Nonno Panda and… The Urban Foxes

April 16, 2013

Leviathan 9

April 18, 2013Hero Cult: Two Thousand Years of Subversion

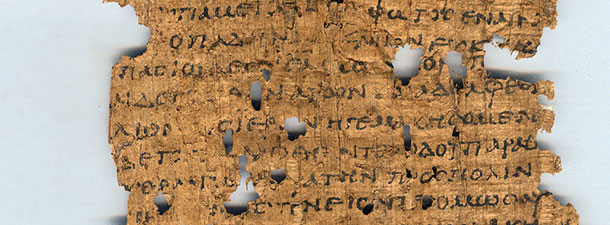

Papyrus from Oxryhynchus in Middle Egypt now in the Sackler Library, University of Oxford, containing elegiac verses by Archilochus.

There is nothing new under the sun. The shout of Punk may come with modern trappings, but it is a cry heard in many an era, in many forms. Ancient Greek poet Archilochus, who voiced that cry in his time, may justly be called the proto-Johnny Rotten.

S

Some poets live outside the margins of society. Shouting at (and to) the world, they bring necessary chaos to an otherwise ordered system. If we look back far enough and take the span of thousands of years, we start to see the recurrent nature of subversive poetry – and performance. Nothing has quite managed to reach the same proliferation as punk, for instance, but we can easily find an explanation in the accessibility and distribution of mainstream media, which only existed in the latter half of the 20th century. Other time periods have all generated their own misfits, their own Johnny Rottens.

Archilochus

In the Seventh Century BC., there lived a Greek poet, Archilochus. Scholars are reasonably certain (due to references to certain astrological events in the work of those who wrote about him) that he lived at around the middle of the century, some (indeterminate) time after Homer and a century or so before Sappho. His work has been classed on the same echelon as Homer, and he was frequently mentioned by later writers in antiquity – in fact, we have more testimonials from other authors than we have of Archilochus’ own poetry, very little of which remains.

Homer

-It is frustratingly difficult to reconstruct meaning and context in Greek poetic literature from that time. We are ignorant of so much, for so much of the ancient material has been lost. In many cases, we have only a few scraps of papyrus to give us tantalising glimpses into ancient works. The seventh century stood very close indeed to the birth of the written language. Copies were sparse, and poets were only just starting to feel their way around their art, which had carried through from the oral tradition in which we find the epics of Homer. Ancient poetry was composed for a variety of purposes; some were written for performance, either by choruses or a single performer, but with such a paucity of evidence it is difficult to tell with certainty what happened, where, and with whom, or if the content of the poems is fictional. For all we know, all of Archilochus’ poetry was written in a poetic persona, and in reality he might have been a market girl in Scyros. (He wasn’t. Probably.)

In addition to his fame as a poet – which was exceptional, according to ancient sources – he was known for being a divisive force. He was said to have been banned from schools in Sparta for expressing anti-heroic sentiments, saying: “Someone else is enjoying my shield now – a perfectly good bit of armour that I had to abandon next to a bush. But I saved myself. What do I care for that shield? To hell with it! I’ll get another one just as good.” (Gunnery Sergeant Hartman would be very unhappy indeed.) And yet, Archilochus defied this trickster persona by providing us with glimpses of a deeply passionate, idealistic man. He was a soldier himself, and held in high regard the qualities of a good commander. He frequently waxed philosophical about the realities of life, meditating upon friendship or fortune:

Everything is the work of the gods.

Oft when men lie flat on the dark earth

those immortals lift them up

and oft they throw on their backs

even those whose footing was firmest.

