Can Green Technology Save the Planet?

agosto 1, 2013

Modern-day Battle for Souls: Large-Scale Economic Development in Poor Countries

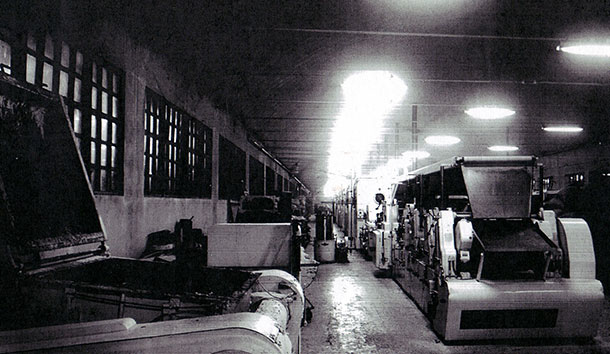

agosto 1, 2013The Doria story is one of strong traditions coupled with an eye to the changes and innovations of the future. That may be one reason why the aroma from the factory is said to signal a change in the weather. The products are made using the tried-and-true recipes that can be traced back to the 1800s. Yet, the company has moved, along with its workers, into the unfathomable changes brought by the 20th century – including women moving from their sphere in the home to taking their place in the workplace. Indeed Doria has been at the forefront of this change for several generations now.

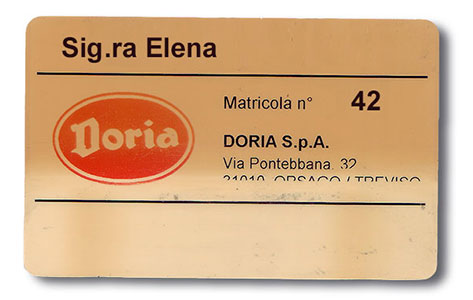

My rendezvous with Signora Elena takes place in the new restaurant-bar that Doria-Bauli have opened next door to the factory. “Wow!” she says as she looks around the building. “Look what they’ve done here!” She is clearly impressed with the job the new management has done. But as she catches sight of the old gate facing the road, her face lights up and she heaves a nostalgic sigh. “When I first walked through those gates I was a little girl in a skirt. We weren’t allowed to wear trousers in those days, you know. In a way I became a woman in there. How can you forget somewhere like that?” Signora Elena is now a cheerful grandmother, but she still has a twinkle in her eye as she remembers the good times she had working for the Doria-Bauli biscuit factory. Doria, in these parts, is much more than the story of a great industrial project. For many of the beautiful elderly ladies who once worked there, it represents their youth, their family, the place where they spent their lives – in short, their destiny.

“Times were different then,” Signora Elena says with a gentle smile, as we start our tour around the outside of the building. “The biscuit factory was our first job, and it wasn’t the easiest one either. It changed and shaped us, and our community; it’s what we still talk and think about most of the time. It’s incredible, really!”

Here, in the northeast – the economic backbone of Italy, a few kilometres from Venice – the Doria-Bauli plant is still a watchful presence. Our meeting marks the first time Signora Elena has come back to the plant since she retired in the late 1990s. I am privileged to be with her, and see her eyes open wide with amazement, and hear her trembling voice as she recalls her days on the cheese-cracker-biscuit line.

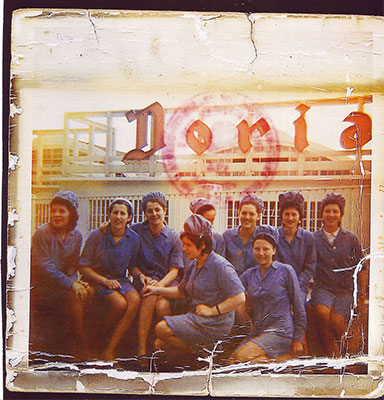

“Young men from the surrounding villages used to come to the factory gates after we finished our afternoon shift,” she remembers with amusement, “all dressed up and their hair all slicked back on their Lambrettas, hoping for the chance to meet one of ‘le tose del biscottificio’ – the biscuit factory lasses, as they called us. It just made the hard work on the pastry line a little bit more fun to do – all those love affairs to gossip about! That’s how I met my husband, you know! Just like many of the other girls too!” she recalls with a happy smile. However, it caused a bit of a scandal with those girls parading together in front of a whole lot of young lads – so much so, that going to work for the factory was seen as a challenge to the status quo.

For some time after the war, men and women were still very organically connected to the world they lived in. Electricity was scarce, and everyday life directly followed the rhythms of nature. So in industry and commerce during those times, the demarcation lines between the means of production, property and the workers were not so clear-cut. Signora Elena’s stories describe this world vividly: “The padrona, the owner’s wife, came from the nearby village, and she thought we were at the factory not just to work, but to learn as well. There wasn’t a day when she wouldn’t remind us of the times before Doria started, how she used to carry the freshly baked bread on her shoulders to sell at the local market. It’s stories like that that made us proud to be here!”

As I walk with Signora Elena round her old haunts, I can feel her mind drifting back to a past where work and life blended with each other more gracefully, when factory owner and worker were all part of the same story, the same success story. However, peering through the windows of the new Doria-Bauli factory building, we catch sight of the young girls who work there nowadays. When we meet up with them, I realise some things just haven’t changed – the way they talk and joke with Signora Elena, with that same twinkle in their eyes, only confirms what a good atmosphere there still is here. “It’s funny, isn’t it?” Signora Elena muses. “So many years have passed, and I can still see some of myself in those girls, even though the girls these days are much more emancipated. I think that in some ways it’s what life is like in that place, so close to home, but so far from it as well – that’s what gives this place its unique feel.”

