The seven capital sins in modern reality

May 31, 2022

Traveling to Nicaragua is easier than ever

August 4, 2022

The Knock about Comics Jester Logo

It does seem that the sacred is not given much play any more – and good luck to it. Too often notions of the sacred are easily exposed as simply ludicrous – at best – and actually actively sinister – at worst – by the simple expedient of making light of them. Perhaps this is why the powers that be have been so relentless in pursuing the light-hearted (if salacious) productions of an Extraordinary Gentleman and his comics. Massimo Gava writes.

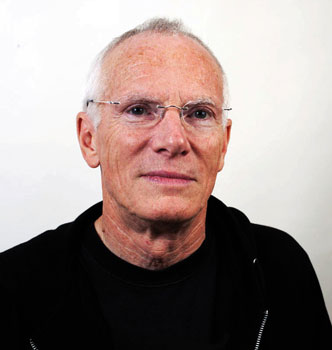

Tony Bennett of Knockabout Comics sipped his tea and smiled, looking back on an extensive career on the fringes of British publishing. “During my long fights against the last gasp of Victorian censorship, I did not foresee the present situation.”

He was referring to the fatwas and violent deaths since Ayatollah Khomeini put a price on Salman Rushdie’s head in 1989. Tony’s battles were played out on the stages of London’s Central Criminal Court and Uxbridge Magistrate’s Court between 1985 and 1996, on either side of the Rushdie Affair and the end of the Cold War.

Tony Bennett

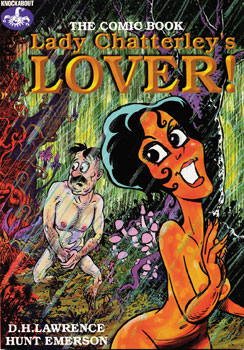

Knockabout fought its cases in the historical tradition of James Joyce’s Ulysses, D.H. Lawrence’s Lady Chatterley’s Lover and the OZ magazine trials. While Rushdie ran for cover and the Berlin wall collapsed, Tim Berners Lee announced the arrival of the World Wide Web. In this context, Knockabout’s trials, under Britain’s Obscene Publications Act and Customs’ import regulations, appeared stranger and more anachronistic than ever.

Lady Chatterley Lover by Hunt Emerson

With the advent of the Web, a vast Pandora’s box of possibilities had sprung open. Computers became the central nervous system of the developed world. However, in spite of the technological advances, our bodies, brains and attitudes retained the shapes and limitations of previous eras. The post-war Western student movement, which promised to herald a new hippie dawn in the 1960s, had long been defeated, ridiculed and fragmented into single-issue pressure groups. Even Punk’s last defiant snarl was turned into a tourist attraction, the anarchist T-shirts and fanzines sold as collectors’ items. Women became ‘totty’. City Boys set the tone, with endless talk of Porsches, bonuses and mortgages. Huey Lewis had caught the mood in his 1986 Yuppie anthem, “It’s Hip to Be Square.” Brash, turbo-charged, predatory capitalism was here to stay, snapping red braces and swilling champagne at Stringfellow’s.

In the following decade, as free market forces surged forward, why did the floundering Conservative government choose to launch a second attack on a miniscule publishing company, with a very limited readership, like Tony Bennett’s Knockabout? Adult comics had never caught on in England. Didn’t the proponents of Reaganomics have other priorities, such as profiting from the uncontrollable feeding frenzy following the wholesale surrender of the City of London to Wall Street? The Black Monday crash of 1987 was partly due to the speed of transactions on the new computer networks. In those early days, half the online searches were by men looking for porn during office hours, so why bother about a tiny, old-fashioned rag distributing Furry Freak Brothers cartoons from Ladbroke Grove? Whose toes had Knockabout’s little jester trodden on this time?

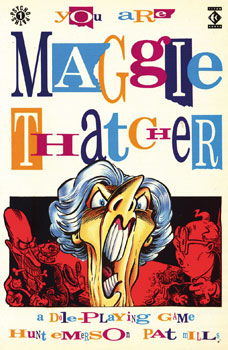

You Are Maggie Thatcher by Hunt Emerson and Pat Mills 1987 Titan Books

The 1985 Old Bailey case had been prosecuted under the Obscene Publications Act by Thatcher’s government. It financially crippled Knockabout. For three years, Bennett’s stock was confiscated and he was effectively out of business. It should have been an easy victory for the government. PEN, the venerable civil liberties organisation, dedicated to “promoting free expression and removing barriers to literature,” did not lift a finger to help. Underground comics referring to sex and drugs were unworthy of PEN’s attention. Bennett decided to raise funds for a judicial appeal independently, with benefit gigs and special events. Against the odds, and at great cost, Knockabout won. Meanwhile, in 1987, Titan Books published “I Am Maggie Thatcher”, an assault on the Iron Lady by Knockabout’s rising artist, Hunt Emerson, scripted by Pat Mills.

