Day of the Faithful Departed in Jujuy, Argentina

October 26, 2022

Christmas – The Cosmic Feast

November 24, 2022By Massimo Gava

All witches and wizards come out to party for Halloween, only to retreat into the darkness of the night and make space for the fragile splendour of a forgotten feast. The day following Halloween is the Feast of All Saints. The name Halloween – now probably best known for Hollywood horror movies, fancy dress parties, carved pumpkins, and associated objects of consumption – derives from the Old English All Hallow Even. That is to say, Halloween is the evening before All Hallows; it is the evening before the feast of All the Saints, which recurs on the 1st of November. The commercialization of Halloween has been very successful, spreading from the USA and the UK to other countries, with a consumer frenzy that is perhaps only second to Christmas Eve. And, like Christmas Eve, in the consumer world, All Saints Eve has lost some of its history, as well as its mystical and liturgical power of reflection.

In Consumerland calendars are primarily useful marketing tools. But calendars are not fixed. The formation of calendars has for centuries been the cause for disputes and the assertion of authority. This is partly because the conception and measurement of time marks significant mores and events; it is also because calendars create a collective memory of one’s place in the grander narrative of time, as well as an understanding of relations with different others. Calendars inform the shaping of common identities. In some countries the 1st of November is still a national holiday. I prefer to call this day the Feast of All Saints and Sinners, because in every human being there is a capacity for both luminous holiness and the darkness of sin. So, this is also a feast for celebrating the fragile splendour of being human.

Saints are usually understood as people who have died, but in the Christian tradition angels are included among the saints. An astonishing portrait of angels and saints, standing alongside Richard II, known as the Wilton Diptych, gives an illustration of the import and beauty of saints in the collective imagination of the misnamed ‘dark’ Middle Ages.

Wilton Diptych: Virgin and Child with Angels, 1395 Tempera and gold on panel, ca. 37 x 27 cm. National Gallery, London

This anonymous work of art is part of the National Gallery collection in London, which is a must-see for any visitor, and is free of charge to the public. The feast of All Saints is not concerned with the well known royal saints standing behind St. John the Baptist and Richard II; the 1st of November celebrates all the unnamed blue angels that surround the Virgin Mary and the infant Christ Jesus. In other words the 1st of November is a feast for all non-celebrities. If we are now living in a culture that is obsessed by celebrities, then this feast is thoroughly counter-cultural because it celebrates the ordinariness of the extraordinary potential of being human.

The feast of All Saints is a very egalitarian feast because, with its institution, the Christian Church sought to celebrate all the lesser known saints; that is to say, this feast celebrates all the holy people and angels that are not remembered in other days of the liturgical calendar. Let me clarify: in Christian calendars each day of the year has traditionally been a feast-day for particular named saints. Feast-days may have become universally accepted (such as the feast of Saint Michael the archangel, on the 29th of September), or may vary according to time and place. Saints differ also according to their Christian denominations. An obvious example of the latter are the Protestant English martyrs who are not included in the Roman Catholic calendar of saints, and vice-versa; a legacy of the bloody English Reformation and Counter-Reformation under the rules of Elizabeth and Mary Tudor.

Later on, towards the end of November occurs the feast of a female saint who was for centuries widely celebrated throughout Europe, but has now been largely forgotten. In the western Christian calendar, the 25th of November is the feast-day of Saint Catherine of Alexandria. The story of Catherine of Alexandria – of Catherine’s wheel fame – may have been consigned to popular oblivium, partly because she has often been confused with another saint, Catherine of Siena. This other Catherine is and was a veritable celebrity, recently endowed by the Vatican with the honorific titles of Doctor of the Church and Matron of Italy. In her lifetime, in fourteenth-century Italy, Catherine of Siena was already considered a living saint; songs and poems came to be written in her honour. She left numerous writings and had many followers. Similarly to Lady Gaga and Mother Theresa of Calcutta, her many fans called her mamma; for them she was a loving and authoritative mother. It is therefore possible that Catherine of Alexandria may have been overshadowed by the superstar status of this later Italian saint.

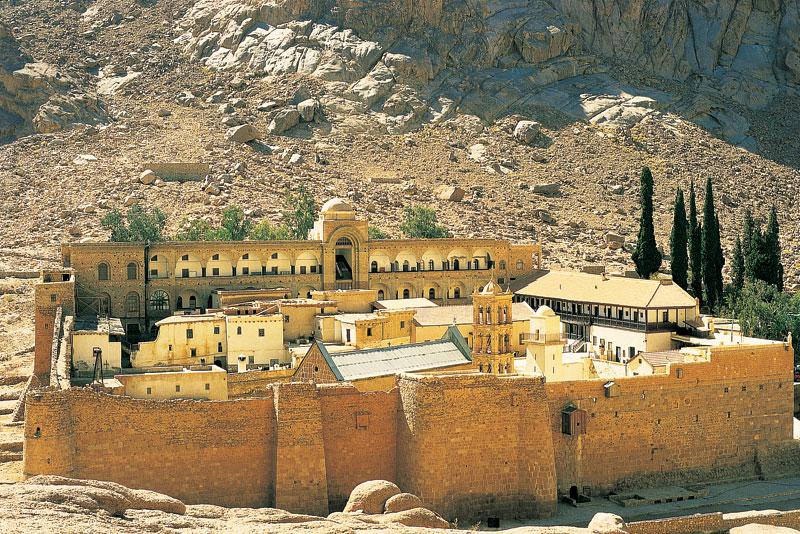

Perhaps more disturbingly, Catherine of Alexandria was removed from the official calendar of western saints during a great ‘historical’ purge, on the basis of lack of historical evidence for her existence. Roman Catholic scholars reached this decision on the basis of agreed historical methods; yet it seems theologically unsound if not outright ludicrous for Christianity to appeal to historical evidence as a source of belief. The story of Catherine of Alexandria is worth recalling and retaining for a number of reasons. Firstly, because her name is remembered in many geographical places, as well as early churches and monasteries. The following examples testify to her widespread fame, across deserts, cities, and valleys. In the Egyptian Sinai desert, one finds the Orthodox monastery of St. Catherine, which is said to preserve some of her relics.

