Leviathan 7

December 8, 2012

The Divine Comedy

December 8, 2012Industrial design is as international and cosmopolitan a world as fashion. Designers all over the planet contribute to a diverse and vitally creative industry. But, through a confluence of factors, Italian design has always been the trendsetter in this world. Moving into an uncertain, post-industrial age where unsustainable resources and practices must be jettisoned at all levels, Italy remains at the forefront.

I

I once heard a fashionista say that “if it’s March, it’s autumn and if it’s October, it’s spring.” Well, in the industrial design world (that’s furniture, lighting and just about all products in between), we have something similar – if it’s January, it’s Stockholm, if it’s April it’s Milan, September it’s London, October Cologne – you get the idea. The never-ending round of annual shows means you could almost spend your entire working year going from one fair to the next.

At their allotted time, design communities in the major cities around the world play host to what they hope will be the most talked about, most attended and most exciting show of the year. London recently wrapped up its annual Design Festival, its tenth year of festivities. Following hard on the heels of other major events across the capital in 2012, London Design Festival aimed to get the whole city involved with over two hundred events planned across ten days. It was a glorious success, if Julie Lansky’s at-times enraptured review in the New York Times is any indication. “Apologies to Milan and Tokyo,” Lansky wrote. “Regrets to Stockholm and Paris. Forgive me Eindhoven, Berlin, Barcelona, and most especially New York. But London is the design capital of the world.”

Yet, as Lansky put it, “despite the scale [of London] and the presence of almost 300,000 visitors in 2012,” the Triennale of Milan still carries the most cachet in the design world. Lansky quoted one British journalist, who, during the London show, sniffed that “everyone with half a brain still launches in Milan.”

So what is it that gets the rest of the world so excited about Italian design? Since 1923, when the first Triennale was held, Italian design has always had the idea of bringing together the triumvirate of industry, production and applied arts. The show itself has attracted its fair share of international heavyweights, including architect, founding editor of Domus magazine and, arguably, the godfather of Italian design, Gio Ponti.

Gio Ponti Superleggera chair designed 1949-52

He was one of several architects to foster the notion of a national identity through design. After 1945, with little or no work from the state and with no formal industrial design schools to speak of, many Italian architects turned to furniture and product design for wealthy clients. It was through this process that they gained an understanding of materials – something that was to become invaluable in the economic miracle years of 1958-1963, when Italy sought to re-brand itself as an economic, industrial and cultural power. These were the values that Italians took with them in the wave of emigration during the 1950s, especially to the US, who had given post-war financial support. The international outcome can be seen in the likes of US films such as Three Coins in a Fountain and Roman Holiday, or in the coffee bars that sprang up in London, as well as the fashions, including slim-fit trousers and short length jackets, known as bum-freezers! The world was tired of post-war austerity and wanted to live la dolce vita.

Italy was by now, a nation striving to whole-heartedly embrace the production of modern materials such as plastic, moving away from more traditional roots, like the British with their Arts & Crafts. Companies such as Kartell, established in 1949 by chemical engineer Giulio Castelli, the Olivetti family who had been long-time supporters of the importance of design, and Zanotta, founded in 1954 by Aurelio Zanotta, all worked towards the common goal of changing the status of product design from functional to desirable. Creating links with artistic practitioners who often worked at the edges of the accepted norm, pushed the boundaries both in terms of form and how the material responded. The new shapes and colourful surfaces provided a metaphorical aspect in addition to a functional necessity within a domestic setting. Industry and commerce were now linked with art and culture.

In 1957, Italy had entered the European Economic Community, requiring exhibitors at that year’s Triennale to concentrate on providing the right goods for an expanding European market. As rising young, affluent professionals sought to distance themselves from the previous generation, Italian design became a by-word for the modern style.

It was this word style which would help keep Italian design alive during the 1960s when the economic recession hit Italy while other countries such as Germany and Japan moved ahead in the technology stakes. Forced to compete, Italy traded on the links it had created between the arts and industry. By 1966, the levels of industrial production were three times what they had been just fifteen years previously.

Italian design also had another advantage – size. In 1971, 82% of Italian manufacturing firms employed fewer than five workers, which meant they were still able to compete, whilst the relatively low wages and overhead costs weren’t adversely affected by the economic crisis.

By the late 1960s and early 1970s, design – or more importantly style – was still an essential export, but by then Italian design was struggling. Many critics thought capitalism in design had sold out and that there was no longer any critical debate in the production of what was being churned out. Style was no longer as important as it had been just a few years earlier, and with the looming oil crisis, materials were often scarce.

