With a history of political chaos, military oppression, economic turmoil, disease and natural disasters, Haiti, poorest country in the Western Hemisphere, seems mired in misery. An estimated 300,000 people perished in the catastrophic quake of January 12, 2010. which measured 7.2 on the Richter scale. Here in the land of Voudou, the real and the surreal meet and are often indistinguishable. But the small beginnings of hope and healing can also be found amidst the rubble. Liane Thompson recounts both the horror and the humanity she found there.

I

It was January 2010 and I was in mourning, crying tears over the death of my life. My marriage had collapsed. I was devastated, and angry: at my ex for his abuses and infidelities, and at myself for not leaving him. A child of divorce myself, the fear of passing divorce-related trauma on to my children kept me from destroying our home, so I stayed and became a shell of a person.

My 23-year old daughter Tia finally asked me, “Mom, are you going to wait til you’re 60 to leave him?’” My answer was “No!’ but I had no plan. Then my dear friend Chris, who had recently passed through the dark tunnel of divorce himself, suggested, “Why not go to Haiti? The Israelis are sending aid. You could go with them and cover the earthquake.”

His idea made sense. As a video journalist, I had covered world events before, and I had to admit, work was exactly what I needed. I had a destination now, but still no plan for getting from Israel (where we had relocated to be near my ex’s mother, a Holocaust survivor) and Haiti. I made a few calls and a humanitarian group agreed to take me along if I paid my own way. I had no idea from where I would get the money, but I told them to book my ticket anyway.

My mind was racing. Where would I get the needed cash? Then out of the blue, I got a phone call from Miriam, a fellow American, who had spoken of her divorce during our first meeting months before. Immediately I told her my situation and how desperate I was to go to Haiti. Putting me on hold, Miriam phoned a diamond dealer friend who she thought might support my escape.

She got quickly back on the line. “OK, I just spoke to Daniel and he’ll give you the money. Consider it a mitzvah,” said Miriam.

“Really? But I’m not Jewish.” I replied.

“No worries, neither are the Haitians,” laughed Miriam.

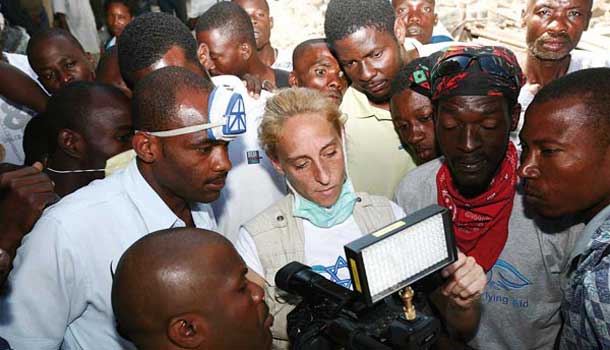

With Daniel’s help I was soon flying to Haiti. The seats and aisles of the plane were filled with rescue workers from around the globe. Relief workers from Italy, Ireland, France and Israel gathered to discuss their latest disaster experiences and anticipate the catastrophe ahead. I was embedded with Israeli Flying Aid (IFA), a relief organization founded and directed by Gal Lousky, an experienced humanitarian. For the past 15 years, Lousky has travelled the globe bringing relief to victims of natural disasters and war zones. In Haiti, she planned to provide shelter, food and medical assistance to the country’s orphans.

We landed in Santo Domingo in the Dominican Republic and travelled from there to Haiti. It was dark when our three-vehicle convoy finally hit the outskirts of Port-au-Prince after a dangerous ten-hour drive. The IFA volunteers I travelled with were trained medical clowns from Dream Doctors – soulful specialists dedicating their lives to easing pain. They’d joined IFA to help the children of Haiti cope psychologically with the catastrophe they’d experienced. I would spend much of my journey filming Hamutal Ende, one of the medical clowns, with whom I shared a tent. The two other clowns that volunteered had worked disasters before, but Haiti was the first time out for Hamutal, and a challenging place to go green.

We drove to the Israeli Defence Forces’ Home Front Command field hospital which would be our temporary base camp until we hooked up with an orphanage to work with. The impressive, MASH-like compound specialised in children, women in labour and the elderly. Security directed our three-van convoy through the complex and we stopped near the mess hall where prayers were underway. It was Friday evening and Sabbat dinner was just beginning. But instead of going inside, I grabbed my camera and followed Dudi Barashi, one of the medical clowns already walking toward the patient tents.

Inside a pediatric tent, small children with various earthquake-related injuries were resting in cots; Dudi went to work very quietly. Chimes from his music box filled the room replacing cries from the cast-clad children. Bubbles floated through the air bringing smiles to the faces of those kept awake from discomfort or fear. A grateful look appeared in the eyes of the few parents that sat nearby as they watched Dudi’s clown magic work miracles.

Dudi’s clown magic work miracles.

