The Choice – The New Michael Arditti’s Book

June 1, 2023The word Halloween is first attested in the 16th century. It represents a Scottish variant of the fuller All Hallows Even, the night before All Hallows (or All Saints) Day.

By Massimo Gava

Photos: Vittorio Celotti

The practice of dressing up in costume dates back to the Middle Ages. Trick-or-treating resembles the late medieval practice of “souling”, when poor folk would go door to door on Hallowmas (November 1), receiving food in return for prayers for the dead on All Souls Day.

Although the Irish and British tradition was transplanted to America, few know that it dates back to the Roman feast of Pomona, the goddess of fruits and seeds, and to the festival of family ancestors, Parentalia. This tradition was kept intact for centuries in Italy. Even Shakespeare mentions the practice in his comedy The Two Gentlemen of Verona in 1593, when Speed accuses his master of “puling like a beggar at Hallowmas.”

The memory of my living relatives obviously doesn’t extend back to 1600, but they still talk about the traditions of the Italian folks at the end of the 19th century, with yearly festivals leading up to All Saints Day and carrying on for the rest of the winter.

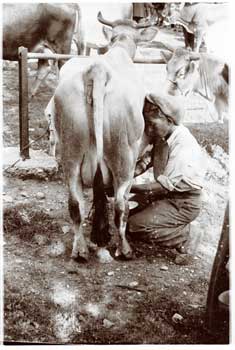

A lot of those people were illiterate. Going to school was expensive and that took needed labour away from the land. They lived in a ruthless world where the struggle to survive was a daily battle. They fought the fatigue and despair of endless labour with whatever means they could.

Some sort of escape from these harsh realities was necessary. So these people became masters in the art of overcoming fatigue, learning to guess when they did not know, and using their imaginations to create what they did not have.

Winters were cold and long. After 4 p.m., darkness fell like a blanket of ink and stayed for sixteen hours—an eternity. The kitchen had just enough firewood to cook, so when the meal was finished and the fires began to fade, all the families living around the courtyard moved to the stable.

It was the only warm place thanks to the presence of the animals, and that’s where the magic theatre of the Filò began.

The story of the Filò was information, remembrance, communication, but above all, a fantastic training ground for creativity. It was born into a sad and poor world, devoted to sublimation and fantasy, aiming for redemption, survival and hope.

In today’s society, full of overweight people, it is difficult to imagine the hunger of that time. Thanks to the fantastic tales in those stables, the night felt not so cold and that food for the mind anaesthetized, at least temporarily, the needs of the body.

The Filò traditions date back to the 1500’s. Ruzzante, the Venetian writer, mentions this practice in his comedies. The primacy of these traditions is seen also in the rest of the Veneto, Friuli, Lombardy, Tuscany, Emilia Romagna, Abruzzi and Sicily. An endless amount of diverse agricultural knowledge, rites, cuisine, songs, and fairy tales were handed down orally from generation to generation.

In each family there was at least one guardian of this precious knowledge, but most of it was entrusted to a special person with a real talent for storytelling.

They were often lonely men, sensitive visionaries, with a past full of experience. In exchange for a place to sleep and some food, they offered their craft during the day and their narrative talent at night.

In simple words, they told the stories of what they witnessed in their travels, terrible diseases, epic wars, cataclysms, exorcism of devils, and ghosts.

The narration of those events evoked images that illuminated the night for the community. In their own minds, they all made their own films. People moved from one stable to another choosing the best performance. It was open to all.

An oil lamp was the only illumination. In that dim light, words took on special textures beyond the short, luminous perimeter of its glow. In the shadow, the noises of the animals, their scratching, their munching, added a soundtrack to the tales. The sounds of the audience carrying on with their tasks offered a counterpoint—the beating of the weaving loom that made rough hemp sheets, the flip-flop of the flask that children used to turn cream into butter, the rustle of the corlo spinning the wool. The wool, shorn from sheep and goats, was made into everything from shirts to gloves and socks. The sounds of this important activity gave the Filò its name—it means “hand spinning”. In the warm and humid stables, humans co-existed harmoniously with the animals on which they depended, in a very delicate balance.

Men and women, discreetly separated as in church, worked as they listened to the tales of the old. The boys, sitting in respectful silence, won over the girls with furtive smiles. The girls, lowering their eyes, kept working on their canvas embroidery, so they could conceal their real feelings, certain their blushes were obscured by the half-light. But up among the rafters of the stable, it was all a fluttering of the wings of rutting Cupids.

Children clung to grandparents with their eyes and mouths open, lost in the magic of stories of the Filò, while outside the fog with its tentacles entrapped the rest of the world in its net.

On All Saints Eve, the different regions celebrated their traditions’ rites. In Sicily, they prepared gifts and cakes for the children and told them that they came from people that had passed away. In Emilia Romagna, the poor went from door to door asking for food in exchange for praying for the dead. In the Veneto and Friuli, hollowed-out pumpkins were painted and turned into lanterns, the candle in it signifying the resurrection.

It is fascinating to see how these traditions have evolved over the years to such a degree that very little remains of the festival of Samhain (summer end) from Celtic times.

The current imagery of Halloween is derived from many sources encompassing national costumes, works of gothic and horror literature, and classic films. But still the old traditions come back full circle, returning perhaps with a different meaning.

Consumer society re-adapted the old ways and concepts to suit their purposes, just as immigrants to America carved the pumpkins instead of the original turnips, accidentally recalling the Italian tradition.

The world is constantly evolving – for good or for bad, who can say which? Maybe another full circle is about to be accomplished in a world and way of life that is increasingly unsustainable. An alternative Filò could be just around the corner for future generations – scary, don’t you think?

Consider it as my Halloween trick!

People are also interested in reading The Zoo. The Globe-Localisation.

https://www.ebay.co.uk/itm/143752055296

https://www.waterstones.com/book/the-zoo-globe-localisation/massimo-gava//9781527268623