The Church of Santa Caterina d’Alessandria, dominates Piazza S. Caterina in the Italian city of Pisa, not far from the well-known leaning tower. Santa Caterina is now a diocesan church, but in the Middle Ages it was a centre of learning and preaching for the Dominican Order, endowed with a magnificent library, with the presence of friars who were among the first to translate and write in the vernacular, often at the bequest of women.

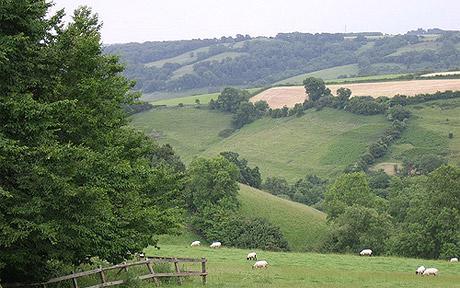

Meanwhile, in the bucolic English valley of St. Catherine, stands as a medieval jewel the little church of St. Catherine of Alexandria, originally built by the Benedictine monks of Bath Abbey and now part of the Diocese of Bath and Wells.

Secondly, because of the tragedy of a recent historical film entitled Katherine of Alexandria.1 This is indeed a tragic film, not because of the tragic end of Catherine, but because it is generally badly acted, and scripted even worse, with very little resemblance to the medieval stories of her life. A medieval tale of a woman’s learning and courage is turned by this film into a tale of sex and power. Catherine, who in the medieval stories is a woman of royal lineage who converts with her teaching and preaching, is turned by the film into a destitute nomadic girl, who is brought up by the a lustful emperor and becomes the unwilling seed of military rebellion against unjust political power. Likewise, the famous wheel that, in the medieval stories and paintings represents Catherine’s power through prayer, is turned by the film into the instrument of a quasi crucifixion. This film shows one of dangers of forgetting that new myths often replace old stories. And myths are not just fairy tales, they inform our reflection on what it is to be human.

Thirdly, and perhaps more importantly, Catherine of Alexandria was extremely popular in medieval Europe, especially among Christian women, for whom she provided a model of the learned and strong-willed holy woman who had studied, travelled, disputed philosophy, and preached. Across European libraries there are numerous manuscripts and early books containing her hagiography; i.e. the story of her life, written in Latin and in the vernacular languages. There are some variations between hagiographies, largely depending on where they were written, on their languages, their commissioners, and their intended audience. The most widespread is probably the Golden Legend written by the Dominican friar Jacobus da Voragine. Sermons were preached on her feast-day, when the feasts involved not only religious services, but also food and music, often provided by the wealthy for the poorer members of society. Images of Catherine of Alexandria, with her iconic wheel, have been portrayed for centuries through painting, stained glass, and sculpture. For instance, Fra Angelico painted her alongside many other female saints for an altarpiece that can now be found in the Museum of San Marco, in Florence. Saint Catherine of Alexandria is the first woman on the right hand side, recognizable by her crown and her wheel. Near her, Fra Angelico portrayed many other holy women, some of whom remain anonymous to us; so the feast of All Saints is for those forgotten women, too.

Fra Angelico, The Lamentation, 1436-1441 Tempera and gold on panel, 109 x 166 cm. Museo di San Marco, Florence

On these November feast-days, taking their lead from medieval people, wealthy people may wish to provide for those who are poorer than themselves. If one is in London, one may wish to view the German gilded sculpture of Saint Catherine of Alexandria at the Victoria and Albert Museum – also free to the public – and recall that women in Christianity have not always been portrayed as meek and obedient to authority, they have also shown great strength of will and great learning.

The story of Catherine’s life may seem extraordinary to some, but the lives of the saints are full of what may be perceived as unconventional. For instance, it was not altogether exceptional for early female saints to dress as men, sometimes in order to enter and study in a male monastery. So, the lives of the saints provide some of the earliest records for cross-dressing and the fluidity of gender roles. But that’s another story.

On the day after Halloween, the forgotten feast of All Saints, Christian counter-culture admires the creativity of human beings who have sought to celebrate the wonders of God’s creation, especially those who have come and gone before them. It is a feast for remembering all the non-celebrities whom, in the ordinary extraordinariness of their lives, have enabled pieces of heaven to become visible, to be felt and heard here on earth, in an attempt to join in the wondrous task which is the fragile splendour of forgotten feasts – such is the fragile splendour of human love.

People are also interested in reading The Zoo. The Globe-Localisation.

https://www.ebay.co.uk/itm/143752055296.

https://www.waterstones.com/book/the-zoo-globe-localisation/massimo-gava//9781527268623