Maggie Thatcher by Hunt Emerson

In his 2008 “Now Read This!” review, blogger Win Wiacek wrote, “This powerful piece of graphic propaganda may have dated on some levels but the home truths are still pertinent. Even as Maggie and her devoted pack of lapdogs squirmed on Mills’ and Emerson’s pen points, their legacy of personal gain was supplanting both personal and communal responsibility to become the new norm. Today’s Britain is their fault and this book reminds us of a struggle too few joined and a fight we should have won, but didn’t.” Tony Bennett had defended his corner and had barely saved his business. Then in 1996, the moribund Tories made a last effort to annihilate Knockabout once and for all.

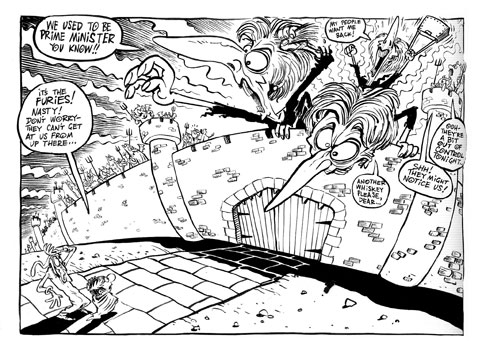

Maggie Thatcher Reappears in Dante´s Inferno as The Furies

This was now ludicrous. After all, the alternative society was a nostalgic memory that posed no threat whatsoever. OZ and The International Times had triumphed in court, but folded due to lack of readership after the oil crisis of the early 1970s. By the 1990s, moral watchdogs began to complain that most of the Internet consisted of porn sites, although they have never risen above 5% of the occupied cyberspace to this day. Dotcom bubbles expanded dangerously. New Labour, in stolen conservative clothes, was converting the ravenous City and its attendant property speculators to Tony Blair’s cause by the thousand. The fresh attack on Knockabout smacked of pettiness and revenge, and was carried out in a suitably underhand way. Eleven years after their Old Bailey defeat, some of 1985’s bad losers were eager to vent their spleen on the same insignificant target again. Despite a new wave of TV comedians deriding a tide of Tory sleaze, something about those little captioned drawings had infuriated them beyond reason.