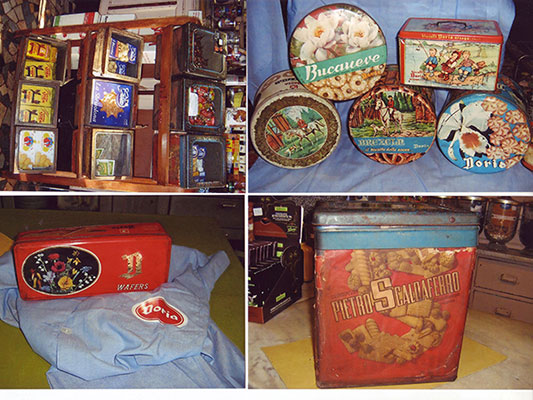

Gloria, Signora Elena’s niece who also works at the factory, joins us, “You know, on my first day at Doria, I had an amazing deja-vu! Aunt Elena had been telling me a lot about the biscottificio, and I remembered this story about the proving room.” “Oh yes!” Signora Elena says, as she throws me a smile and takes up the story. “The proving room over there next to the baking room was where, during the winter, the dough for all our products – biscuits, panettoni, cream crackers, you name it – needed to be kept warm. The owner’s son – what a lovely man he was! – wanted us trainees to make sure the stoves always had enough wood to keep the room warm. So we had to keep going out to the back of the building to get these logs. The thing is, winters in those days were extremely cold. One day, it had snowed so much we couldn’t get to the wood store; then, across the field, we saw the pig sties which were much easier to get to, with their fences all bright and sparkling in the snow. And so (here Signora Elena giggles, covering her mouth with her hand) we dragged some planks out from one of the fences, reckoning no one would notice. The next morning, we heard the owner complaining “Do you see that spot?” she tells me with the playful smile I have come to appreciate. “That’s where we used to collect the tins the biscuits were sold in. Way before cardboard packaging, you know, you had to return the tins to the factory so they could be cleaned and re-used. All this talk you hear nowadays about recycling! In those days, we recycled every thing, you just couldn’t afford to throw things away. And to think that then if a customer didn’t return their tins, they weren’t just fined; they were given a serious telling-off too!”

Outside, in the courtyard at the far end of the building, Signora Elena chuckles as she points at a shallow little crater in the middle of the courtyard: “That reminds me of a funny story. One day, this new girl comes in on her first day. She was put in charge of a large vat, boiling away, there in the middle. After work on our way home, when we asked her how she felt the day had gone, she got really upset. I asked her why; she’d had the easiest job going. ‘I thought I’d come here to make biscuits’, she sobbed, ‘and instead they go and make me cook animal feed!’ Then we all burst out laughing and joked about how innocent she was – of course she’d been put in charge of the glue-making; we would use any spilt flour to make glue to use in the packaging!”

As I walk with Signora Elena round her old haunts, I can feel her mind drifting back to a past where work and life blended with each other more gracefully, when factory owner and worker were all part of the same story, the same success story. However, peering through the windows of the new Doria-Bauli factory building, we catch sight of the young girls who work there nowadays. When we meet up with them, I realise some things just haven’t changed – the way they talk and joke with Signora Elena, with that same twinkle in their eyes, only confirms what a good atmosphere there still is here. “It’s funny, isn’t it?” Signora Elena muses. “So many years have passed, and I can still see some of myself in those girls, even though the girls these days are much more emancipated. I think that in some ways it’s what life is like in that place, so close to home, but so far from it as well – that’s what gives this place its unique feel.”

Gloria, Signora Elena’s niece who also works at the factory, joins us, “You know, on my first day at Doria, I had an amazing deja-vu! Aunt Elena had been telling me a lot about the biscottificio, and I remembered this story about the proving room.” “Oh yes!” Signora Elena says, as she throws me a smile and takes up the story. “The proving room over there next to the baking room was where, during the winter, the dough for all our products – biscuits, panettoni, cream crackers, you name it – needed to be kept warm. The owner’s son – what a lovely man he was! – wanted us trainees to make sure the stoves always had enough wood to keep the room warm. So we had to keep going out to the back of the building to get these logs. The thing is, winters in those days were extremely cold. One day, it had snowed so much we couldn’t get to the wood store; then, across the field, we saw the pig sties which were much easier to get to, with their fences all bright and sparkling in the snow. And so (here Signora Elena giggles, covering her mouth with her hand) we dragged some planks out from one of the fences, reckoning no one would notice. The next morning, we heard the owner complaining about the pigs that had got out during the night! I fell dead silent with fear when I heard that,” said Signora Elena looking a bit embarrassed as she relives her story. I am intrigued by the way certain little things in life can make so much sense, even through the mirror of generations. Doria is not only an institution here – a model one – and a place to go when looking for a job, it has also shaped the way people live here, setting a trend and an example to all. Even though people can feel the bitter winds of the economic crisis blowing around them, there is a relaxed atmosphere at Doria’s core. Perhaps this magical biscuit factory is not as jolly as Signora Elena and Gloria have portrayed it, but there is something unique in the air. Factory and village are at one with each other, touching each other’s hearts.

For Italians, Doria cheese crackers and biscuits have such a unique taste and texture that they have become a tradition. And as with every good tradition, Doria sticks to the tried and true – it uses the original recipes its founder created. Today, as I write this in a local bar, I wonder whether there are still places like this left, other places where you can find people working in harmony with their environment as effortlessly as you find at Doria. Suddenly, on the wind blowing down from the Alps, I smell the aroma of freshly baked biscuits. Two locals come into the bar and greet the owner, who just asks “Solito apertivo signori?” (The usual, gentlemen?) The two nod and then start chatting. “Can you smell the Doria biscuits? The weather’s about to change again,” they remark, as they sip on their glass of prosecco and nibble on a cheese cracker – a Doria-Bauli cheese cracker, of course! Some traditions are so strong round here, nothing will change them.