COP21 | United Nations Paris conference on climate change

November 30, 2015

Spring Awakening or What Makes Gery Dance?

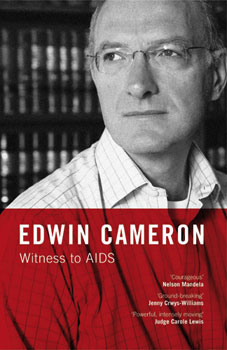

December 1, 2015Edwin Cameron is a senior judge in South Africa’s Supreme Court of Appeal and the only person in public office to acknowledge having HIV/AIDS. In his book Witness to AIDS he gives a frank account of his own experiences with the condition, the political denial surrounding HIV/AIDS, and the struggle that millions in South Africa and the rest of the continent face getting treatment. Cameron is the 2009-10 winner of Yale University’s Brudner Prize and lives in Johannesburg. He speaks to Massimo Gava.

MG: You’ve said that you’re the only official person who’s come clean about living with AIDS in South Africa. Since making that statement and the publication of your book, have you seen any changes in the perception that people have of the AIDS situation?

EC:

Eleven years since my public statement on AIDS, there has been immense progress in understanding the disease and in combating stigma. But, puzzlingly, very few or no public figures in Africa speak openly about their HIV status. In South Africa, this was partly due to President Mbeki’s flirtation with AIDS denialism – which put a profound chill on sensible and open discussion of any sort. But outside South Africa there is also a telling absence of political leaders willing to speak about themselves as living with HIV, even though we know they do exist. That difficulty continues to be due, I think, to the fact that HIV is sexually transmitted.

MG: In your book you write ‘The primary reason HIV/AIDS drugs were inaccessible to the developing world was because of the prices imposed by the manufacturers.’ To what extent have the political classes lost touch with reality, allowing companies to profit from the same people that elected them?

EC:

There may be profit in drugs, but there is still strength in activism. The history of the AIDS epidemic shows vividly what principled, well-focused activism can achieve angry, outspoken, well-informed activism. In 1997 when I started on anti-retrovirals, the drugs were unaffordable to all but the wealthiest one per cent of Africans. Now, nearly one million people in my own country are receiving ARV treatment free through the public health sector. That is a brilliant success. Drug costs have become only a relatively small component of saving lives in the AIDS epidemic. The most important problems are healthcare infrastructure and political leadership. But as to cost, that battle has largely been won.

Edwin Cameron – senior judge in South Africa’s Supreme Court of Appeal

MG: Is there a law in South Africa that prosecutes people who knowingly infect others with HIV?

EC:

I have long fought against criminal laws that specifically target HIV sufferers. That’s because they increase the stigma, and although they’re supposed to be aimed at protecting women, they’re often applied against them. In South Africa we successfully resisted an HIV-specific criminal law. One of our strongest arguments is that ordinary criminal law is effective enough to deal with a case where someone, who knows he has HIV, deliberately passes it on to another.

MG: Were religious groups partly responsible for the AIDS epidemic in Africa?

EC:

Religious dogma has played an abject and negative role in the epidemic in Africa, especially when some groups opposed the use of condoms and persecuted gay men. Gay men are a particularly vulnerable group.

MG: You’ve said ‘A rank colonial legacy of racial thinking and bigotry has plagued our understanding of AIDS in Africa.’ How would you describe the current situation?

EC:

Fortunately, since President Thabo Mbeki left office towards the end of 2007, officially-sanctioned AIDS denialism has gone. The new health minister, Aaron Motsoaledi – a doctor with a hands-on experience of rural poverty – is forthright, committed and determined. And the man who toppled Mbeki, President Zuma, has been speaking with telling candour about the disease. The bogeys of the Mbeki era are gone. And none too soon! Now we can talk frankly about HIV as something that’s sexually transmitted – a precondition to tackling stigma and discrimination, and getting people into treatment programmes.