Then many sorrows are theirs

and a man wanders, yearning for his life back,

his mind distraught

The poetic tradition in ancient Greece was a hotbed of social and political discourse. The little that remains of Archilochus’ work suggests a turbulent, radical, fiercely intelligent character. He gained extraordinary fame as a poet, oft-quoted by historians and philosophers throughout hundreds of years (among them Aristotle and Ovid), but cut a controversial figure due to the vehemence and frequent obscenity of his poetry. The kind of vulgar language found in Archilochus’ poems is not unusual when compared, say, to Greek comedies, which were notoriously bawdy; it was probably the combination of this obscenity with venom that shocked readers and divided opinion. Pindar, a later lyric poet from the fifth century, wrote “I’ve often seen blameful Archilochus fattening himself on hateful words in his helplessness.” Was he commenting on the first seeds of the first-wave punks with those words? Did he see the same railing, the same unfettered outpouring? Punk made a meteoric impact on British society in the 1970s, making text of a hitherto unexpressed social and political subtext, allowing musicians to voice and the audience to live out their feelings of alienation and anger in a hopeless, impersonal capitalist society.

In ancient Greece, there existed a famous ritual: the Dionysian mysteries, which predated the written word and continued in various forms until late in the classical period. They were even adopted and developed by the Romans in the second century B.C. These were religious trance rituals often frequented by marginalised minorities, including women, the poor and the excluded, which involved the surrender of self to divine possession. What has this to do with punk? The raw energy we can see in recordings of live punk performances have more than a streak of surrender to them – perhaps not to divine possession, but of the self to emotion. John Lydon’s stage performances were notoriously extreme, and audience behaviour similarly grew to exhibit a powerful, unharnessed quality that rivalled the Dionysiac ecstasies of the Greeks. Patterns repeat across thousands of years; everything has changed, and yet nothing has changed.

The crack of punk thunder split the conservative sky – but offered no true, sustainable alternative, in part because the pointlessness of it was the point. Rather, it wrought changes in its own musical world, creating an alternative to the gentler strains of pop and rock. Interestingly, Archilochus is credited with changing the format of poetic composition from the traditional metrical forms of Homer to a new verse-form called elegy, a conversion that, though it seems a small change now in a world that spans goth to classical, was a leap of epic proportions at the time. While it is clear that Archilochus was not the true originator of elegy (we have elegiac inscriptions that predate his work), his gritty, unheroic realism reinvented poetry, and paved the way for theatrical performance of comic, lewd poetry, which eventually became comic drama. And he paved it well; in a fragment almost certainly referring to a prostitute, the poet presents us with the creative image: “She was sucking like a Thracian or a Phrygian sucking beer through a tube.” Archilochus was the first poet we know of to have used sexuality as the central theme to some of his poetry. Nothing was sacred; a family who reneged on a marriage promise received a venomous barrage of poetic invective:

Your skin no longer has the bloom that it once had;

now your furrow is dried up

the rust of ugly old age is eating you,

and sweet desire has made a break for it

off your once-beautiful face

assailed by many blasts of wintry winds.

The guilty family is said to have committed suicide after being flayed by Archilochus’ sharp pen, though how much of this was wishful thinking on the part of Archilochus and his supporters is open to debate.

The Sex Pistols – Sziget music festival – Budapest

Criticised and idolised, reviled and loved, Archilochus attained immortality: his hero cult was established in Paros, his home town, and the requisite plethora of origin and biographical myths proliferated for hundreds of years after his death. How much record will remain of our culture in two thousand years? With countless gigabytes of information stored on countless hard drives and thousands of websites paying homage to the heroes of pop culture, it is easy to get too comfortable in the assumption that multiple electronic copies mean permanence; that they will leave a sturdier legacy than the fragile papyrus fragments of the ancients. But who can tell what the true rate of decay will be? Perhaps one day, the sparkling, foul-mouthed Johnny Rotten and the Sex Pistols will also be remembered as enigmatic philosopher-ghosts of the past – but their presences and the repercussions changed society and literature forever, shaping it for years to come. In a sense, Johnny Rotten has his own heroic cult. Though their groundbreaking predecessors already existed several years earlier, the Sex Pistols have become the figureheads of the tectonic musical shifts of the 70s, and Johnny Rotten has effectively been deified by the cult of punk. With his own disavowal of that association with his music (John Lydon was vocally against calling The Pistols a punk band), I have to wonder: Would Archilochus be equally incensed by his own hero cult?