On the Slow Train to Somewhere

August 15, 2022

All Saints and Sinners: The Fragile Splendour Of Forgotten Feasts

October 29, 2022Mexico, has perhaps the most famous Day of the Dead celebrations. But similar syncretic traditions and remembrances can be found in other countries in Latin America, where pre-Columbian rites have mixed with Catholic overlays. Indigenous Andean traditions for The Day of the Faithful Departed are – despite the homogenising encroachments of North American Halloween traditions – still strong in the Andean provinces of Argentina, and especially in Jujuy – Argentina’s northwesternmost province, bordering Chile and Bolivia.

The commemoration of the dead has very deep roots in Andean culture in our province of Jujuy, Argentina. In common with the rest of Latin America, we commemorate the dead in accordance with traditions which evolved from combining our forefathers’ ancient practices with the Christian religious rituals that were inherited from the missionaries during our continent’s period of colonisation.

The day when we pay our respects to the departed souls is November 2 or, as it is known, “The Day of The Faithful Departed” – November 1 being, of course, All Saints Day in the Catholic calendar.

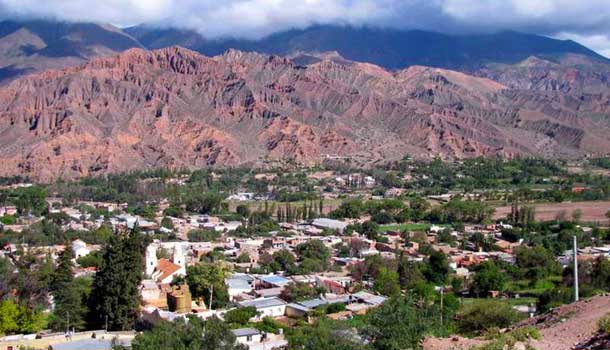

Puna highlands in the Province of Jujuy

The story goes that during this ceremony God is supposed to open the gates of heaven and the departed descend to earth to visit their loved ones. In return, their family and friends welcome them with all the things they loved when they were alive. The belief is that they stay with us on earth from midday on November 1 until midday the following day. Different rituals are performed over the course of these two days. It is a time, above all, when people experience simultaneous emotions of joy and sadness. Essentially, it is for families who have lost a loved one and is continued for three years following the death. With the passing of each year, however, the preparations become less elaborate and the ceremony less solemn.

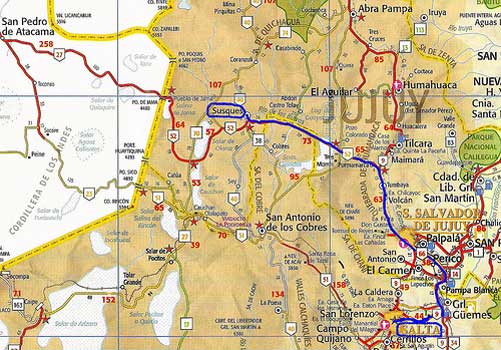

Map of Susques

The ritual begins on October 31 when the family gets together to prepare the favorite foods of departed loved one. Bread dough is kneaded and rolled out into all kinds of shapes and forms – ladders for the departed soul to climb down from heaven; doves (to transport them back); and angels, wreaths, crosses and animal figures. In addition, families make wreaths out of paper flowers because in our regions of Puna and Quebrada de Humahuaca fresh flowers are hard to come by. We call all these objects we make our “offerings.”

Humahuaca: Holy site

If you go to any market in these regions of Argentina, you’ll find on sale an assortment of these bread offerings, paper flower wreaths together with the so-called tocoris (onion flowers), candles, and not forgetting the local drink chicha, made from fermented maize or manioc. In fact, you’ll find everything you need for the ceremonies.

Humahuaca: Holy site

On the day of November 1 itself, the family sets up a table in a large room in the house, where the offerings are spread out. This is the Offerings Table. In the middle there is a layer of fresh flowers; a bowl of holy water where the visiting souls can leave their blessing; and dishes filled with traditional sweetmeats, pochidos (basically, popcorn) – all this food and fruit, of course, is for the benefit and pleasure of the departed spirit. Naturally you mustn’t forget to provide wine and chicha and finally coca leaves! If the deceased was over 18, we lay the offerings out on a black table cloth. But if he or she was a child, then a white cloth is used. Pride of Family and friends sit around and reminisce about the dead person, chatting about him or her while drinking coffee, wine or chicha and smoking and “coking” (coqueando) – that is, chewing on coca leaves.

Susques Cemetery

Family and friends sit around and reminisce about the dead person, chatting about him or her while drinking coffee, wine or chicha and smoking and “coking” (coqueando) – that is, chewing on coca leaves.

Market at the entrance to the cemetery in Tilcara..

People believe the spirits spend the whole night eating and drinking, so the family stays to keep them company until dawn breaks. In some houses, they sing a little song:

“On the day I die Two candles I’ll burn One to die well The other not to return”

Commemoration Homemade bread.

As mentioned, this ceremony takes place each year for three years after the person’s death. In the first year, the overriding feeling naturally is dismay and respect as the memory of the departed is still so raw. In the second, it’s more about being comforted, the departed souls are stronger and that means the family gathering can be more fun, with people telling anecdotes, stories and riddles. In the third and last year, the ceremony involves the final sending-off of the soul, which has an original stamp to it. On the morning of November 2, the family gathers at the cemetery, carrying onion flowers, paper flower wreaths, and some offerings to adorn the grave. After midday, all the food the departed loved one didn’t manage to eat is shared out between the relatives and friends in a true act of communion.

Food for the celebration of the departed

In this day and age the commercial world bombards us relentlessly with North American Halloween traditions that have nothing to do with our own. Our children – and indeed some adults – put on costumes and roam the streets “trick-or-treating.” As responsible adults, we must defend our heritage by ensuring these ceremonies and rituals are handed down to our children. Without a shadow of a doubt, they represent one of the most authentic expressions of our popular culture, combining as they do, Catholic tradition, naturally, but also those ancient rites the original peoples of Latin America practised and believed in.

Translated by Philip Rham

People are also interested in reading The Zoo. The Globe-Localisation,

https://www.ebay.co.uk/itm/143752055296

https://www.waterstones.com/book/the-zoo-globe-localisation/massimo-gava//9781527268623