Italia- QUO VADIS

August 14, 2011South Africa’s Life of Wine

August 14, 2011Financial tribulation could well get worse, a lot worse: the world economy has fundamental problems that are not being resolved or even acknowledged, argues Jon Goodwin.

Since the Napoleonic Wars there have been four significant periods in which many sovereign states defaulted on their debts

Before 1945 countries defaulted on their debts mostly because of wars, internal political strife and the disruption of trade resulting from conflict. Since World War II however, most debt crises have been triggered by economic shocks (the big exception is Russia and Ukraine after the dissolution of the Soviet Union). In all instances of default, governments failed to insulate their economies and protect their citizens from conflicts and economic downturns which history should have taught them were inevitable.

It boils down to the desire for power and greed. It’s not just elected officials and dictators who are susceptible to this. The general populace also prefers to have its cake and eat. They tend to prefer incurring debt rather than increasing taxes or cutting spending. Ironically this pay-later mentality makes their economies more vulnerable to downturn and ends up compromising citizens’ standards of living. This has been true throughout history. It’s led to the crumbling of empires and redistribution of both power and wealth.

The current crisis did not start with the downfall of Bear Stearns or Lehman Brothers, nor did it begin with Bill Clinton’s mandate to the Department of Housing and Urban Development to increase home ownership rates among America’s poor. Nor is it primarily due to Clinton’s repeal in 1999 of the Glass-Steagall Act of 1932 that regulated financial institutions. It wasn’t even the subsequent failure of the US Congress to regulate the housing industry. Not the second Iraq war, funded principally by the US and the UK, (neither of them has sought to recover the war’s cost by taking royalty interests in Iraq’s petroleum reserves). These decisions just exacerbated a deeper problem at the heart of developed countries, a problem enshrined in law decades ago. It’s profoundly uncomfortable to look at this problem – the use of social security programs as tools for the maintenance of political power.

During the Great Depression the United States, following Germany’s nineteenth-century lead set up social programs, ‘safety nets’ for its citizens. Democrats, ironically the party that espoused the right of Americans to own slaves, with Franklin D. Roosevelt, FDR, in the White House enacted the so-called New Deal, a series of commercial regulatory and entitlement programs supposed to lift the country out of its economic pain. Social Security is funded by a tax on wage earners to provide income and medical benefits to pensioners and the disabled. Japan and Western European nations adopted similar programs.

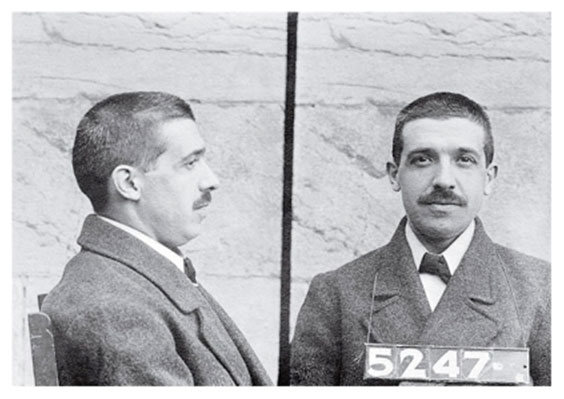

The mathematical framework for all this is the same as that used by a firm known as Old Colony Foreign Exchange Company of Boston. It funded its capital requirements by issuing notes which promised to pay a whacking fifty percent interest after only 45 days. Investors loved it. Word quickly spread among Boston’s business community. Requests for the firm’s notes increased. Old Colony obliged. Everything was rosy. But one day Joseph Daniels, a furniture dealer in the city, who had supplied Old Colony and claimed that he hadn’t been paid enough, sued. Word of the suit spread quickly and a few of Old Colony’s investors showed up demanding the return of their principal. Old Colony paid them. Shortly thereafter the Boston Post published a favorable article regarding the firm and the returns it paid. On the same page was an advertisement by a bank offering a mere five percent annual rate on certificates of deposit. The next day Old Colony was inundated with requests to invest. Its capital base swelled.

All of this activity was brought to the attention of Clarence Barron. The publisher of Barron’s, the financial paper, undertook a fundamental analysis of public information regarding Old Colony. He saw something was amiss: in order for Old Colony to meet its financial obligations there would have to be 160 million postal reply coupons in circulation; but, according to the United States Post Office, they had only issued 22,000. This revelation incited a run on Old Colony. The firm paid out $2 million before running out of funds.

