Why Issues Matter More Than Leaders

March 16, 2018

Of Men and Angels. Arditti’s Epic Tale Spans Centuries

March 22, 2018The Man Who Shot the World: Unseen Duffy Photos Define an Era

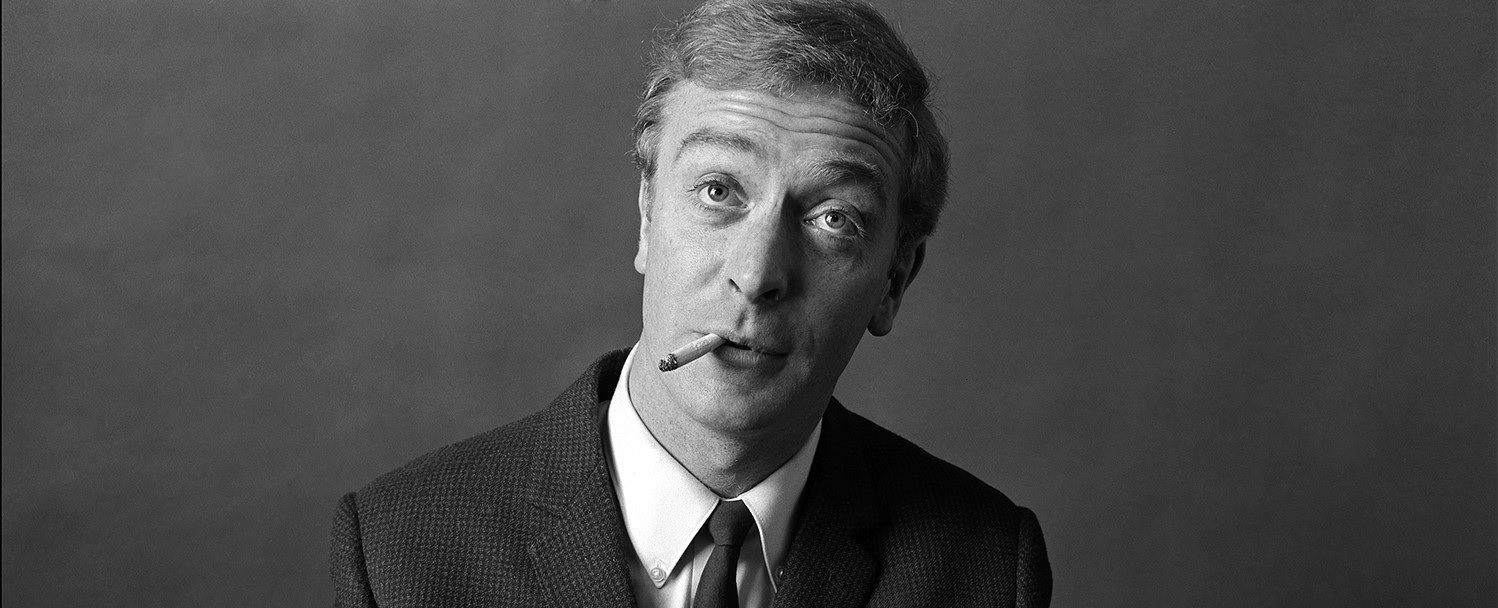

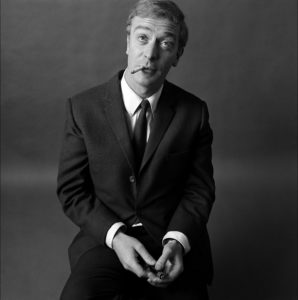

Michael Caine Smoking, 1964 Photo Duffy © Duffy

Mark Beech talks with Chris Duffy, both about rare photos, reproduced here and in a London exhibition, and other shots that are mega-famous. They all sum up the 1960s and beyond.

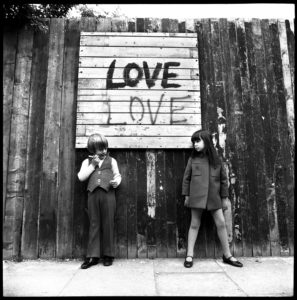

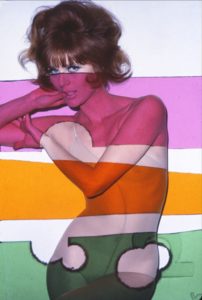

Love, Queen Magazine, 1968

Photo Duffy © Duffy Archive

Great photography defined: You just need the right look, the right subject, in the right place at the right time.

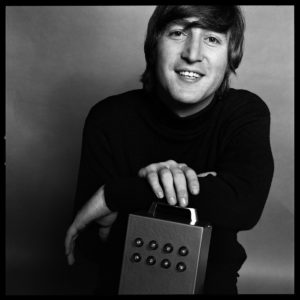

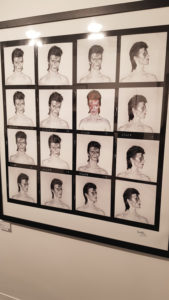

The exact moment when the shutter clicks to capture the essence of the subject. John Lennon, just back in London from Shea Stadium, fooling with a gimmicky box sold to him as a “UFO Detector.” Michael Caine, relaxed and off guard, cigarette dangling from his lip. David Bowie, in best Aladdin Sane mode, his eyes both closed and then open to show the famously permanently-dilated left pupil.

