In Transition: The Resilience of the Women of Tajikistan

August 10, 2022

On the Slow Train to Somewhere

August 15, 2022While he remains almost unknown in his native England, 17th century pirate Bartholomew Sharp, like many of his contemporaries, left an indelible mark on those who plied the waters and lived along the coasts that he terrorised in the Caribbean and, most especially, along the Pacific Coasts of South and Central America.

W

When Oliver Cromwell’s troops seized Jamaica in 1655, the first English governors feared a Spanish reoccupation of the island. They invited the buccaneers of Tortuga to use the harbour at Port Royal as their new headquarters. Until then, the English pirates had operated in the shadow of the French, who were effectively stealing the western side of Hispaniola from Spain. Under Henry Morgan, the English took the lead. Morgan launched a series of devastating raids, culminating with the overland invasion and sack of Panama, on the Pacific coast of the isthmus, in 1671.

Morgan claimed to be unaware of the 1670 Treaty of Madrid, which had finally established peace between England and Spain. Called back to London, he got away with it. The King knighted him and the buccaneer returned to Jamaica to serve as governor. Sir Henry Morgan retired from piracy to become a sugar planter, eventually dying of drink in 1688. In Panama, the Spaniards rebuilt the old wooden port in stone, a few miles up the coast. During the rest of the 1670s, they felt secure on the Pacific shore, regarding the western coast as their private, secret ocean. The Caribbean, by contrast, swarmed with French and English freebooters, with Port Royal as their rowdy, lawless capital. The outlaw captains regularly pillaged Spanish ships and ports, from the Gulf of Mexico to the shoulder of South America.

One day, in early 1680, after a routine raid on the Portobelo silver depot on the Caribbean coast of the Isthmus of Panama, the Pacific coast became a target again. It began with a conversation between Jamaican buccaneers and their Native American allies, the Kuna Indians of Darien and the San Blas Archipelago. It ended with one of the most daring and exciting pirate adventures of all time. It is remarkably little known outside specialist circles. The general public seems to be aware of Morgan’s buccaneers and then leaps ahead to the Golden Age of Piracy, full of Stevensonian amputees, black flags and rum. However, for me, the generation of sea dogs between Morgan and Blackbeard has proved to be the most fascinating of all. Here, we catch glimpses of a great survivor who skirts along the margins of history for decades, linking the two periods with his legend. His exploits also influenced the subsequent course of politics, science, economics and literature.

I first became aware of this shadowy character recently, in a palm-lined square in a coastal resort three hundred miles north of Santiago, the Chilean capital. A plaque attached to the cathedral wall in La Serena proclaims, “The present building was constructed in stone on the site of the original cathedral destroyed by the English filibuster Bartholomew Sharp in 1680.” I had never heard of Sharp, but apparently most Chilean schoolchildren had. According to the phrase books, a version of his name even featured in a local saying: “El Charki llegó a Coquimbo” or “Sharky arrived in Coquimbo,” meaning that an unwelcome visitor had arrived out of the blue. Indeed, the buccaneers’ raid caused consternation. There had been virtually no English pirates on that coast since the days of Drake, Hawkins and Cavendish, in the previous century.

Back in London, I headed for the Greenwich Maritime Museum’s library and the National Archives in Kew, to discover more about Bartholomew Sharp. This East End cockney went to sea shortly after the Great Fire of London. As a young man, like many Port Royal buccaneers, Sharp probably participated in Morgan’s 1671 Panamanian invasion. We have no contemporary images of him, not even a physical description. He liked showing off his strength, though, by hurling spears from the rail of his ship, sending them crashing through the shells of turtles, in competitions with Moskito Indians. He was an inveterate gambler, often drunk, and he had a reputation for both occasional cowardice and remarkable navigational skills. He seems to have had an eye for exotic cabin boys. I wouldn’t be surprised if Johnny Depp modelled his effeminate cockney Captain Jack Sparrow on Sharp (Depp is rumoured to take his historical research seriously).

