Edward Akrout

December 8, 2012

Pam Ann: A Divine Comedian for a Divine Comedy (Around the World with Style)

December 9, 2012Since the World’s Fair in 1962, the Seattle Center – home of the Space Needle and the Museum of Rock n’ Roll – has been an important part of community life in Seattle. But time has its way with everything, and the bustling centre that had symbolised the future in 1962 had got a bit frumpy. When the community decided it was time to revitalise Seattle Center, a big chunk of that space went to artist and native son Dale Chihuly for a museum centred on his work. His vibrant, intense work in glass sculpture was just the tonic Seattle Center needed – and it gave the rest of the world a definitive look at the career of this signature artist.

Sun Space Needle

C

Chihuly is probably one of the most unobtrusively ubiquitous artists working today. The 71-year-old Tacoma, Washington native was at the forefront of glass sculpture – well, cross that out. Rewind. He has been at the forefront of glassblowing and glass sculpture as a fine art almost since he discovered the art while studying interior design as an undergraduate at the University of Washington, in Seattle.

Chihuly has had a wildly successful and incredibly prolific career. His work is found in about two hundred museums worldwide. He has dozens of public installations in more than thirty states in the U.S. and a couple dozen or so more in various places around the world – everywhere from the Victoria and Albert Museum in London, to the Bellagio Hotel in Las Vegas; from the Mayo Clinic to Disney Cruise liners. It seems you can hardly swing a cat without knocking some colourful Chihuly creation off the shelf somewhere and hearing it musically shatter. So what need of a new museum dedicated entirely to Chihuly – especially one in his home state, where Chihuly abounds? Washington state is home to twenty-three public Chihuly installations and his work is found in no less than ten museum collections there.

Sun On Mound

It’s a grumbling question that was asked by some Washingtonians when the Chihuly Garden and Glass was announced a couple of years ago. It was to be a 1.5 acre museum and sculpture garden dedicated situated at the foot of the Space Needle in the Seattle Center – the grounds of the 1962 Seattle World’s Fair. Chihuly’s output was so prolific – almost a factory level of production really – that he’d begun to be criticised as more a businessman than an artist.

Sea Form Tower

It’s that prodigious output that tends to overshadow a basic fact about Chihuly as an artist. He really is AT THE FOREFRONT. He is, for all his ubiquity, probably the most inventive glass sculptor in the history of the medium. One value of a Chihuly museum – with exhibitions designed and works chosen by the artist – is to have a more or less definitive record of his artistic output. And previous exhibits around the world have moulded themselves to (or squeezed themselves into) existing spaces – hotel lobbies, botanical gardens, a medieval citadel. This space would be Chihuly’s to fill – to shape to his vision.

Gold Swirl Ball

And of course, another answer to that question is simply: Oh, reason not the need! The experience of a museum full of the sinuous forms and bursting colours of Dale Chihuly’s art is not something that can be totted up on a balance sheet. This seems to have been what Seattlites concluded when the Chihuly Garden and Glass opened earlier this year to pretty much universal acclaim. The Seattle Times critic wrote that, “On seeing it for the first time, it’s hard to remember what was there before.” (In fact, it was a 1962 vintage arcade and amusement park called The Fun Fair.)

Persian Ceiling Long view

While Chihuly’s output has certainly been prodigious, there are some major through-lines that arc over the course of his career. He has created twelve major series starting in the 1970s through the 2000s, as well as a number of large architectural installations. These are all represented in the exhibition, creating a comprehensive view of Chihuly’s career. And, of course, he’s created works specifically for the Seattle institution, most notably in the Glasshouse.

Sun Chandelier

There are eight galleries and three drawing walls in the exhibition hall, walking you through Chihuly’s career more or less chronologically. The most interesting of the early exhibits is the Northwest room. On display there are some of Chihuly’s early experiments with glass. This room features a Tabac Baskets table, wooden shelves with Baskets, Cylinders and Soft Cylinders along with Edward S. Curtis photogravures of Native Americans. While he’s certainly made no secret of this influence, it’s not something that is given much play in the media depiction of Chihuly’s work. Yet, it is clearly a formative influence. The baskets table is juxtaposed with the actual baskets on wooden shelves along an opposite wall. The glass baskets mimic the soft, slumped, rather legato forms of the old, used baskets. Gravity has done its work on the woven baskets, and this is mirrored in the glass forms.

Persian Glass House

A spectacular installation represents another major series the artist produced, this one called Seaforms, from 1980. This series developed directly from the baskets series when the artist was experimenting with ribbed moulds. The resulting pieces looked like seashells and so Chihuly segued into a period of making sea forms of various kinds. The sea form installation in Seattle is anchored by a huge tower of Chihuly’s signature, undulating tubes of glass, both clear and in various shades of blue. It is studded with small depictions of sea life – fish, starfish, octopi, shrimps – all delicately sculpted from glass.

Persians Above |

Space Under Persians |

From there one moves into perhaps the most mesmerising exhibit – the Persian ceiling. It is a bare room with a bench at one end, with a ceiling made up of glass Persians arranged facing downward on a pane of clear glass. The Persians are flower-like forms, with scalloped edges and swirling colours. They’re called Persians because Chihuly thought it was “an exotic name.” (They don’t have anything to do with Persia.) Chihuly has constructed a number of Persian ceilings at different installations. It is easy to get lost in the forms and the colours hovering over your head as they play with the light trickling in from outside.

