Food for Thought

April 1, 2013

Relief Riders International

April 4, 2013Gods and Modernists

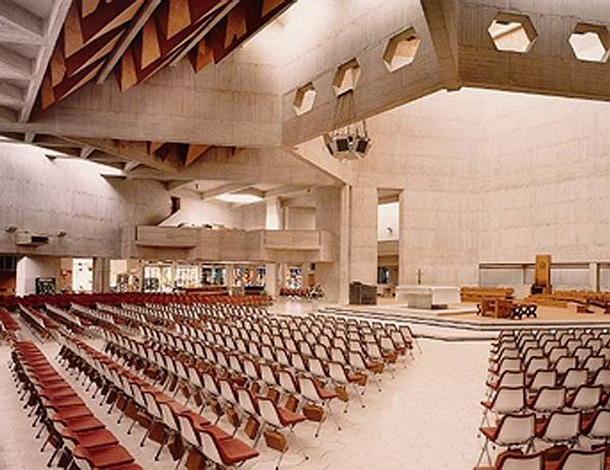

Liverpool Metropolitan Cathedral of Christ the King - 1967. Designed by Sir Frederick Gibberd

The edicts of the Second Vatican Council in 1961 had far-reaching effects throughout the Catholic Church. These effects reached even into the physical spaces where worshippers lived out their faith. The spirit of modern architecture came into dialogue with that of the ancient faith. That dialogue has been decidedly mixed in effect.

O

“Open the windows of the Church and let the breath of the Holy Spirit blow through it.” So said Pope John XXIII in his opening statement to the Second Vatican Council held in 1961. In the one hundred years leading up to that moment – since the first convocation of the Bishops – the world had changed beyond recognition and the Roman Catholic Church needed to keep up. Whether it was expected that the changes in the church would be as quite as far-reaching is still a matter for debate, but with such incendiary words spoken openly, there could be no turning back. Numbers of the faithful had been in steady decline for many years as the human race moved towards an ever more secular society. Modernism would prove to be the solution for the ailing dogma.

After millennia of steadfast liturgy – itself derived from an even earlier Greek word meaning a public duty carried out by those at the Temple – the entire arrangement of rites, services, blessings and sacraments would be swept aside in favour of a more publicly engaging process. Gone were the words spoken in Latin – irrespective of the local language – and read by a priest who faced towards the altar and away from the congregation. So far away, in fact, that the majority of congregants felt as if they were nothing more than onlookers, simply staring at a series of ancient rituals. This, of course, was originally of benefit for the Church. It preserved the air of mystery and authority surrounding the services performed by the select few on behalf of the masses.

By the mid-20th century, time and culture were deemed to be more important and a decision to perform Mass in local dialects was made, thereby immediately engaging the faithful few who still attended. With this monumental change, the Council gave their blessing to what became known as the “Constitution on the Sacred Liturgy”, which essentially provided a set of guidelines for the Church architect and artist to follow, in order to meet with this new approach to worship. In the most dramatic move for over a thousand years, the altar was placed in the centre of the congregation. All those hierarchies and barriers, reinforced by physical railings and hardened customs were smashed and broken down with one swift stroke. The reverence and esteem that priests had once commanded were now gone as they performed their rites on the same level as the laity, right in their very midst. The ceremony itself was now seen as a physically and emotionally involving act whereby the architecture and design of the church stimulated maximum participation by the worshippers.

Designing buildings with only one focus of worship, i.e. the central altar, formed a new relationship between the church and the user. The space that surrounded and enveloped those inside literally and figuratively wrapped everyone in the same worship space. Church floor plans had to be seen to provide unity whereby both the priests and parishioners appear to offer the sacrifice together. Through this act of involvement, the Church hoped to found an ideal of community and social cohesion, giving rise to an increase in congregants attending Mass.

St Paul’s Glenrothes stained glass

Modern architecture operated with a similar ideal in that a collective identity could be formed through the creation of new buildings. In a post-war society, the arguments for social and religious tolerance through re-building were a powerful force. Pressure from the European continent to follow the new guidelines exploded within the UK and gave rise to some of the most prominent and progressive religious architecture the country had ever witnessed.