MG: In your book you claim ‘Racial oppression and racial subordination are a legacy the white settlement of Africa created and it is one that all South Africans are struggling to eradicate. Pretending it is not there is our least acceptable option.’ In your opinion what should be done to change this situation?

EC:

The legacy of racism is slowly receding. Already more than half of South Africa’s middle class (52%) is black African. However, disparities do remain. There is a residue of white racist practices and most importantly wealth remains skewed: South Africa is one of the world’s most unequal countries. My own view is that constitutionalism – that is the rule of law, separation of powers, and an enforceable bill of rights – offers the best road to prosperity and human dignity, particularly since the South African Bill of Rights includes enforceable socio-economic rights. This means that government is under a progressive duty to provide everyone with the minimal means of survival, and that the courts can oversee how government performs this duty. Countries in Africa where the rule of law has failed, including South Africa’s neighbours, Zimbabwe and Swaziland, offer dismal portents of what may happen over here if our constitutional project does not succeed.

MG: You write, ‘I am not a virologist, not a demographer, not a sociologist, not an epidemiologist, not even – except to the extent that legal practice and judicial duties necessitate it – a student of human character. But I give my view.’ What is your general view on the current state of South Africa?

EC:

I am worried, worried about the terrific levels of crime, worried about increasingly brazen corruption, and worried about economic growth and inequality. However, I remain cautiously optimistic. I think South Africa has enough hardworking and skilled people, many of whom are extremely dedicated, to grow into a successfully functioning and economically flourishing democracy.

MG: Do you think the gap between the rich and the poor has narrowed in the 18 years since the end of apartheid?

EC:

There are more black Africans than white members of the middle class. But the gap between the rich and the poor has grown since democracy. To put it differently, the wealth disparity in South Africa has become more of a class than a racial issue. Poverty has been largely de-racialised. That removes one problem, but leaves the major problem for us to deal with now, namely poverty and inequality.

MG: How do you hold together a nation like South Africa with eleven official languages and 52 ethnic groups?

EC:

Under apartheid, South Africa’s extraordinary diversity – differences of colour, race, ethnicity, language, sexual orientation, culture – were a reason for oppression and injustice. Under the democratic constitution, our differences are a source of celebration and strength.

MG: South Africa went through one of the most peaceful revolutions in human history, yet it’s a nation that has one of the highest crime records in the world. What should be done to keep it under control?

EC:

A number of things will help us deal effectively with crime. One would be a well-trained, efficient, uncorrupted and responsive police force, which we do not have. Another would be a national culture that denounces criminals, particularly violent criminals, instead of giving them shelter and succour. That too, we do not yet have. Both of these conditions require leadership of integrity and determination. Until these conditions are met, the frightening wave of serious and petty, violent and non-violent crime will continue.

MG: Do you think South Africa has fully dealt with the past and is now a mature nation?

EC:

We are on our way there. Having hosted the world cup has brought out a pouring of positive interpersonal sentiment that transcends racial, class and geographical barriers.

MG: You’ve fought for the rights of the poor, shared many experiences with them, and overcome numerous personal obstacles to reach one of the highest positions in the country. What advice would you give to young South Africans who are looking for a chance in life?

EC:

I would recommend hard work and focus. But my own life has taught me that this in itself is not enough. I was a hard working, ambitious and extremely focused kid. What made it possible for me to escape family adversity were social opportunities, which as a white kid I was able to obtain. So I strongly believe in the role of government in creating a more just and equal society for South Africa’s younger generation.

MG: In the past you’ve said, ‘I speak, I must speak. My life forces me to speak.’ How much more do you have to say?

EC:

There is a huge disparity and continuing injustice both in South Africa and the African continent in areas like education, healthcare and the basic amenities of life. I hope I have much more to say on all those three issues. I love being a judge. The challenges are exhilarating. However I’m not only a judge. I am a man living with AIDS and I did not feel I should remain silent. I have the energy and the voice to speak out and Africa and South Africa offers me the opportunity to do that.

Edwin Cameron – Witness to AIDS

‘Witness To AIDS’ is published in the UK by IB Taurus.