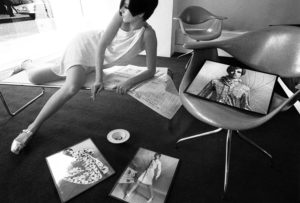

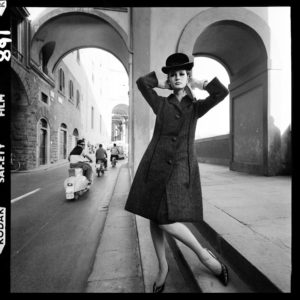

The critical point where the photographer captures the whole soul of the model, a moment in time, and simultaneously sums up a whole decade of style, such as the swinging 1960s London. Model Jean Shrimpton, looking wide-eyed, cool and impossibly innocent all at once. Jane Birkin, captured at the exact “moment critique” in mid-jump, almost floating in the air. Paulene Stone, smouldering into the camera, her modesty protected by strategically-placed coloured plastic gels. Endless photos of models, shot not as if they are clothes horses but as if they actually own the outfits. They sport Vidal Sassoon haircuts and miniskirts on the King’s Road, and then appear so poised in Florence that the Vespa riders are almost falling off their scooters looking at them.

Jean Shrimpton, Studio Photograph, 1963 Photo Duffy © Duffy Archive

All this and more is in the stellar portfolio of the late Brian Duffy, or Duffy as he is generally known. He had the name long before the musicians Duffy, or Steven “Tin Tin” Duffy.

Duffy’s work is being showcased in a major retrospective at London’s Proud Gallery near Charing Cross. There are also books available showing some of his finest works.

They fit in well with the new Michael Caine documentary, My Generation. Caine and Duffy were good friends.

“There’s great interest in the 1960s as the start of pop culture,” says Duffy’s son Chris, a photographer himself. “We had an opportunity to get some of Duffy’s 1960s work out. The Duffy Archive has been involved heavily with the David Bowie Is exhibition since 2013. It is refreshing to go back and look at some of his other work.”

John Lennon with UFO Detector, 1965

Photo Duffy © Duffy Archive

Duffy is often put together with Terence Donovan and David Bailey as “the terrible trio,” or “the black trinity” as Norman Parkinson called them. They broke all the rules and hobnobbed with celebs. They were celebs themselves. Duffy might have surpassed them all if he had not quit the business to become a furniture restorer.

It is not too much to say that Duffy shot some of the most famous images of all time. Such as the Bowie album covers. Aladdin Sane, with lighting-flash makeup. Lodger, with a weird accident victim. Scary Monsters has a weird Pierrot clown. Duffy once said that Bowie was “just a guy who liked dressing up”, while Lennon was “like any nice, normal, intelligent person”.

Yet, his best work is arguably away from the famous faces, such as in some of the rare or previously unseen but eye-catching images featured here.

“Duffy wasn’t just known as a rock photographer but he happens to have taken some of the most iconic images,” adds Chris. “There is a lot of really interesting material but it is good to have a jewel in the crown.”

Duffy originally studied dress design at St. Martin’s School of Art because that was the subject chosen by many pretty girls. After a few failed jobs he worked as a commercial photographer and in 1959 shot his first commission for The Sunday Times. Soon he was working for Elle, Vogue, Town, Queen and other magazines. He took the debut shots of Shrimpton staring longingly into an Edgware Road shop, like an English breakfast at Tiffany’s. Then he pictured her for a Kellogg’s advert. He introduced her to Bailey, joking “she’s too posh for you.” The rest is history.

Jane Birkin, Floating Queen, 1965

Photo Duffy © Duffy Archive

Among images in the Proud Gallery show are those of the very first Jaguar E-type convertible on the newly-opened M1. Duffy often escaped the studio and even Paris or London to seek provincial backgrounds which nobody else dared to use.

Among his other subjects, one may find the hard stare of writer William Burroughs; the pout of Brigitte Bardot; the sparring gangster Reggie Kray; naked Christine Keeler and Grace Coddington; and Harold Wilson looking Prime Ministerial.

French Elle gave him the most freedom. A 1977 fashion shoot takes three top models beautifully made up, and almost hides their faces behind a tree. Rival lensman Helmut Newton called Duffy to say that this anarchistic shot was the best thing he had seen in a long time.