We had managed to escape the worst of the immediate aftermath, arriving days after rescue teams had already saved those they could and cleared away most they could not. By then, the stench of death had replaced cries for life; survivors gathered near collapsed buildings chanting, dancing and wailing, lamenting for family members who remained buried beneath the rubble.

Jocelyn, our Haitian guide, had come from the countryside to Port-au-Prince in search of work. He knew one of the many rescue teams or humanitarian organisations would need a translator and Jocelyn spoke fluent English, Spanish, French and the local language, Creole. He was focused, assertive and smart, the kind of guy that got things done even in helter-skelter Haiti. Yet Jocelyn always stopped to help others as if on his own mission.

On the afternoon of January 12th, Jocelyn was driving his scooter to work, having just kissed his wife and small daughter goodbye, when fierce trembling caused him to spin out of control. The bike crashed to the ground and Jocelyn hit the pavement head first. Dizzy and disoriented, Jocelyn returned to his house to find it completely demolished, his wife and child dead inside. Jocelyn drove his scooter, now his only possession, to Port-au-Prince and ended up at the IDF field hospital the night we arrived. Initially, he didn’t speak about his loss or the pain he was surely suffering. In fact, in the days that followed, Jocelyn worked non-stop, with a smile, as if the quake had spared him from personal tragedy.

Jocelyn led the IFA volunteers through the capital in search of an orphanage to repair. Scores of earthquake victims lay on the pavement under sun protection tarpaulins in makeshift clinics on the city streets. Our red-nosed, happy-faced clowns ducked under the barrier tape and headed toward the children. I followed, filming as they sang and administered their own form of medication: a dose of humour. Clown treatment worked wonders as many of the quake victims, young and old responded with smiles. Soon every medical facility in Port-au-Prince wanted their own set of Dream Doctor clowns.

IFA volunteers entertain the children and staff

at the Orphanage of Our Glorious Saviour

The nuns of The Orphanage of Our Glorious Saviour, a Catholic orphanage that housed thirty girls before the calamity, were suspicious when we arrived at dusk later that day. A week before the quake, “relatives” had taken four older girls away for a family visit, but they’d never returned. The nuns suspected that the girls were taken as slaves, a serious problem that existed in Haiti before and grew extensively after the earthquake. Gal told the nuns we wanted to help the orphanage, and we had no plans to take any child anywhere. Then we saw Samira.

Three-year old Samira was severely malnourished and looked only one. None of the children had eaten in days. They were starving, like many of the 8.7 million Haitians. Before we arrived, the nuns were even considering sending the girls away, thinking their chance of survival was better on the street. Samira looked as if she were on the verge of death and needed to go to hospital straight away, but the still-cautious nuns objected. Only after Gal warned that Samira might not survive the night, did the nuns agree, insisting that one of the sisters accompany the child.

When we arrived at the IDF field hospital, the paediatrician wanted to send Samira to the US Naval Ship Comfort, a Navy hospital ship anchored off the coast of Haiti, but Gal refused. She had promised the nuns she would look after the child. After much debate, the paediatrician acceded; for almost the entire night Gal sat cot-side, holding Samira’s tiny hand.

Samira remained at the field hospital for days recuperating, while Gal, Hamutal and others from the IFA group returned to the orphanage bringing food, mattresses, blankets, and more, compliments of the IDF medical team and Israel Orange, the cellular company financing Gal’s IFA endeavour in Haiti. Since the quake, the children had been sleeping across the street on the ground outside, even though the orphanage was intact. They were too afraid – like most Haitians – to sleep indoors, fearing another earthquake. Gal had a plan: acquire the empty lot adjacent to the orphanage, clear away the debris, and construct a large wooden structure in which all the girls could sleep peacefully. A concrete wall would protect the girls from strangers and the street. With so many Haitians starving, crime was escalating and Gal wanted to make certain the orphans, and the six-month supply of food she just bought, would be safe. In typical Israeli fashion, a security guard was enlisted.

We were driving to the market to buy construction supplies and recruit workers when Jocelyn, Ariel and I heard a dreadful scream. Ariel looked back and saw a young woman fall to the ground. Immediately, Jocelyn slammed on the breaks and we all jumped out. Twenty-two year old Milan was lying on the pavement, blood gushing out her leg. Seconds before, a man had approached Milan asking for money. When she refused, he hacked her with a machete, hitting a main artery.

Milan on the way to hospital

Quickly, we put Milan in the van and headed to the closest hospital, one operated by the Americans. Milan wavered in and out of consciousness on the drive and when we arrived she barely had a pulse. Entering the emergency tent, I broke into med-speak: “Twenty-two year old female, penetrating trauma, machete to the leg, possible femoral artery damage, unresponsive for about three minutes.” The doctors immediately went to work, looking peculiarly at me as I recited Milan’s information as I filmed. When one of the physicians asked me to put away the camera, the surgeon in command responded, “It’s OK, I know her, she’s from Trauma: Life in the ER.” I glanced up and recognised him from a hospital once featured on the show.