Old Colony’s chief financial engineer and founder, practical mathematician Carlo Pietro Giovanni Guglielmo Tebaldo Ponzi a.k.a. Charles was not around by the time FDR signed the Social Security Act into law 1935. Ponzi had been deported to Italy after serving out sentences for mail fraud and larceny. He had bilked investors of $4.5 million.

Ponzi’s scheme shares the same central feature as FDR’s New Deal: the unfunded liability. The difference is that whereas Ponzi’s unfunded liability was easily quantified, FDR’s is not. That’s because it’s impossible to divine the future demographic composition of the population and the economic prosperity of the nation. And you need to be able to do this in order to estimate the future benefit obligations. Politicians keen on staying in power are better placed than unscrupulous businessmen in one respect: they can influence their actuaries’ assumptions. Worse, these unfunded liabilities relate to the future and that means they don’t feature in governments’ accounts. Instead, these liabilities are treated as ‘off-balance sheet’ obligations. You might only get to find out about them in addenda to governments’ financial statements or not at all. Just think of Enron.

Unfunded liabilities are rarely reported in good detail. That makes it extremely difficult for economists, traders, investors, voters and serfs to assess how much of a burden lies on a country’s shoulders. But here’s what we think we know: 75 years after FDR’s Social Security, the estimated present value of the US’s unfunded liability for entitlements stands at $79.44 trillion. That’s a staggering $256,804 per citizen or $721,023 per taxpayer. In 2010, entitlements represent the largest component of the country’s federal budget at $1.5 trillion . The unfunded liabilities of Japan’s social program is in peril in the same way. As for Europe, a study for the US National Center for Policy Analysis, published last year (using data from 2004) concluded that the “average EU country would need to have more than four times (434 percent) its current annual GDP in the bank today, earning interest at the government’s borrowing rate.” My firm, BarraMetrics estimates Japan and the US would both have to set aside more than five times their current annual GDPs to meet their future entitlement obligations.

As well as paying entitlements, governments will of course need to fund current and future budget deficits as well as potentially redeem future debt if they are unable to refund it. The US intends to borrow in excess of two trillion dollars for these purposes in 2010 bringing the country’s national debt to $14.8 trillion by the end of the year. That’s more than its GDP. EU countries will borrow in excess of $1.72 trillion on aggregate and Japan $479 billion.

All Ponzi schemes depend on things going well without interruptions in order to cover the schemer’s fraud. In Old Colony’s case it was that the post-office would continue to issue stamps. More recently, Bernie Madoff wagered that the stock market would cope fine with any significant economic downturn. Those who trusted him lost more than 11,000 times what Ponzi had cost his investors. The politicians who set up Social Security schemes in the developed world were betting that the populations of their countries would grow uniformly, indefinitely. Preposterous, of course. But at the time with the world coming out of the Great Depression people wanted to believe it. Returning to our old analogy, they wanted the free fish. The United States, Europe and Japan are all on a collision course with the same destiny that befell Ponzi and Madoff. Simply put, the scheme depends on worker numbers, which have been declining, and are set to continue going down in the foreseeable future.

There’s no hope these programs, as things stand, can ever become solvent. Governments will have to adopt substantive austerity measures in order to address their fiscal deficits. History of course has illustrated that politicians, particularly the popularly elected variety, do not have the backbone to take such action until external forces compel them – witness Greece.

Investors can bet on the reckless decisions of power hungry politicians and their greedy electorates. Known as idiot arbitrage, they’ve focused their attention on easy prey, the low hanging fruit, Greece, Portugal and the Euro. While their assaults in Europe are not likely to abate anytime soon, it is highly likely Japan will be the next target, followed closely by the US.

At its peak, this coming earthquake will be so much stronger than the tremors felt in Greece. There simply is not enough available liquidity to plug the $5 trillion dollar annual fiscal deficits of affected governments and refinance many trillions of their debt coming due over the next several years. The total resources of the IMF at the end of February stood at $591.7 billion with a one-year forward commitment capacity of $238.6 billion. That won’t go far! Neither the Chinese nor the Saudis operate their national treasuries as benevolent funds for spendthrift nations. Governments will have to turn on their printing presses. The consequence will be high inflation, high interest rates, low economic growth, high unemployment and the banishment of several hundred million of their citizens into poverty. Bernie Madoff’s $50 billion Ponzi scheme pales in comparison to FDR’s. As he stews in prison, politicians will soon eclipse his record. And they’re still running the show.

[one_third_last]

[nggallery id=19][/one_third_last]