The Age of Protest: World Revolution in the Making?

July 1, 2012

Food for thought

July 1, 2012Why Photography Matters As Art As Never Before

Courtesy of Alejandro Chaskielberg, Oxfam and Michael Happen Gallery Portrait of Napva Kaanvang and Losike. Kangwira collecting water for local women. Turkana Series 2011

Photography in the age of Photoshop can be manipulated, staged, denatured and rareified. It can also reveal truth, humanity, and even love. Rodrigo Cañete argues that the latter is the power and the potential of the medium as an art form. He walks us through the contemporary photography landscape, leading us to the raw humanity, strength and dignity of Kenyan villagers as seen through the lens of Argentine photographer Alejandro Chaskielberg. It is there that photography brings us face to face with the L-word.

Courtesy of Alejandro Chaskielberg,

Oxfam and Michael Happen Gallery

Portrait of Napva Kaanvang and Losike.

Kangwira collecting water for local women.

Turkana Series 2011

A

A truism of our time is that ours is a visual culture. The reality, though, is that very few people are interested in images and almost nobody really looks. The potential of the image is curtailed in our society and its ambiguity denied, probably, as dangerous. Ours is a time that does not trust the ambiguous, that which is in-between. It eradicates doubt in two ways: science or faith. It is ironic that both modes of thought depend on the sense of sight to exist.

Courtesy of Alejandro Chaskielberg,

Oxfam and Michael Happen Gallery.

Portrait of Tioko Korima.

Turkana Series, 2011

The Baroque Era is a Catholic affirmation of the need to see in order to believe. Contemporary art is heir to this belief, even in its more abstract and disembodied forms such as minimalism, where the visual still brings certainty by clarifying what an object is and what it is not. The most serious debates of contemporary art are concerned with the visual as a source of certainty. The paradigmatic position is that of Michael Fried, who stabilised the meaning of the minimalist work of art (of practitioners such as Donald Judd, Carl Andre, Dan Flavin, Sol Lewitt) by stating that it is art (and not just an object) as far as it is theatrical or, in other words, as far as it is exhibited to an “art public” that sees it as “Art.” Rather disappointingly, Fried seemed to lift us up high only to drop us, generating more questions than answers. For him, if the meaning of a work of art is not understood, it is because it has run out of meaning, and that is the end of the matter. Born and raised a Catholic, I have, and have had, art around me all my life. Art has always given me that sense of “home away from home,” standards for beauty, and a sense of continuity when things got too shaky. Michael Fried approaches contemporary art without taking into consideration the L-word when discussing its nature. I agree with his opinion, however, that the relevant debates in contemporary art are happening in the realm of photography. Thomas Demand or Thomas Struth are, according to Fried, quintiessential Art because they transform a picture that should, by definition, be small and mnemonic into something large enough to deserve the attention of the “Art viewer.” Fried focusses on a few German photographers whose works are not only theatrical (because the “Art viewer” points at it as Art in the context of the museum or gallery) but also transform that theatricality into their subject matter. Thomas Demand’s photographs of bland sights of urban (office) life are images of a lie because what looks like the real thing is actually made of paper. So, far from being an agent of certainty, photography reveals itself as another weapon of manipulation. In Thomas Struth’s case, images of ‘Art viewers’ viewing Art in museums and churches prove that although the art looked at is real, the viewers are extras. This is definitely interesting but it is also exclusive because that information is not currency. This elitism is also characteristic of the other members of what is known as the Dusseldorf School, which also includes mega-stars Candida Hopfer, Thomas Ruff and Andreas Gursky. Their photographs are lavish, colourful and sleek. Having said that, the concept behind them is repeated to exhaustion without any sign of innovation. Their success was such that people paid millions for a Gursky even when they knew that the c-print would eventually lose its colour and disappear. This art is not for ever, but ephemeral. As sleek and chic as they are, I cannot help but think that behind these ironic visualisations of the limits of their media, there lies nothing. If Art is what the Dusseldorf School claims it to be, it can only be an ironic visualisation of the limits that the medium imposes on it. But as much as I am trying to agree with Fried and these Germans, put art in a box and close this discussion for good. I feel that art is more than an intellectual exercise. To begin with, as Bruno Latour recently said, art is a vehicle of people through time and space. It conveys presence. There is something personal in art that can only be understood on a one-to-one basis. This is why Roger Fry said that the era of the museums killed that personal relationship between the viewer and the work of art. Now, millions gather in front of Velazquez’ Las Meninas in the Museo del Prado, to give one example, without having a clue as to what is going on in the painting or of its real meaning. Yet they seem to find certainty in the idea that, just by being in the same room and looking at the image, some value will be added to their lives. The personal experience happens between the two actors (viewer and work of art) that are present. Far from being an intellectual experience, it is one that happens and is relevant in the context of the viewer’s life. The idea that seeing the divine (the authentic and essential) live and in person comes from Jesus’ lifetime, when holiness was transmitted through sight. That is why those who were in the same room with Jesus were considered ART Courtesy of Alejandro Chaskielberg, Oxfam and Michael Happen Gallery. Portrait of Tioko Korima. Turkana Series, 2011 DANTEmagn.5 17 holy and as were later, in Spain, the mystics who saw him in their flights of the soul. Museums are, in a way, spaces that contain the essential (pieces that are unique and authentic and convey some kind of truth) – very much like churches in the past. The pilgrimage to art fairs and museums all around the world reinforce this argument. But is the world becoming more cultured? If not, what makes art so special?

