Nonno Panda and the Beautiful Little Girl

December 8, 2012

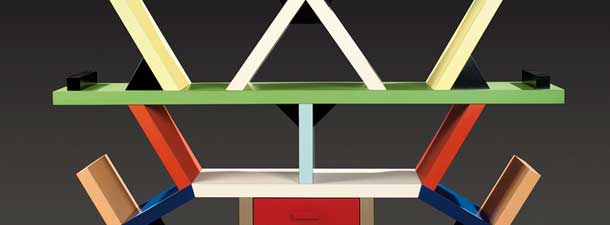

Italian Design Still Leads the Way

December 8, 2012The Blind Spot in Africa: The Forgotten Horror of Sudan

T

When you go on your mission, if you find them, kill them; sweep them away; eat them. Do not bring me any prisoners of war. We have no quarter for them.

– Kordofan Governor Ahmed Haroun (government radio broadcast to Sudan’s army last October)

The world is gripped by the continuously unfurling, multiple crises of the Middle East – Syria, the uncertain Arab Spring, the war clouds between Teheran, Israel and the West all vie to hold centre stage. The same can be said of Europe’s economic woes; the muscle-flexing of an emboldened China as a naval power, and the growing territorial and maritime disputes with her neighbours; and, not least, of the future of the White House. By contrast, as ever, sub-Saharan Africa goes mostly unnoticed by the media and the collective public opinion of the planet, if such a thing exists. Nevertheless, some stories – the success of the African Union force against Al-Shabab in Somalia; the pursuit of the Lord’s Resistance Army; a UN resolution for intervention in Mali; new allegations of skullduggery in the Congo; and South Africa’s violent standoff with its mining unions – have managed to get into the global headlines and stay there, more or less.

The new charges implicating the Rwandan and Ugandan militaries in backing, indeed controlling, the M-23 militia, which has perpetrated so many atrocities in the Congo, are indeed disturbing. The fact that such an endless conflict continues to generate such a multitude of unpunished crimes should be held up to the light. Just as it is not too late to see Radovan Karadzic stand in the dock at the Hague for the Srebenica massacre during the bygone Yugoslavian War, these offenders should also be relentlessly pursued. And yet Sudan’s President Omar al Bashir, the only sitting head of state in history to be indicted by the International Criminal Court for genocide, war crimes and crimes against humanity, travels the world freely, his right to freedom upheld by the African Union, the Arab League, the Non-aligned Movement, Russia, China and Iran. The last three, not incidentally, are his main arms suppliers, together with Moscow’s proxy, Belarus – a nasty dictatorship in its own right. And while the media and so-called international community correctly decry the monstrous conduct of Syrian president Bashar al Assad against his own people (minus of course Russia, China and Iran), there is enduring silence over the equally egregious conduct by Khartoum’s hard-line Islamic military regime against South Sudan, the people of South Kordofan and, still, Darfur.

There exists a common misconception that despite border tensions and the near eruption of a new war just months ago, Khartoum, albeit grudgingly, co-exists peacefully with South Sudan, after its hard-fought, thirty-year struggle for independence that claimed more than two million lives, most of them South Sudanese. The truth is anything but. Since most of Sudan’s vast and largely undeveloped petroleum wealth resides in the South (though it must pass through pipelines in the North to get to market) Bashir’s regime, covetous of this oil and disdainful of its mostly Christian and Animist neighbour, continues to wage de facto low-level war, not merely through the constant threat of its conventional military forces on the border, but by actively arming and training proxy militias. It is especially content to take advantage of South Sudan’s enduring tribal enmities. Ordinary South Sudanese pay the greatest price for this situation. Their tragedy is compounded further by the clear evidence of widespread corruption and abuse in the South Sudanese government, from rumblings of mutiny in the military, through graft, to extra-judicial killing by the army and police. Although Stetson-hatted President Salva Kiir is, by all accounts, a decent man, he is doing a tough job in almost impossible circumstances, in one of the poorest countries on earth, lacking every possible dimension of working infrastructure a nation needs to be functional, after generations of pitiless war. That the South turned off its oil wells in response to Khartoum’s aggression in recent months (they still aren’t working) has exacerbated the situation since it cut off South Sudan’s primary source of income. Most of its people survive on the equivalent of some 70 US dollars a month, or less.

But it doesn’t end there. It has to be characterised as astonishing that the UN and the AU both state with a straight face that the decade-plus-long conflict in Darfur has ended. Darfur’s population is predominantly Sufi, adherents of the mystical tradition in Islam, traditionally the most tolerant and liberal strain in the

Muslim world. They are regarded by Khartoum as apostate and heretic, a rationale that has helped Khartoum to ideologically justify the slaughter of the Darfuris. Millions live in the misery of displaced people’s camps, daily subjected to hunger and disease in the most primitive conditions. Their plight still includes the routine application of violence by the state in the form of aerial attacks from helicopter gunships and bombers (often disguised with UN markings), raids by the regular Sudanese army and paramilitary police and by the core weapon in Khartoum’s arsenal of war by proxy, the Janjaweed militias. So it comes as no surprise that the various rebel factions in Darfur have formed a unified front. Whereas before they struggled to achieve greater inclusion in Sudanese society and an end to human rights abuses, they now pledge to fight on, with virtually no means, until they are dead or the dictatorship in Khartoum falls. Fatality estimates range from 200,000 to 400,000 so far in Darfur, most of them civilians. And the death toll is still rising.

But where the bloodletting is now truly out of control is in the mountains of South Kordofan State, a highland region home to one of most ancient peoples on earth, collectively called the Nuba – the very same Nubians of antiquity and biblical legend so memorably photographed once by Leni Riefenstahl. The Nuba fought alongside the South Sudanese for generations. Upon South Sudan’s independence, Khartoum decided to wreak vengeance upon the Nuba for having chosen the wrong allies. It is nothing less than a genocidal campaign and the means the Nuba guerrillas have to resist Khartoum’s juggernaut are as slim as those in Darfur. The catalogue of barbarity meted out there by Bashir is also grimly familiar.

Indiscriminate aerial attacks on populations are the norm. And, as in

Darfur, rape, torture, summary execution of prisoners, the elimination of whole villages, starvation through a deliberate stranglehold on food supplies and humanitarian aid, and the literal enslaving of captives are orders of the day in Khartoum’s scorched earth policy, so chillingly encapsulated by the Kordofan governor’s exhortation to his troops last October, quoted above. It is a war with extermination as its goal and cannot be confused with anything else. But it doesn’t make it onto the headlines much, though it is Africa’s, and the planet’s, newest genocide in the making. It is impossible to calculate how many have died so far, but it runs into the many thousands. The butchery shows no signs of abating.

When the guns and the machinery of war that perpetrate this killing are mostly made in China, Russia, Belarus and Iran, it is also a curious omission from the dialogue in the United Nations. Do these same weapons count more in Syria than they do in Kordofan? Does the culpability of Assad’s armourers somehow mean less when their victims are African? Where is the outcry? Where is the discernible international effort to halt this barbarism? Where are US President Barack Obama’s pre-election promises to the Sudanese people? It was former President George W. Bush who first labeled the crimes in Sudan as a genocide, so if Democrats won’t act in Sudan, where are the Republican voices in the US Congress? Why are the Nuba and the people of Darfur not on the moral agenda of the West as it decries events in Syria? As this issue of Dante goes to press, it is sadly one of the few venues in the global media where you can even read about this situation. For shame. In Sudan, the much-derided “Dark Continent” does indeed remain shrouded by a black veil of silence.