Thanks to my many years producing Trauma, a medical reality series, I pretty much had carte blanche at the University of Miami’s airport field hospital, where doctors and nurses, who loved the hit show, allowed me complete access. I reconnected with old acquaintances. Being recognised as a competent person was like getting a shot of dopamine. I was starting to feel like my old strong self again.

Later that night, while smoking a cigarette outside the orphanage walls, Jocelyn and I heard drums beating in the distance. We followed the sound which led us to some fifty Haitians wearing long robes, walking in a circle, chanting with arms stretched out high. Jocelyn said they were praying and thanking God for the earthquake; they believed God had caused such devastation in order to turn the world’s eyes on Haiti. Global attention, along with international aid, was his way of offering the locals a chance at a better future. (It is true that the international community would pledge some $5.3 billion to help Haiti, but almost two years after the quake, the country remains a shambles, still plagued with poverty, corruption and disease.) I interviewed the head priest who told me to hold onto my soul. Then he gave us a brief tour of his destroyed worship hall. Afterward, Jocelyn and I walked back to the orphanage; the worshippers followed us, single file, whispering the entire way. For the first time since arriving in Haiti, I felt danger, not from the people themselves, but rather from spirits in the air.

God’s-Planet Ministries was run by Grant Rimback, a Tennessee welder turned preacher who managed an orphanage of 150 children on the outskirts of Port-au-Prince. By the second day after the quake, Grant had converted his old bread truck to haul victims. It became one of the few “ambulances” on the road saving lives. For days, Grant drove non-stop without sleep, taking survivors to any location able to offer care. As the foreign medical teams arrived pitching tent hospitals, Grant and his rescue rides, complete with a comforting southern drawl, were known to all. He truly was a saint.

I spent the next three days with Grant transporting victims between hospitals and clinics, and taking the lucky ones home. By day, we drove throughout the countryside, mostly where rescue workers had not yet been. One afternoon, we went to Mt. Cabrit, or Goat Mountain, to view the amazingly beautiful valley below, and the tent city growing in the distance. At the rock mine on the mountain top, the earthquake had caused an avalanche of gravel burying seven workers, one inside his tractor, without a trace.

The next day was Sunday, the Lord’s day of rest, which meant a God’s-Planet sermon was on the morning agenda. I crawled out of my tent to the soft sound of hymns echoing from the orphanage church a few yards away. I grabbed my camera and entered the still intact building just in time to film Grant asking “our Lord Jesus Christ” to help heal the victims of the quake. Then the choir rose to praise God, swaying and singing glorious songs of unconditional love. I cried.

Laughter shortly followed, as Jocelyn, Ariel, and Hamutal, clad in her clown apparel, arrived with fun, games and teddy bears for all Grant’s children. Again, Gal brought joy, and moreover, she had also organized a truck-load of food for the orphans of God’s-Planet. We escorted Grant to GOAL, the Irish humanitarian organization donating the food, and said goodbye. Then Jocelyn, Ariel, Hamutal and I returned to the Orphanage of Our Glorious Saviour.

The place had changed in the few days I was away. A fence separated the yard from the street in the neighboring field, where a large wooden tent structure stood instead of debris. Inside, mattresses covered the floor and balloons hung from the plastic ceiling, in preparation for the good-bye party soon to follow. The water tank had been replenished and the sewage removed from the outhouse. In the main hall, boxes of medical supplies were stacked next to the Bibles, and an IDF physician examined the girls while nurses administered vaccinations nearby. A generator, provided by one of Grant’s visiting missionary groups, supplied electricity. Not only had the place changed, but the girls had changed too; in their eyes there was hope and even happiness.

The next day the IFA group would be leaving Haiti and the sisters had splurged on an evening meal of rice with pork. After dinner, I said goodbye to Jocelyn, our guide, and we wept. For the first time, he talked to me about the death of his wife and daughter and how, if it weren’t for work, he would’ve collapsed long ago. He hated to see us go, knowing the pain from his loss could no longer be avoided. I made him promise to get help, treatment for PTSD. I told Jocelyn my own story and the events that had brought me to Haiti. Jocelyn and I hugged tightly, as if accepting all that remained was the memory of our lost family.

When I returned home after ten days away, I opened the door to a babysitter. I spent the next four days alone with my children, processing my trip via my script. Late one night, I swore I heard a female voice singing a Haitian song. I thought of Milan, wondering about her fate, and about the priest, and holding onto my soul. When my ex returned, I insisted he move out.

Then my brother called from California, wanting to hear all about my Haitian adventure. Chris once served as a church music director, but now he provided internet concerts and had been giving morale-boosting performances for the crew aboard the USNS Comfort, the hospital ship anchored off the coast of Haiti. I told him about my trip and when I mentioned Milan, Chris shrieked, “Hey, I know about the lady hacked by a machete. A nurse from the ship told me they brought her in.” He continued, “She almost died. You saved her life.” Recalling all my post-earthquake experiences in the Voudou nation, I replied, “Haiti saved my life.”