Back to the Future as Bands Re-form, Go Green

agosto 1, 2013

Mission statement by the editors

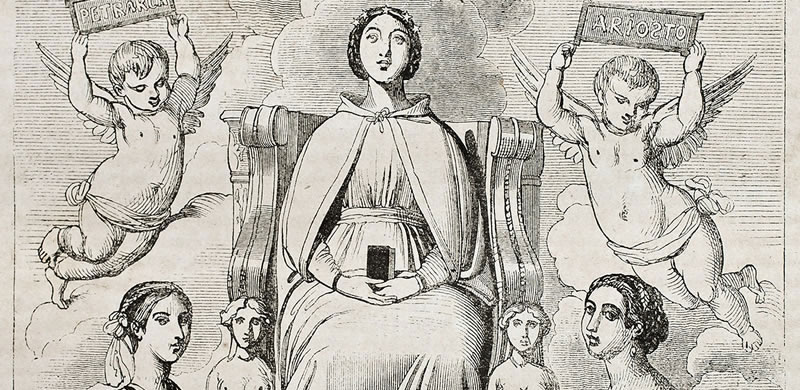

octubre 1, 2013“Men have hitherto treated women like birds which have strayed down to them from the heights; as something more delicate, more fragile, more savage, stranger, sweeter, soulful – but as something which has to be caged up so that it shall not fly away”

-Friedrich Nietzsche

“I am no bird; and no net ensnares me: I am a free human being with an independent will”

– Charlotte Brontë

One Man’s Inadequate Meditation in Praise of and in Solidarity with Women

As a man I have never understood the appeal of life lived exclusively or even primarily in the company of other men as the most preferred and natural order of things. In any circumstance or setting, a life without women would be a barren and bleak existence for the soul. I have never liked segregation of the sexes (any more than I have apartheid between any human beings for any reason) and I would not do well in a monastery nor amongst one of the remaining primitive tribal societies, where nomadic male herdsmen, preindustrial farmers or hunter-gatherers who have escaped modernity’s encroachment are still taught the most rigid, arcane masculine values and imperatives, little removed from the days of the cave. This dark tradition of man as absolute overlord over woman, has its cultural variations, of course, in a geography as wide-ranging as the Pan-Sahel region to the Amazon Basin, the Anatolian Plain to the mountain ranges of Central Asia. Yet the most extreme patriarchies of this sort often share a common gospel.

It is an unfathomable distortion based on the enduring prejudice that all women are inherently inferior to men in all human endeavours and otherwise should accept their lot as subservient and subjugated beings, fit only as chattel for men, to bear their children, fetch wood and water, tend to ‘women’s work’, give them sexual pleasure and obey unquestioningly, upon ultimate pain of death or banishment. It implies just as clearly that women’s thinking and aspirations are petty and trivial, worthy of little consideration or voice and certainly no education to cultivate their faculties. Little wonder these women are routinely bought and sold in exchange for livestock, as a mere commodity. This oppression is anchored in codes of morality that are usually the construct solely of men, under the equally abominable assumption – where sex and eros are concerned – that women are inherently wicked, less virtuous and lacking in sufficient propriety unless this is routinely and strictly policed and harshly enforced by men. Venerable cultural practices and religion strengthen it and violence is its guarantor.

Under its false premise, even a promiscuous man is judged virile, whereas a woman is culpable of any rape she suffers, having provoked it as temptress. Any woman who expresses any hint of choosing her own partner freely, in accordance with her own wishes and not those dictated to her and who might presume to be sexually and emotionally liberated, is judged a harlot. It is nothing less than Puritanism and is inherently misogynistic by design, objectifying and denying women their humanity, their will and identity. In an era of political correctness we can be easily dismissive and tolerant of these norms, under the hollow notion of respect for “traditional societies” and cultural preservation, as if we were looking at a museum exhibit instead of human lives, but there is nothing romantically rustic or noble about it. I can think of nothing more stultifying and crushing to both spiritual and intellectual well-being – and not just women’s – than perpetual existence in an all-male enclave or neanderthal patriarchy.

Although such a limited human reality and cultural restriction is (perhaps) happily anathema to the first world existence I lead as an inhabitant of a larger global civilisation, I remain astounded at how many facets of such backward thinking and value judgments, which can only be regarded as medieval, still permeate our supposedly more evolved societies. Their insidious presence remains disguised as something else: like the epidemic of sexual violence and bondage of women that has never gone away. Women have become heads of state, generals in armies, CEOs in the boardroom and vaulted to prominence in every possible facet of society and culture from arts and letters to the sciences, indeed any profession or vocation one could name. Yet the restrictions, discrimination, abuse, all manner of barriers impeding their progress and equality, invisible and overt, still remain, often codified by law and still accepted as the justice of divine will. If we consider the larger Judeo-Christian-Islamic tradition alone, women have largely not achieved equality with men as members of the clergy nor in the way holy scripture values them. Just ask Pope Francis, the Patriarch of the Russian Orthodox Church or the Chief Rabbi of Litvak Orthodox Judaism whether women may now lead congregations. A Wahhabi imam would be, if anything, even more scornful of the idea. And, for that matter, how long has it been since a Bodhisattva took female form? At least the descendants of the Incas in the Andean altiplano still revere, Pacha Mama, Mother Earth, as their most sacred deity. Oh, but wait; they’re pagans, alas -what do they know? The Almighty, who cast us all in ‘his’ image, otherwise remains an exclusively male figure with entirely male prerogatives – so not much equality under heaven either. And the morality police is not just present in Iran and Saudi Arabia or the Taliban-controlled mud villages of Pakistan’s tribal territories, not merely confined to the most intransigent strands running through the arch conservative veins of Islam. It cuts across cultures and traditions from India to Russia and indeed America, every single time a woman who falls prey to sexual assault is perceived the instigator and not the victim. ‘She dressed provocatively. She should have known better.’ Not least. it is present in the halls of the US Congress and in state legislatures throughout the country as Senators and Representatives keep trying to legislate away a woman’s right to choose what she may do with the reproductive functions of her own body. Much of the Middle East and North Africa finds itself in the midst of ongoing revolutions for greater democratisation and equality in the whole of society. Women have been at the vanguard of this epic change-in-themaking throughout. Nothing could tarnish the outcry for liberation more than the epidemic of gang rapes taking place in Tahrir Square. And it is not only secularist men in the greater Muslim sphere who take to the streets demanding change; many are religious traditionalists demanding the adoption of Sharia law, hoping the wheel of civilisation will rotate counter-clockwise. They will have no problem with women not being allowed to drive, deprived of higher education, being stoned for adultery, whipped for being rape victims or ritually murdered in honour killings where their offences in shaming their families include simply dancing in the rain.