In late 1679, a small fleet, in which Sharp commanded a ship under the pirate ‘Admiral’ John Coxon, looted Portobelo. Each Caribbean raid was becoming more hazardous for ever lower rewards. Gold was rare. Less and less silver came out of the big mines in Peru and Mexico every year. More wealth stayed in the Spanish colonies, helping to strengthen local economies and, therefore, harbour fortifications. The buccaneers were no longer regarded as heroic defenders of the English islands. The Royal Navy began to hunt them. The rising class of sugar planters wished to maximise profits by cooperating with Spain instead of fighting. An early international capitalist consensus struggled to emerge. Morgan, now a planter too, had even hanged pirates at Gallows’ Point, to show how respectable he had become. However, plenty of wild places on land and sea remained for the buccaneers to hide in. Whereas Coxon’s fleet would have sailed openly from Port Royal in previous years, in 1679 it gathered in Morant Bay to keep a low profile.

To this day, the Pan American highway has not been completed in the Darien jungle of Panama. The Kuna Indians still jealously guard their autonomy along the San Blas coastline (see Neil Geraghty’s ‘Secret Islands of the Caribbean’ article in the September/October 2012 Dante Magazine). After the Portobelo raid, a Kuna war chief known as Captain Andreas offered to guide Coxon’s little army of three hundred men to a store of Spanish gold at Santa Maria, on an estuary that opened into the Pacific Ocean near Panama. After a gruelling march through the Darien jungle, they stormed Santa Maria, but the gold had already been removed to Panama.

From there, a bold captain called Richard Sawkins effectively took command and led the expedition into the Gulf of San Miguel. Firing at the Spanish ships from canoes during a bloody engagement within sight of the city, the buccaneers captured merchant vessels and occupied the nearby island of Taboga. Coxon was accused of cowardice for sitting out the battle. He led his crew back to Darien and the Caribbean shore in a huff. On Taboga, Sawkins was the first to advocate a cruise down the Pacific coast, to attack Arica, the port that served the mighty inland silver mine, Potosí. Known as “the mountain that eats men”, Potosí produced and minted most of the world’s silver pieces of eight. Two captured ships, now pirate ships, were now poised to break into the King of Spain’s private sea, straight to the source of his wealth. Before they could sail south, Sawkins was killed while storming a nearby harbour.

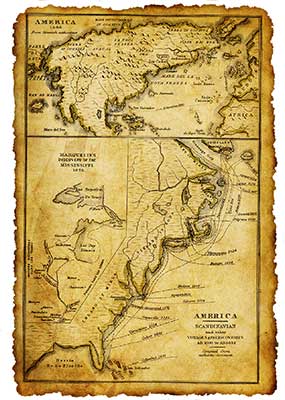

Old map of North American East Coast

It was Bartholomew Sharp’s moment. The men voted democratically for him to lead them, mainly because of his expertise as a “Sea Artist”. For the next two years, he cruised up and down the coast of South America, surviving bad weather, diseases, earthquakes, defeats and mutinies, to accumulate a fortune in stolen silver. Much of the loot found its way into Sharp’s possession during protracted games of dice with his crew. The unlucky gamblers on board became a constant source of discontent. They had endured great hardships only to be left penniless by their own captain. A high-stakes gambler’s spirit, reinforced by captured tobacco and alcohol, lay at the heart of piracy. A significant number of losers usually wished to continue raiding, while the winners became anxious to call it a day. Pirate ships were, in effect, floating, overcrowded, armed and drunken gambling dens. In the absence of females, cabin boys could change hands, on a roll of dice when the cash ran out. Eventually, sheer exhaustion decided the matter. It was time to go home, but where was home?

Returning was not easy. Sharp penetrated deep into the Pacific before steering southeast. During a brief landfall above the Straits of Magellan, he tried to ingratiate himself with the Stuart royal family by naming an island after King Charles’ brother, the Duke of York. He became the first English captain to ‘double’ Cape Horn, sailing from west to east. Passing Antarctic icebergs, he swung northeast, along the entire continental mass, into the middle of the Atlantic, before returning to the Caribbean. Meanwhile, Sharp’s depredations, in flagrant violation of the Treaty of Madrid, had caused a diplomatic uproar. In 1682, the Spanish ambassador in London succeeded in dragging Sharp before the Court of the Admiralty in Southwark, on capital charges of murder and piracy.