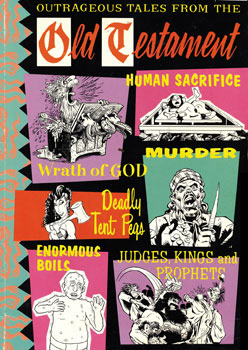

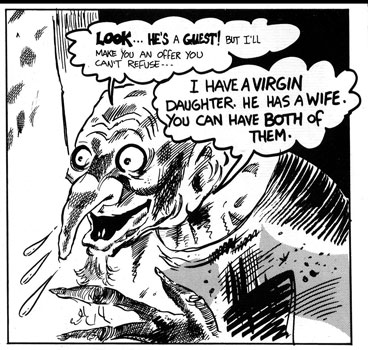

Outrageous Tales From The Old Testament Cover 1987

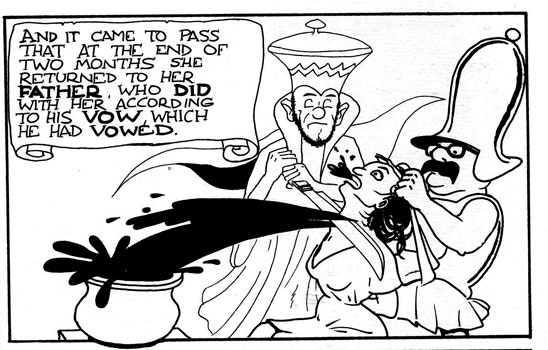

Jephthah’s Daughter by Neil Gaiman and Peter Rigg from Outrageous Tales

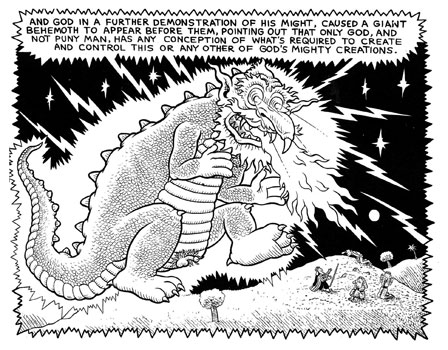

Right-wing Christian fanatics had Knockabout in their sights as well. In 1987, Bennett had published a collection of strips depicting biblical stories. The “Outrageous Tales From The Old Testament” were faithful to their source: full of ancient Hebrew sex, violence and misogyny. The tabloids shrieked, “Would you Adam and Eve it? Filthy Bible!” Hundreds of hostile letters, all with south coast postmarks, came through Knockabout’s door. This was the heartland of the Plymouth Brethren, a strict puritan sect who forbade their children to watch any TV for fear of moral contamination. Tony remembers, “Mary Whitehouse phoned me about that time. She didn’t identify herself, but she had a very distinctive voice. She asked a couple of questions, and when I started to answer them, she hung up.” By 1996, officially retired after a spinal injury, Mrs Whitehouse continued to fret and try to make the 1960s “permissive society” go away until her death in 2001. She probably fumed when Terry Zwigoff’s classic documentary about 1960s veteran illustrator Robert Crumb was broadcast in 1995. And who was about to import copies of Crumb’s “My Troubles With Women”, to cash in on the film’s success? The blasphemous scamps at Knockabout, of course.

Moses by Hunt Emerson from Outrageous Tales

Samson by Graham Higgins from Outrageous Tales

Bennett became aware of a potential threat from customs officials, so he made sure the imported material by Crumb had been declared and approved in advance. However, the 1876 Customs Consolidation Act permitted individual customs officers to seize any material that offended them personally, on the spur of the moment. A certain Officer Martin claimed to have been upset by three panels (out of a total 760) in “My Troubles With Women”, which showed oral sex. Having caused the fuss, he never took the witness stand and Bennett triumphed again.

From The Book of Job by Kim Deitch in Outrageous Tales

So, looking back, was it worth it? Was it anger that sustained our hero while the philistine bigots tried to crush him?

“Yeah,” Tony nods, “I suppose there was some anger, but I won. I got the law changed.”

He remembers a feeling of unreality watching the overpaid, Oxbridge-educated lawyers playing their games of courtroom chess over a few illustrated jokes. Written texts with extremely incendiary ideas are routinely published without opposition. Images, being immediate and easier to digest, even by semi-literate imbeciles, always run into greater trouble.

From The Book Of Judges by Neil Gaiman and Steve Gibson in Outrageous Tales

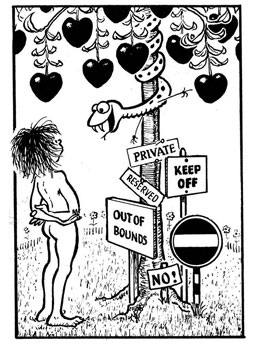

Eve by Donald Rooum from Outrageous Tales

Tony rises to his feet. At 70, he’s preparing to turn himself into one half of a visual joke at a fancy dress party. He needs a jester’s outfit, complete with cap and bells. His girlfriend will ride him piggyback, wearing a nun’s habit. If anybody asks, he has the punch line ready – “Virgin on The Ridiculous”.

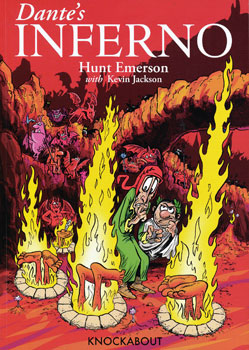

Dante’s Inferno cover

These days, Knockabout no longer distributes, but continues to publish comic books such as last year’s outstanding English version of Winschluss’ “Pinocchio” and, now, Hunt Emerson and Kevin Jackson’s “Dante’s Inferno.” Something tells me we are unlikely to see “Outrageous Tales From The Life Of Muhammad” anytime soon. Instead, let’s have a chuckle at the ideas of St Thomas Aquinas, filtered through Dante Alighieri’s imagination and pushed to their ludicrous conclusion by one of Britain’s great cartoonists, thanks to a publisher who refused to surrender to the eternal forces of darkness and ignorance.

Dante and Virgil by Hunt Emerson