Courtesy of Alejandro Chaskielberg,

Oxfam and Michael Happen Gallery.

Portrait of Frederic Ekuman

Turkana Series 2011

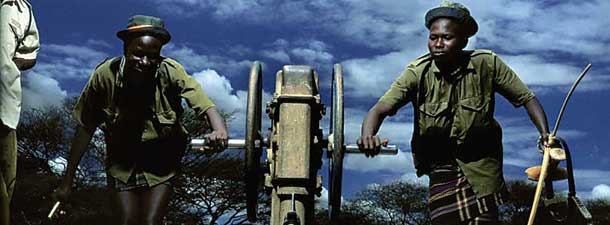

Photography, understood as art, has been focused either on stylisation or on the descriptive as reportage or as story telling. The Dusseldorf School, however, is neither stylised nor descriptive but addresses specific problems that art faces as art. The problem with the latter is that it is too cold. I totally understand their commercial (and academic) success because they produced the image as justification. They instantaneously make the one who deals in and with them serious and believable. They are art that looks like art. But that superficiality of sorts always ends up taking its toll. I am saying this because the aforementioned German photographers exclude the human figure, turning the pictures into mere academic exercises. Recently there has been a photographer who has recently taken me out of that sense of Middle European depression. Alejandro Chaskielberg is showing his latest works at the Oxo Gallery in London. Sponsored by Oxfam, his project aims to show the extreme natural conditions in which Kenyan villagers live. The result is a group of pictures that, in my opinion, helps redefine the role of photography as a human art form, not just an academic exercise. The images seem to be painted with light in hues that never go too far away from green and red. Chaskielberg explains: “I’ve always been attracted to the night. So in Turkana, [Kenya], I explored the idea of photographing people during the night, often in the places where they sleep. To photograph people, I used the full moon, along with long time exposures and different kinds of lights, like torches. I only had a very short window to get the shots I wanted, no repeats. It was a real challenge!” In spite of those short windows of natural light, Chaskielberg’s Tarkana comes across as warm and dignified – something that he started to explore in a work from his previous series, Mr.Whiskers. Chaskielberg avoids turning the exotic into the other. His sitters exude comfort. It is through the use of light and colour that he achieves that sense of “home.” Through a combination of dark dominant reds and greens and a white light that caresses them, the images of the subject are rendered totally clearly, but the sitter is still allowed to conceal certain things. The photographed space is like a womb. Chaskielberg seems to follow Caravaggio’s chiaroscuro, where the vertical light enhances volume and expression, while at the same time it reveals a series of figures that seem to come out of the darkness into the viewer’s space. His portraits of villagers Rebecca Eporon, Elizabeth Ekatapahn, Lokesiro Natelem Eseron and Joseph Ichom are dignified without reaching the level of monumentalisation of Mr.Whiskers, who can never be taken seriously.

