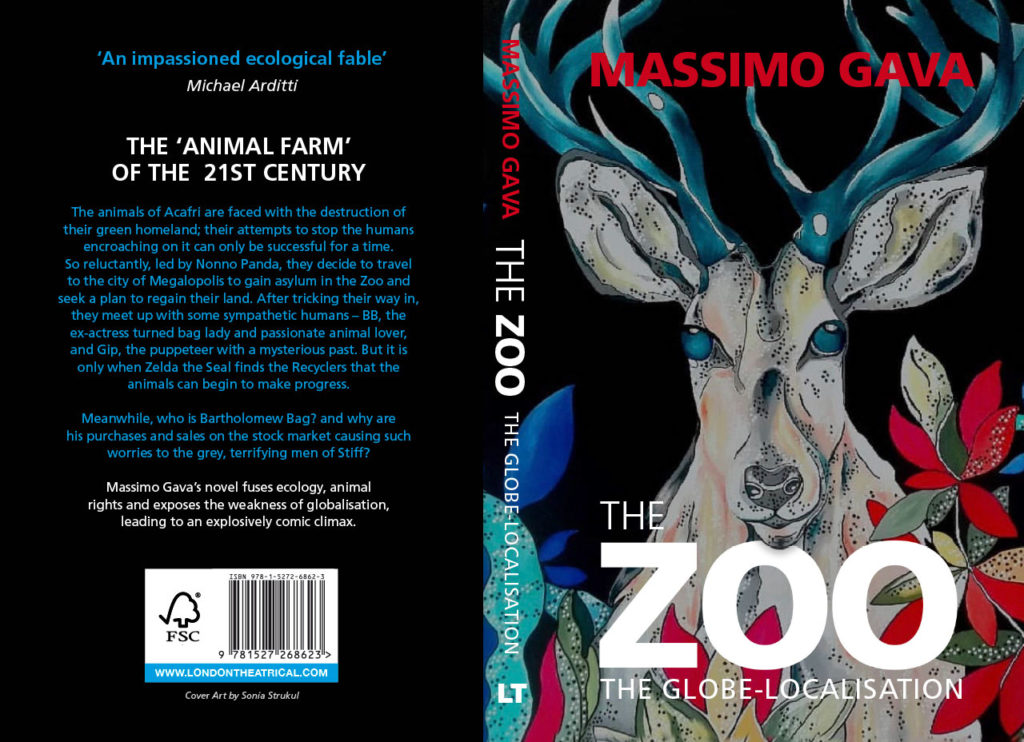

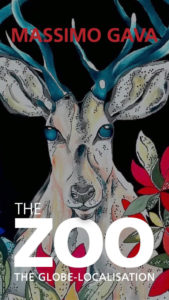

In Orwell’s book, the pigs, Napoleon, Snowball and Squealer, overrun the human Manor Farm, but they gradually become more and more like humans (in fact, in the book, they actually do turn into people by the end), riddled with infighting and paranoia. Inevitably the worthy ideals of the revolution’s beginnings are subverted into specious compromises, aimed at maintaining power, not at liberating the people. This is epitomised by the notorious declaration “All animals are equal but some are more equal than others.” So where can one go if one wishes to avoid a possibly anodyne and saccharine humanisation of the animals we love, while also needing a story with a message – but then again, not one that hits you over the head? It’s a tall order. To fill it, I recommend The Zoo- The globelocalisation , by Massimo Gava.

Published in UK almost ten years ago, it ‘s been now reprinted on papareback by Londontheatrical. The message of The Zoo is clear and up-to-the minute – we must look after each other in this world of ours; we must share it with our animal friends. In essence, we must respect our environment as it is theirs too. On the other hand, unlike Animal Farm, there is no didacticism.

I was utterly charmed by the evocation of an animal world, admittedly somewhat anthropomorphised, but one that views our societal structures and customs from the perspective of the animals. It is a very clever device and throws a spotlight onto some of the absurdities and quirks of our dayto- day existence. At the same time, the world of Acafri, a ‘constitutional animalarchy’, ruled by the benign King Leo, with the Great Councillor Nonno Panda managing to coordinate state responses and delivering enlightenment, mirrors the human world in its structures. But this is leavened with a charming imagination. Thus we have the Chief Bat of the Airforce, the moles from the sappers detachment, a Lupus Rock Band (wolves, of course) and the ‘Miss Goose of the Year’ at the annual Goose convention. As you can story forward and onwards.

The drama is that Acafri has been invaded by the humans with their bulldozers and their encroaching world of concrete and exploitation. Nonno Panda sighs at the realisation: ‘How we have underestimated Man. Fancy imagining that Man would leave us alone and go elsewhere and just bother other Men.’ The animals of Acafri are forced to work together to reclaim their land and their dignity. Gava’s Acafri is a veritable Noah’s Ark. (I should mention the main animal characters are all on the endangered list.) Bats, rattlesnakes, beavers, gorillas, hyenas, foxes, sloths, even duck-billed platypuses, to name but a few, live together and come together to fight the common enemy. As in human society, hierarchies and class differences exist, bickering and infighting bubble up to the surface but Man must be pushed back. He is successfully repulsed but returns with fiercer machines and now a new response is needed from the animals.

Suffice it to say, as they find the overwhelming power of man insuperable they decide to fight from within, become the ‘enemy within’, and exploit the zoo where humans think they are in control. In reality the animals are covertly plotting their revenge. In Gava’s story, interestingly enough, a dissatisfied human who has abandoned the rat race of high-powered multinational financial corporations plots with them, using his computer skills to manipulate events. I will leave you to read the book to find out how the story unfolds!

As I have shown, we have at our disposal a wealth of iconic animal stories and I am sure there exist in every country and continent many more that I have not mentioned. The modern media of film and television have immortalised them but it is clearly animation where the modern world facilitates the bringing to life of these creatures we do so love to humanise.

The Zoo manages to bridge that gap between charm and message and now all that awaits is for the animators to get to work and animate the animals of Acafri. Indeed there are rumours that French Canadian producer Pierre Gendron (producer of the Oscar-nominated Jesus of Montreal, which won the Prize of the Ecumenical Jury at the 1989 Cannes Film Festival and the Genie Award for Best Canadian Film of 1989) is in talks for the rights to turn it into an animated movie with another French producer. So stay tuned. In the meantime read what some actresses and animal activists have commented on twitter and enjoy the reading.

More info on: www.londontheatrical.com

https://www.waterstones.com/book/the-zoo-globe-localisation/massimo-gava//9781527268623

https://www.ebay.co.uk/itm/143752055296