Mille Fiori |

Mille Fiori Long view |

Forms and colours rule in the next galleries – the Mille Fiori (A Thousand Flowers) gallery, and the Ikebana and Float Boats. Chihuly has constructed Mille Fiori exhibits in many installations. Basically, the Mille Fiore exhibits consist of gardens of glass that fill an entire room. The viewer needs to walk all the way around the room to fully take in the forms. The references are botanical, floral, and at times carry echoes of undersea life, as in the Sea Forms.

The Ikebana and Float Boats are actual wooden boats sitting on a plexiglass “pond” that reflects the boats and their cargoes as if on actual water. One boat contains works from Chihuly’s Ikebana series, based on Japanese flower arrangements. The other is full of round glass floats in riotous colours and patterns. Chihuly first filled boats with glass as part of his “Chihuly Over Venice” exhibition in Italy in 1995, where they floated free on Venice canals. He has continued to work with this idea since.

Fire Chandelier

The Chandelier gallery contains several large-scale installations – several chandeliers and a tower. These have been exhibited elsewhere, including at his acclaimed exhibitions “Chihuly over Venice” in 1996, and “Chihuly in the Light of Jerusalem 2000” at the Tower of David museum in Jerusalem, which had over a million visitors. Chandeliers and towers are complex, three-dimensional forms, where numerous coloured elements are attached to an armature to create a unified composition. These works were originally exhibited mainly outdoors in organic spaces and – from the pictures and films shown of them in the museum’s theatre – were stunning in those venues. Indoors, however, they don’t impress quite so much. The room is too small, making them seem overwhelming. And they compete with each other to the extent that it’s something of a relief to move on to the next gallery – the Macchia Forest.

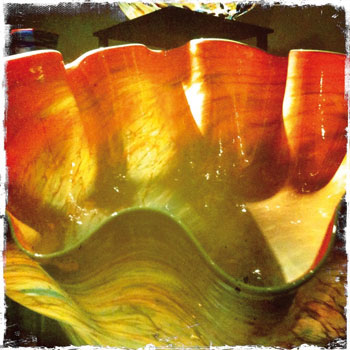

Macchia

Macchia are named after their spotted appearance – Chihuly dubbed them macchia after asking his friend and colleague Italo Scanga the word for “spot” in Italian. They grew out of the Sea Form series, and are large slumped vessels with wide mouths and undulating lips. In this they are also somewhat reminiscent of the earlier basket forms.

Macchia

In creating the Macchia, Chihuly wanted to explore his obsession with colour. The Macchia were an attempt to use every colour available to him in the studio. The vessels are one colour inside, with a white “cloud” layer in between that and an outer layer of patterned colour. The lip of each vessel is a contrasting colour. Arranged in a “forest” on top of pedestals and lit from above, the Macchia glow intensely and the colours are thrown onto the area surrounding each pedestal. The effect is immediately both soothing and invigorating. I think I’ve never seen such an intense shade of red as I saw in the “Carmine Red Macchia With Lime Green Lip Wrap.” This room creates an almost physical sensation of “drinking in” colour.

Macchia Clouds

In addition to the galleries, there are three “Drawing Walls.” Chihuly lost the sight in one eye in a car accident, and later dislocated a shoulder. He lost depth perception with the loss of his eye, and his shoulder injury makes it impossible for him to directly blow the glass. He now draws the forms he wants and directs construction, while others do the glass blowing under his supervision. He draws in a sort Pollackian action painting style, using tubes and bottles of liquid pigment to approximate how colours can merge and meld during the blowing process. The drawing wall gallery sports a large number of these concept drawings, which are striking art works in and of themselves.

Persian Ceiling Close

The big attraction, though – the best for last, the piècé de resistance – at the Chihuly Garden and Glass is the Glasshouse with its centrepiece installation:: a 100-foot long architectural sculpture of red, yellow, and amber Persians. Set as it is in a glass house inspired by Sainte-Chappelle in Paris and The Crystal Palace in London, it is constantly changing according to the light that comes through the walls, and as day fades into night and artificial lighting comes on. It hovers over an open space (available for private events by the way) that one can imagine filled with all sorts of upscale do’s.

Sea Form Tower

The gardens that the viewer moves into from the Glasshouse are a bit of an anti-climax after the Glasshouse sculpture. They do, however, reference a lot of the themes and motifs that have threaded through Chihuly’s career, including botanical glass forms mixed with actual plant life, with the two both contrasting and echoing each other.

Sea Form Tower Detail

There are four monumental sculptures in the gardens, but the one that stands out – indeed dominates – is “The Sun,” an explosion of yellow and orange medusa-like structures that hovers over a mound of black mondo grass. It’s worth a look.

And of course, towering over all of it, almost seconded to the museum as an exhibition itself, is the Space Needle. It is literally a few steps away from the edge of the garden and is reflected in the numerous coloured glass balls strewn about the gardens. It even peeks into the Persian ceiling. There’s an image that will no doubt become a Seattle cliché.

[note]

Photos by Catherine Turley and Tom Turley

[/note]

Speckled Gold Pink Flower

Nested Baskets

Blue Orange Baskets