The picture that takes all these issues to a new level is a group portrait of kids surrounding Frederic Ekuman during a break from digging for water at the roadside of Kanka, Lungurio. Since the Renaissance, the work of art has been mainly conceived as a window into a different world. Photography in particular has been conceived by the intervention of the camera that, in a way, penetrates the fabric of the world and opens that window with total accuracy. Thus the act of viewing has always been initiated in the viewer and from him or her into the image. Here, Chaskielberg opens a very baroque window, not to look, but to be looked at. The composition emulates Byzantine icons in which the flatness is more due to the fact that they are hovering over the viewer because the space that matters is the viewer’s, not the subjects. The issue of the space of the viewer as the valuable one – the one towards which the kids move – transforms the image’s composition into an allegory of migration which overlaps the already delicate symbolic force of their African selves.

If the reader did not have the opportunity to see the image, his guilt would be post-colonial and geopolitical – the “UNICEF approach” where the kids seem to beg for mercy. Chaskielberg, by contrast, does not patronise them but seems to oblige the reader to follow him when flexing his knees and levelling the eye contact. The kids do not look upward, but frontally. They move forward and appear playful and curious. Thus, their frontality is reassuring and sweet. Oxfam should be proud of having partnered with Chaskielberg for this project because he has redefined the way inequality should be portrayed in order to achieve maximum efficiency: by making his ART Courtesy of Alejandro Chaskielberg, Oxfam and Michael Happen Gallery. Portrait of Frederic Ekuman Turkana Series 2011 DANTEmagn.5 18 ART subjects equal to the viewer. From this viewpoint, common sense suggests that in order to see the differences we must see the similarities. The photographer masterfully manages to alter this inequality through the same enhancement of the texture of the silky darkish skin by use of a vertical light. As in Caravaggio, this light reveals primary colours that transform warmth into heat and makes the viewer smile. By lowering the camera to the eye-level of the children, he balances the inequality that has always existed in the representation of African kids in the past. Thus, viewer and children are confronted without sentimentalism nor accusations of any sort. Without a humanistic rhetoric (a la Henry Moore) or a visual slogan (a la Sebastiao Salgado), the group portrait is not humane but human. He reveals the grace inherent in characters that do not know inequality as such. Baldassare Castiglione in Il Cortegiano (ca.1520s) defined grace as follows: “…e per dir forse una nuova parola, usar in ogni cosa una certa sprezzatura, che nasconda l’arte e dimostri ciò che si fa e dice venir fatto senza fatica e quasi senza pensarvi. Da questo credo io che derivi assai la grazia.” (. . . and maybe say a new word, use in everything a certain nonchalance that hides the art, and let what you do and say be done without effort and almost without thinking. I think that comes from this very grace). This calculated nonchalance adds up to the grace of these characters who are not flattered but just treated as equals and given the benefit of the doubt. The reader should notice at this point the difference between Chaskielberg’s treatment of Africa and Afrikaans South African star Pieter Hugo, who is represented by genius photography dealer, Israeli-born, New York-based Yossi Milo. Pieter Hugo’s approach to his sitters is mediated by a beige veil that conveys dirt and draught. Hugo conditions the moment of viewing from the very beginning while Chaskielberg makes them as equal to us as possible. It makes sense, for equality is the precondition of friendship, and we can only help those who we love.

Courtesy of Alejandro Chaskielberg Oxfam

and Michael Happen Gallery.