Archizoom Safari seating designed 1968

Anti-Design was taking hold with groups such as Archizoom and Superstudio creating references to popular culture instead of high art. Design needed new relevance, and these groups, born out of the political clashes, with a radical and experimental approach to designing, presented a series of projects aimed at highlighting just how negative the existing modernist orthodoxies were. Italian design was once more at the forefront of raising awareness and awakening the consciousness of the designers, who themselves became philosophers, imbuing their products with political meaning.

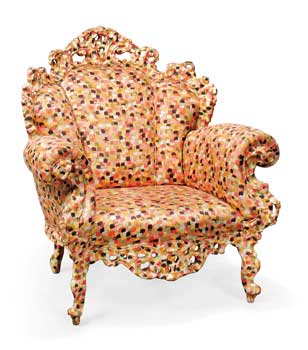

Alessandro Mendini Proust armchair originally designed 1978

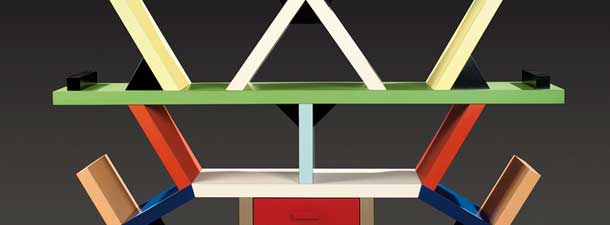

In their thesis entitled “Banal Design”, Studio Alchymia – founded in 1979 by Alessandro Mendini – asserted the idea that the meaning of the design lay no deeper than in its surface decoration. It was an ironic attempt to subvert all notions of what constituted good taste and break the ties that linked Italian design to Modernism. The crazy colours and brightly patterned surfaces reached an apogee in the work of Memphis, a studio founded in 1981 by Ettore Sottsass. In the studio’s first exhibition at the Milan Furniture Fair, the response was overwhelming. Visitors could easily see and understand the idea of mass culture, and how the design world had come to reach this melding of history and popular culture. Italian design was able to quickly illustrate all of this with witty references and, by being striking in appearance and irreverent in its attitude, suggested that the good times had returned.

Memphis ‘Carlton’ room divider, designed 1981

Throughout the 1980s, Milan secured its position as “the design capital of the world.” The two principal strengths that Italy had developed during the post-war years came to dominate the idea of what design should be and was capable of – flexible, progressive industry on one side, and creative and versatile individual designers on the other. By fixing these ideals early on, Italian design was ready and able to move towards the service industries that came to dominate in countries such as the US, where once manufacturing had been the mainstay of economic development.

Joe Colombo 4801 chair designed 1963-4

It was only as the global recession of the early 1990s hit, did anyone question the need to dampen the exuberance and posturing of post-modernism, briefly beloved by designers.

Ironically, it is exactly the multiple references, consumer options and cultural pluralism that Italian design had plundered, which would see it evolve throughout the 1990s and into the new millennium. As the world became smaller and the rise of technology brought nations closer together, Italian manufacturers looked outside of their own country for what was new and changing. A small group of little-known, international artists, designers and makers from France, Britain, the US and Japan were among those commissioned by the largest suppliers to design and develop products for the Milan Furniture Fair. Just as in the fashion world, industrial design wanted to launch a new collection every April that the world’s design community would be hungry and waiting for. These designs were often born out of conversations and prototypes the designers had begun experimenting with. But for manufacturers they represented capsules of their overall collections and helped them to position themselves as luxury furniture companies.

Marcel Wanders, Knotted chair, designed 1996

It is a formula that works while the good times roll, but as another global recession hits, along with the realisation that the world’s resources are finite, Italian design once more needs to become relevant to the times we live in. Some critics have said that it has reached middle age, with a formulaic approach that has become tiresome – or even that it has realised the end of its natural lifespan. The plain truth is that we simply have too much – too much product, too much choice, too much desire to own something. This is a situation that Italian design has readily contributed to and which is simply not sustainable any longer. The responsibility now lies in the hands of not just designers and manufacturers but with all of us.

Artek stand Milan 2009

In 2009, the Finnish manufacturer Artek, launched their One Chair is Enough campaign to show that by buying smarter – in this case a timber module that could form both a chair or a table base – consumers could be directed towards more thoughtful and informed purchases.

It is these ideals that the Milan Salone Internazionale del Mobile (to use the official title of the fair) should embody. The 2012 show saw an increase in the number of small, Italian, family-owned companies participating, which operate on a level more akin to industrial artisans, although they work with new production methods and techniques. The results have proven to be a continuation of the “Made in Italy.” How things develop going forward, of course, remains to be seen. It is surely at times such as these, however, that creativity works hardest. If ever there was a moment for Italian design to promote the role of responsible design, it is now.