Like Morgan, Sharp got away with it. Unlike Morgan, he was not knighted, but was offered a captain’s commission in the Royal Navy. Charles II admired gamblers, and the buccaneer had an ace up his sleeve. While looting a ship, he had managed to seize a detailed compendium of sea charts, showing all the harbours from California to Chile, before the Spaniards could throw it overboard. If those early sailors were the astronauts of their time, the charts were comparable to today’s nuclear secrets. Sharp gave the king, who loved all things nautical, priceless naval intelligence. The Admiralty Court dismissed the Spanish ambassador’s case. It relied on the eyewitness testimony of mulatto cabin boys who had escaped from Sharp’s clutches. Nobody, the Admiralty said, could value the word of coloured slaves above that of a freeborn Englishman. The English ambassador was expelled from Madrid, but the pirate walked free.

Sharp never served in the Royal Navy. He gathered a crew to steal a French ship off Dungeness and resumed his plundering career. We catch glimpses of him in New England, Anguilla, Bermuda and finally, years later, in the Virgin Isles. The cockney captain never gave up his marauding, reputedly dying in the Danish castle on Saint Thomas in the 1690s. He had outlived the Stuart dynasty. As a result of his cruise, Darien and Panama, the gateway to the ‘Great South Sea’, became a target for English predators in the final decades of the seventeenth century. A desperate gaggle of pirates crossed into the Pacific after Sharp, with little success.

Shortly after the foundation of the Bank of England, modern speculative capitalism first displayed its irrational, destructive side when the South Sea Bubble burst. Speculators had been sold a bankrupt illusion of South Sea profits, originating with Sharp’s breakthrough. The British would have to push Chile into the War of the Pacific, during the nitrate boom of the late Victorian period, before London could make an obscene financial killing on that coast. Sharp’s priceless charts gathered dust. Spain’s last inbred Habsburg king died childless, sparking off a series of wars within Europe, which became a massive global conflict for world domination between Britain and France, all the way to Waterloo.

The death, in 1700, of the pitifully deformed King Carlos II heralded the end for the old buccaneers. They had always stolen from Spain. Now, a fresh breed of sea wolves attacked ships of all nations indiscriminately. The most successful of them all, Captain Roberts, changed his first name from John to Bartholomew in Sharp’s honour. He looted over four hundred vessels until his violent death in 1722, after a typically short, three-year career under the black flag. A new age, the so-called Enlightenment, was dawning. Here too, Sharp’s voyage was seminal. Surprisingly, his 1680 crew contained a group of talented writers with interests in cartography, botany, biology and anthropology. William Dampier, Basil Ringrose and Lionel Wafer, managed to scribble down their stories and observations between storms and battles, protecting the pages in bamboo tubes. They virtually constituted a piratical research team and press corps.

Dampier led a further expedition to Sharp’s refuge on a desert island in the Juan Fernandez archipelago, marooning the mutinous Alexander Selkirk. Recently, the Chilean government renamed it “Isla Robinson Crusoe” after Daniel Defoe’s groundbreaking novel, which was inspired by Selkirk’s ordeal. Charles Darwin cited Dampier’s notes about the natural world as an earlier influence on his own studies. Ringrose wrote the best account of the 1680 cruise and created remarkably accurate maps. The surgeon Wafer “went native” among the Kuna Indians, faithfully recording their customs alongside his adventures. Compared with any other ship full of sea-robbers, Sharp’s crew contained a remarkably literate and creative nucleus.

So, what remains today of the cockney mudlark who terrorised the Spanish Main, apart from garbled myths, a colloquial phrase, children’s stories and a plaque on a remote cathedral wall? The Coquimbo football team, at the site of Sharp’s anchorage near La Serena, taunt their local rivals by wearing pirate badges on their strip. Coastal bus lines are named after his buccaneers. In England, hardly anybody has heard of him. In my opinion, he deserves a statue in his native Stepney, but nobody knows what he looked like. The hustlers who dress up as Jack Sparrow on the South Bank will have to do.