Implemented Environments: Solastalgia, Enlightenment, Red Tape and the Void

September 2, 2012

Mort Todd: Diabolikal Super-Kriminal

September 2, 2012One condition for the production of great art is that it must not be an instrument at the service of any master, but must be master of itself, its own aesthetic and message. It needs to be self-sufficient and autonomous, and speak and express the truths of its time. In our time, the planet is in danger because of human excess, so what has art to say about that? Can it help?.

A

Art expands itself by recycling – of a sort. Art and artists have always re-visited, re-interpreted, and re-shaped forms, motifs, themes, and tropes. This is not because we must conserve artistic concepts or reuse them because we have overproduced or run out of them, but rather because certain truths cross time and space. Artists go back to them again and again as to a deep well in our collective consciousness. They allude to works by other artists as part of ongoing conversations about human concerns and ideas of beauty.

Vik Muniz, Tiao as Marat by David

Vik Muniz, Tiao as Marat by David

Figures such as Michelangelo – who are iconic to us now – engaged in this form of “recycling.” It took place in Rome in the Renaissance, for example, when the most important ancient sculptures were discovered and unearthed in the villas of the Papal families in Rome. From a millenary dream, pieces like the Borghese Hermaphrodite or the Laocoon emerged. When visiting the excavation site, Michelangelo shouted: “Il Laoconte!” In a lost Sophocles play, whose existence we only know of from other authors referring to it, the priest Laocoon is killed by Poseidon-sent snakes, after trying to expose the ruse of the Trojan horse with a spear. Michelangelo, who was working on his Last Judgment at the Sistine Chapel, was invited to see the newly discovered sculpture and committed himself to restoring it and bringing it back to life. Of course, by identifying it as the murdered priest he linked everything to a very personal impression which forced him to complete the body of the figure which was unrecognisable. Hence, Michelangelo’s addition of a leg, two feet and an arm. How did he come to that conclusion? In my opinion he would not have been able to explain his reasons and anyway he was probably wrong. If the right arm the Florentine added had originally been not raised to hold a spear, it would be impossible to name the sculpture as that of Laocoon. However, when faced with the task he set himself, he applied his artistry to that of the ancients, with no regard for any archeological truth.

Titian,

Diana and Callisto, 1556,

National Gallery of Scotland

But what about the more literal contrast between the organic materials used to create works of art in the past and the ones we use today? The economy of art as debris is not a minor aspect of art. Where do these materials go? When art goes out of fashion, like clothes, it is disposable. Do these pieces end up in dumps or are donated to schools or other institutions for reuse? Does any public policy exist for works of art that are priceless – not priceless like, say, Titian but literally priceless, because nobody wants to bother even looking at them, much less buying them? In fact, only two out of ten artists represented by the top galleries in the previous decade continue to be important enough to be still represented at that level. The others slowly disappeared from the artistic scene.

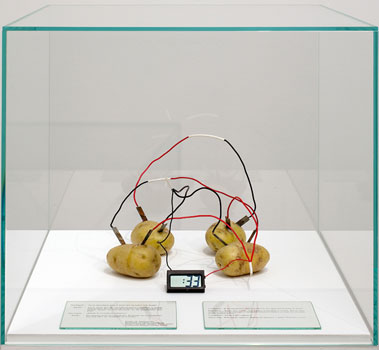

Victor Grippo,

Tiempo, 2nd version,

courtesy Inhotim collection minas gerais.

What about art that uses recyclable materials itself? During the seventies, the Italian movement called Arte Povera, or the Argentine informalism of Victor Grippo, created a type of art that is organic, perishable and recyclable. Grippo’s art consisted, among other things, of various configurations of potatoes hooked to a DC meter. He made art from various old tables, wheelbarrows, and other work implements. The problem with informalism and Arte Povera is that it was strictly linked to a theoretical discussion about the boundaries of the medium of art and its point was not in fact to save the earth or to place artists on a moral highground.From the antipodes of European “Poor Art” and, in the American West, Robert Smithson’s experiments with Land Art, which used the landscape as a medium to question the confining nature of exhibition spaces, we actually find nothing to do with the earth or how to protect it. Closer to the idea of rubbish as sculpture in a form as it has been presented for hundreds of years, John Chamberlain’s works are made of discarded refrigerators and cars that are crunched up by machines to create abstract shapes. His project is a commentary on American art specifically, and on the place of the beautiful in art. However, in all honesty, this approach still does not deal with the issue of recycling rubbish in order to reduce emissions.

John Chamberlain

Nutcracker, 1958

So what kind of art uses recyclable materials that, if not used in this way would have made any massive urban landfill bigger? Art and recycling sometimes comes together in eco-friendly art and similar types. Here the work is created with objects that have been basically rescued from the rubbish. It uses empty Coca Cola cans, for example which represents its concept, which is identical to what one can see – there is nothing hidden behind the facade. The problem with art like this is that visually it doesn’t work. Loud and defensive it is usually created by individuals who embrace a cause as a means of self-justification. A supersonic fast track for whatever guilt trip they might be going through in life, it provides them with a reason for existing which makes their “art” completely dependent on their own self-worth. That cannot be called art. It is too redundant and very quickly starts to be annoying. Maybe why it is so loud is because it can only be sold at craft fairs or at weekends. Art whispers, it never shouts.

Robert Smithson,

Spiral Jetty 1970, Great Salt Lake, Utah

Courtesy Mocala

Last year, a film on a Brazilian artist called Vik Muniz (who I did not particulary like before) took all this to a new level. The film worked on two levels: it made people aware of the situation with our massive landfills and at the same time created a process where everybody involved – from the viewers to the film’s protagonists – reviewed their own lives in real time. And that is Art. The film, directed by Lucy Walker, traces the development of a 2008 series of monumental photographic portraits Muniz took of trash. Called “Pictures of Garbage,” they were created by him in collaboration with the garbage pickers of Jardim Gramacho, a 321-acre open-air garbage dump just outside Rio that is one of the largest landfills in Latin America. Muniz worked with an unofficial workforce — or catadores, as they are known — that live off the dumps. In the process, they have become world experts in selecting rubbish for recycling. As a direct consequenc of this film, Brazil passed a law a year ago to eradicate open dumps and integrate the catadores into the recycling industry. The catadores are still an underclass but, in a way, that is the point of the film. Because the only thing that matters in life is one’s actions. It is about how we use our resources and abilities to make the lives of the people who will come after us if not better, then at least the same as the level we inherited from the generation before us.

Vik Muniz,

The Gipsy (Magna), from the series

Pictures of Garbage, 2008

“Wasteland” depicts Muniz’s efforts to help those at Jardim Gramacho take charge of their lives, while giving them a new perspective on the world through art. In the meantime, the viewer can see Muniz deconstructing himself. Without realising it, the same thing is happening to the viewer. It is a film on rubbish that uses the potentially distorting effects of cinematography – exaggeration, sentimentalism and monumentalisation of the hero – but at the same time gives the viewer the tools to discern both the formal aspects of the movie and the actual issue that is affecting the world in such an immense way and that includes the art world. It is the place of truth, love and respect in our lives. We are made to realise that our lives are in the dumps in a very literal way and it is up to us to pick ourselves up. A silent revolution might be beginning when patron, artist and victimised sitter feel true empathy and decide to do something about it. It is our life after all. At that very moment, we make a connection through space and time and then transformation is possible, if we desire it. That is the real power of art – to connect us, to help us confront the dangers and challenges of our age.