Duffy’s later commercial work was hugely influential, such as a surreal series for Benson and Hedges with cigarette packs turning into caged birds and pyramids. A series for Smirnoff vodka was ground-breaking. “Well, they said anything could happen,” ran the slogan as a submarine comes up in a Los Angeles swimming pool and a drinking skydiver wears a swimsuit and flippers. The last was shot at an airfield in north Yorkshire with a 40-foot drop and no safety net – all long before Photoshop was thought of.

Paulene Stone, Colour Gels, Town Magazine, 1963

Photo Duffy © Duffy Archive

“Those images were shot on his favourite camera which was part self-constructed out of different cameras with 6X9 Mamiya backs, a great format,” says Chris, who also noted Duffy came out with the Silk Cut concept adverts (minimalist white and purple silk) which he sold to Paul Arden at the Saatchi ad agency.

“Even so the pressure was building for some time. He despised himself for doing so much advertising, because, being a hugely intelligent and articulate person, he felt that personally he was way more ahead of the game than some of the people he was working with. A lot of them were fairly talentless and he was just prostituting himself,” Chris says. In 1979 Duffy abruptly retired: “He had got to a point where there was less and less money in photography and he was having to support his system of two assistants and a secretary and running the whole show.”

Duffy’s last session was in 1980, says his son: “At that point he had converted his studio into his restoration space. He was interested in Georgian furniture and liked working with wood and was very adept at making bits and pieces. When David asked him to shoot Scary Monsters they used my studio. I had assisted from 1973 to 1979 and I did so again.”

Then came the famous ‘bonfire of the transparencies’. Chris notes: “Duffy came into work one day. An assistant told him, ‘We’ve run out of toilet paper.’ That was the straw that broke the camel’s back. He just snapped and grabbed packets of negs and prints and set a bonfire with them in the garden.”’

Queen, Kings Road, 1968

Photo Duffy © Duffy Archive

Bailey happened to call in and tried to stop the destruction, offering: “I’ll look after them for you if you want.” Duffy said, “Don’t bother,” and continued to burn them.

The present writer first spoke to Chris in 2011 and about two months later I interviewed Bailey, who once said “Duffy and aggravation go together like gin and tonic.” Which is a little rich, since Bailey enjoys provoking people himself. Bailey claimed that most of those works burned were second-rate, commercial works. Chris respectfully disagrees. “I think he was just grabbing what he could arbitrarily. I don’t think he went through it and thought what was good or bad. You can tell in the archive there are big chunks which have completely disappeared. You might have job 1,000 and there is nothing until 1,200. For example, Duffy was good friends with John Lennon and he photographed him several times but we have only got one session in the archive. Things still come up. We just had The Observer call to ask if they could use a picture and I had never seen it before.” More material has emerged on eBay, Pinterest, libraries or in the back files of magazines: “I do have these moments of sleepless nights when I think, ‘God what have we not got,’ because Duffy was shooting for 20 years day and night – many thousands of pictures.

Ponte Vecchio Florence, 1962

Photo Duffy © Duffy Archive

“Luckily, trying to burn negatives is a bit like trying to burn old phone books – they are so dense and burn very slowly around the edges and exude a black horrible acrid smoke, so that slowed him down a bit. Neighbours complained and a council guy came and looked over the fence and said, ‘hey, you can’t do that.’ It stopped him destroying everything, which was to our benefit years later. When I started the archive I asked Duffy if he regretted doing that and he did. But he was a great believer in you had to burn your bridges to move forwards, so that was in his head at the time. He had had it with photography. So it was onwards and upwards, get rid of the old and clean out the cupboards, get rid of this stuff which is just hanging around as junk. Of course, time changes everything and all that material has become massively valuable and people look back on it now in a new era of evaluating work as art. Interest in photography is just unprecedented.”

In 2004, Duffy was diagnosed with a degenerative lung disease, pulmonary fibrosis. In 2010, he died at the age of 76, leaving behind a small number of signed works, many on view within this London exhibition.

One hopes more of Duffy’s photos will resurface, but even as it stands it is a remarkable body of work. Chris Duffy concludes: “Duffy was commissioned by various clients to go out and shoot the pictures. He never put on his smock and beret and said he would be an artist and create something amazing, it was just another commission. I suppose, like anything, cream rises to the top. If you think of music, there are thousands of bands that can play three chords but all these years later, we see just the Ramones and the Pistols and the Clash – all the good stuff stays and the other stuff disappears.”

E-Type Jaguar, Opening of the M1 Motorway, 1960

Photo Duffy © Duffy Archive

- Sixties Style: Shot by Duffy is at Proud Central 32 John Adam Street London WC2N 6BP through March 18. Images courtesy of Proud Galleries, Photo Duffy © Duffy Archive Available books include Duffy by Chris Duffy. Mark Beech’s All You Need Is Rock includes an earlier interview with Chris Duffy.

https://www.proudonline.co.uk/exhibitions

https://www.duffyphotographer.com/store/

Michael Caine Smoking, 1964

Photo Duffy © Duffy Archive

Gallery scene with bottle (Mark Beech)

Gallery scene with Ziggy (Mark Beech)