Portrait of Naniti Alkaram

Turkana Series 2011

From a theoretical point of view, Chaskielberg’s image is so engaging that it does not need to boast academic status. By rejecting that status, he speaks a visual language that will not include him in quintiessentially theatrical art spaces such as Tate Modern. For the Argentine, art should be experiential, not self-referential. It is at this point that we should ask ourselves what makes a work of art. Is it the way it looks (let’s call this one the “decorative” approach)? Is it the way it questions the limits of its medium (this is the “art about art’ approach)? Or is it the way it changes the world at a human level (the work of art as a vehicle of presence)? Any answer to these questions will only speak of the speaker and will be conditioned by our experiences and failures. I would dare, however, to say that there are two extremes that would frame the myriad possible responses. On the right, we have those who think that art should look like art and question its own existence as a medium from an academic perspective. According to this view, taste is always exclusive to those who know what looks like art and what doesn’t. To the left, the opposite view would say that art is a visual representation whose presence affects the viewer – a kind of space where the presence of the artist is felt in the viewer’s space, skin or body at a phenomenological level. This entails a dialogue person to person, present or not.

Courtesy of Alejandro Chaskielberg Oxfam

and Michael Happen Gallery.

Portrait of Naniti Alkaram

Turkana Series 2011

Alejandro Chaskielberg’s images move us without sentimentalism. I remember my shock when I first saw his first series La Creciente. Those images of the Estuary of the Rio de la Plata spoke to me at a very personal level. They took me to my nights of insecurity about the future and my life which, paradoxically, was the happiest time of my life. I used to sail down there. Without having met, we had done so. The sheer power of presence Courtesy of Alejandro Chaskielberg Oxfam and Michael Happen Gallery. Portrait of Naniti Alkaram Turkana Series 2011 Courtesy of Alejandro Chaskielberg, Oxfam and Michael Happen Gallery. Group Portrait of Mary Atabo and her family in Kaalatum. Turkana Series 2011 DANTEmagn.5 19 that even the landscapes had in that exhibition made me go back to what were both the happiest and scariest days of my life. He had captured something essential, of course, to me and manipulated it in a way that allowed me to revisit my past. This series made him a deserving winner of the Sony World Photography Award (the equivalent of the Oscars in photography). I was curious, however, about his next series and expectations were high. The acclaim he received could have easily inebriated him and he could have started to produce the sort of Argentine images that have infested our imagery for the past fifteen years, a colourful mix of kitsch, pop, and raw silliness that demands a very specific type of art market, and excludes seriousness ex ante. Knowing that his is a gift, he rose to the challenge and transformed photography into a form where the artist is present even when absent.

Courtesy of Alejandro Chaskielberg Oxfam

and Michael Happen Gallery.

Portrait of Naniti Alkaram

Turkana Series 2011

The key image of his Turkana show is, in my opinion, the one called Dreaming Family, a shot of Elizabeth Ekatapahn and her family sleeping outside on the ground on a hot night. It is a tour-de- force because, like in Bernini’s Apollo and Daphne (at the Borghese Palace) where the viewer discovers the story with each step taken around the sculpture, it is kinetic. There is a different temporality and that is the temporality of the (longtime) exposure of the camara in the darkness of the night. It works like Marina Abramovic’s performances where the conditions for something real happen. Marina lectures the viewer through example and irony. Alejandro creates a space in the viewer’s mind where the performance occurs. He evokes a dream that Elisabeth had and what we are seeing is not only the sitter having the dream, while sleeping on the dusty soil under a Joshuashaped tree, but also the dream itself. Not only that dream is revealed by the lens. We can see the artist at work, very much as in Velazquez’s Las Meninas. It is a disembodied self-portrait, although it is difficult to say disembodied because we can actually see the footprints on the floor of someone (surely the artist) weaving with mirrors that mosaic of moonlight that generates these miracles. At the level of the metaphysical, the phenomenological, the procedural this picture is almost a theological statement of work, empathy, and what makes us human. Love, actually.

Rodrigo Cañete is a Courtauldian academic, art dealer and blogger