I don’t understand any of it and I never will, no matter which cultural, historical, religious or moral rationale is forced upon women to keep them in their place, to violate them, to deny them all that is rightfully theirs, just as it is mine, namely, to be free human beings in a state of equality. My late mother, Rukmini Sukarno would concur. In the span of my life I have seldom come across a more potent human being and I count myself fortunate to have been her son, despite what I can diplomatically best describe as quite literally her operatic character, as much Madam Butterfly as Aida. She remains in my memory the most indomitable, cultured, artistically gifted giant of a personality in my experience of strong women, who possessed a fierce intelligence, a driving willpower, as vast reserves of moral courage and an ardent independence of mind, as I have ever beheld.

At the apex of her career she was one of the premier sopranos to ever grace the stage in the finest opera houses in Europe in the 1960s. She had left Indonesia on her own at age twelve to study at the famed Academia di Santa Cecilia conservatory in Rome. She would go on to win, at the age of 19, the Concorso Nazionale di Bel Canto, Italy’s most prestigious national competition for opera singers. She was above all a live performer, her recordings are sadly few in number but I will never forget seeing her in her many triumphs, the audience roaring its approval with standing ovations, the stage covered in roses, from the San Carlo in Naples to the Liceu in Barcelona. It was no accident that my mother was compared to Maria Callas. Though barely five feet tall, the fiery-tempered diva, fluent in eight languages, daughter of Indonesia’s founding president, was no mere mortal.

One of my favourite stories about her is when a would-be male assailant in Rome had the poor tactical judgment to try to both rob her and molest her, when he judged her a ripe target in a parking lot. He miscalculated terribly, and ended up being led by my mother to the carabinieri station for processing, where she brought him bruised and battered, yelping, by his hair. No man could best my mother, much less win in a dastardly surprise attack. My mother was devoted to my late father, the Hollywood and Broadway actor, Frank Latimore, right to the end, but there was no doubt as to who ruled the roost in my childhood home. My father loved her deeply and was just as much in awe of her. He had fallen in love with her at first sight and never regretted his choice. Their ashes today nurture the same apple tree in a rural corner of New England according to her last wishes.

I will admit I am biased in favour of women, not just for their beauty, but for all that is inimitable about them, all that makes them women. Far more eloquent pens than mine have addressed this – from Catullus to John Donne – so I will leave those flowers to them. I will admit too that, where possible, I will seek out the company of women in preference to men. Not that I don’t have male companions who, as an only child, I have come to think of as brothers. But if that analogy holds, I must report I have more adopted sisters than brothers, which the vicissitudes of life have placed in my path for me to befriend and be enriched by. Never have I wished to be their master.

I have had two professions in my adult life, as a working cowboy and as a journalist. I do not for a moment forget the men who have made my journey a better one, who have shared my trials, my hardships and my achievements. I love them too. But if I think on my days as a buckaroo, my closest friends were two cowgirls, who worked in the saddle just as the men did and were every bit as tough, each a better horsewoman than any I ever saw sit a horse as a top hand in the corral, or out of it.

It also figures that many of my closest colleagues throughout my career in journalism have been women rather than men. My mentor in clandestine war reportage in the Caucasus was a woman. The finest field producer and investigative journalist I’ve ever teamed up with, when in Iraq, became like a sister. Without any equivocation either, the most capable reporter I trained in Afghanistan was a woman. And the most fearless, resourceful, tenacious and human rights investigator in war zones that I’ve ever come across is also an utterly unbowed woman.

It’s hard to have pleasant memories of war, but the time I spent talking with a jovial young woman, a US Army GI, in a tiny concrete bomb shelter which could barely contain us both in the midst of a Taliban rocket attack in Afghanistan is such a memory for me. She was possessed as much of all the feminine graces as her bearing was unmistakably military and composed; her girlish laugh and infectious smile was as timeless and beautiful as her M-16 rifle was lethal in her competent and confident soldier’s hands. One of these days more men will see what I readily saw in her, recognise that her dichotomy is nothing strange, her qualities not mutually exclusive, will not feel threatened by her and instead feel proud of her and grant her the respect she is due as a fellow human being. Such recognition may take a while to become widespread. And until it does happen, my place, and I believe every man’s place, if we are men worthy of the name, is to stand next to her, because we are only strong men when we do, and when we don’t, we are invariably weaker for it.