With modest exteriors devoid of decoration, and simple interiors stripped free of any exuberant excesses, the worship experience became one of powerful contemplation, almost intellectual, with an air of austere calm. In a move designed to break free entirely from earlier architectural dogma and to reject its symbolism with its links to the past, architects developed a new geometry of forms and surfaces, on which light would play an important part. Using a limited palette, often little more than bare concrete, architects sought to communicate a truth and beauty in the ideals of the material. A single steel-truss on show, seen as structurally pure – and thereby equally spiritual – was afforded the same status as the statues of the saints or images of martyrs had been previously. These, however, had been removed or at the very least discouraged, as had the canopies and pulpits, all with a nod towards accommodating the lay reader. Certain decisions, though, such as the size, shape, material and character were being left in the hands of the local priest, who used judgment and discretion when considering the ability of the chosen architect and artists, many of whom were from the secular community.

Clifton Cathedral interior, Bristol, UK

Once the altar had been freed from the constraints of the narrow apse of the building, a new vitality was realised and the previous internal arrangements could break free of tradition and experience into an era of openness and light. Seating that had once been in military, regimented rows was suddenly allowed to take any form it wanted – radial, elliptical, spiral, triangular or even pentagonal. Side chapels were removed to prevent private worship during mass, forcing a collective consciousness towards the one altar, where concelebrations now took place.

The altar itself was stripped of decorative textiles, cloths, silver-plate and icons. Candlesticks and ornaments were placed to the side, often on the floor, as a way of promoting the sanctity and purity of the altar. Daylight was allowed to pour in from windows in the circular vaulted roof space above, bringing the metaphorical light from the Holy Spirit into the centre of the church. Even the floor, that had always been solid and flat, now sloped towards the central altar but was no longer simply bare stone. Rugs and carpets were commissioned alongside contemporary stained glass windows, bathing the interiors with a wonderful vocabulary of colours, forms, materials and textures that some said were reminiscent of the painted medieval churches they were trying to escape!

Clifton Cathedral interior, Bristol, UK © Catherine Roperto

The contemporary church became a living, forward-moving beast, which was no longer hamstrung by outdated dogma or ritual but rather became a progressive refuge for enlightened thinking. The physical forms and materials spoke to a younger generation, who were more attuned to the thoughts and expressions of Modernism. They were of course, the core of what would be the next congregation.

Not all of this new approach was born out of high-minded idealism however. In truth, post-war building costs had risen sharply, owing to shortages of building materials. Innovation in structural design became widespread with the advent of the concrete and steel-frame building. It was a method tried and tested in commercial building schemes and since the end of the Second World War, it had also been used to great effect in erecting low-rise, high-density social precincts including housing, schools and hospitals.

Vatican council

It was the advent of this approach that saw rise to prominence of perhaps the most important practice in post-war religious architecture – Gillespie, Kidd & Coia. Their work for the Roman Catholic Church included more than ten churches spread throughout Scotland. Perhaps their most important project though was for St Peter’s seminary in Cardross, Argyle & Bute. The building itself was testament to the speed of changes the Second Vatican Council had instigated, with the process from design to completion taking approximately seven years.

One of the key matters arising from the Council was the training of priests, which had previously been carried out in Rome. This regulation was now relaxed to allow local parish theological colleges to carry out the necessary tuition. They were, however, expected to integrate fully with the local community, providing a combination of spiritual and pastoral care. The experience of low-rise, high-density architecture was to prove invaluable here, as a greater number of functions took place within one site.

St Peter’s Seminary

Such colleges as St Peter’s best expressed the desire to unify church and community. The building adhered to the same method and materials used in church building: formed in concrete with white painted walls and curved, varnished wooden ceilings, it firmly emphasised meditation, contemplation and reflection on theological matters. Just like the stained glass used to let in the glory of the Holy Spirit’s light, extensive glazing throughout the college provided an air of openness and transparency whilst providing tonal warmth to the interior.

Despite the good intentions and maybe as a consequence of the shift in focus towards the laity, the seminary never fulfilled its potential or capacity. Although the building is still standing today, it is in ruins and remains on several “Endangered” and “At Risk” lists.

Within ten years of the Vatican Council, it is estimated that 100,000 left the priesthood worldwide and that many enclosed orders of nuns simply drained away. Outspoken theologians began to question papal infallibility and the wisdom of many of the decisions taken by the Second Vatican Council. Yet the facilitating of liberal ideas and belief in the congregation as well as the existence of God, was helped in no small part by modern architecture and design. With the parallel tenets of community and spirituality, social reconstruction through Modernism had seemed a very real possibility. The openness and airiness given over to religious spaces, had allowed the congregation at last to become part of their faith as well as practising it. The wider outreach into the community was realised but by then, the community was simply much too wide. As Gillespie, Kidd & Coia partner Isi Metzstein once said “Modern architecture is very eclectic: there is nothing that is not allowed in modern architecture – as long as the spirit is modern”.