Nonno Panda TALES 13

diciembre 10, 2013

In the Soap Kitchen

diciembre 13, 2013With an estimated 65,000 students graduating from design and creative art courses in the UK this year, how many will succeed in securing a coveted position in their preferred occupation? It is a question posed by academics and industry alike year after year; yet with no sign of falling enrolments, how can we possibly continue to deliver an educational model that will produce designers capable of meeting all the demands industry makes of them?

For a subject in its relative infancy and one that has at times lagged behind the emerging practices within industry, higher creative education needs to be all things to all people. It can no longer specialise in one defined area of expertise while ignoring outside influences or collaborations.

A university course of study should be, without doubt, a place to experiment, to develop new ideas and ways of thinking about how we position ourselves in the world and the responses we want in return. Those three or four precious years must be used to encourage creativity, pose questions and increase resourcefulness, while at the same time raising aspirations to produce effective communicators and contributors to society.

These are all laudable and admirable goals, though when you are faced with clients who have an expectation to meet budgets and hit deadlines, circumstances can seem very different. An understanding of where the client’s expectations lie and of how to manage them is of paramount importance in bridging the gap between expressive discourse and commercial reality. We need designers whose grasp of commercial success is as fine-tuned as their designs.

In a survey carried out in 1999, entitled Destinations and Reflections1, two thousand graduates were questioned about their working habits post-graduation. Many of those participating considered their skills in basic areas such as writing, numeracy, teamwork and self-promotion to be lacking or under-developed. Course content was at the root of these issues, with many degrees devoid of business and professional studies modules. This meant that a generation of designers were left floundering and unprepared to meet the transition between study and employment.

The recent global recession and economic uncertainty have only helped to compound the situation, as students find themselves without full-time or guaranteed employment. Creative graduates often take longer to establish themselves within a defined career path, but when even contract or temporary assignments vanish, many are left with little option but to develop an entrepreneurial approach to their work. It becomes obvious that the only route to survival is collaboration and invention between industries, which on the face of it, are the least likely of partners.

In response to the study results, the British Government’s Department for Culture, Media and Sport made a statement proclaiming:

“We will do more to understand and analyse the contribution of our creative universities. We will explain the range of talent and skills they require and seek to ensure that all those who have talent, whatever their background, can make a career in the creative industries” (DCMS, 2008)

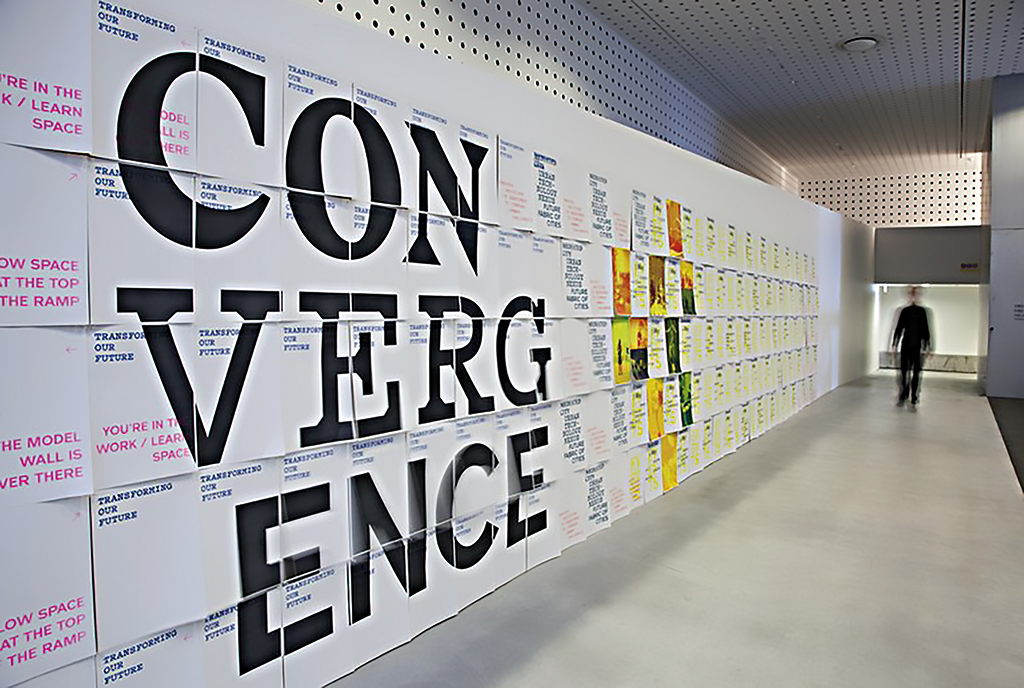

In consequence, universities now actively seek out business opportunities for their students to ensure that the courses on offer and developmental research undertaken meet with the changing nature of industry. Design modules are being included with MBA and business-school curricula and integrated into science and engineering courses. Collaboration is even actively encouraged within the university’s own departments, by way of emphasising the necessity for a multidisciplinary approach.

It is not only designers who must look outside of their own worlds, but clients, too, need to be educated in the language of design and how it can be of benefit to their business. How many times has community architecture or artwork been derided and criticised as a waste of public money? Those who are responsible for commissioning also need to stretch themselves and collaborate where necessary, rather than acting out the role of the grand patron. We must all be equipped with the necessary skills to negotiate and comprehend the made world. Maybe ‘design’ as a subject needs to be taught at a much earlier stage and included within the school curriculum. The UK has a rich creative history that informs current thinking as well as a diverse story to tell in bringing design alive. Historically, design education has been provided via one of two methods: Art & Design or Design and Technology. When introduced in 1988, it was hoped that the latter approach would engender a generation of pupils who could bring their experiences of learning from other areas and use these to engage in the design process. The Department for Education expected that the subject would enhance citizenship, motivate critical appreciation of the made world, and build on an innate human tendency to create and improve itself, helping to inspire enthusiasm for manufacturing and technically skilled occupations – both of which remain industries that desperately need stimulus to help growth, following their demise in the UK under a staunchly service-focused Conservative government.

Fighting back against this tendency, The Sorrell Foundation, created in 1989, aims to inspire creativity in young people and improve the quality of life through good design. Over twenty years later, it allows users to experience control and explore what decisions need to be made for the greater good of their communities. Not all of these decisions will be made by the designer so it is important that we create a generation of people who can provide critical appreciation, as well as build a societal infrastructure of public understanding, required to sustain design. By turning people on to the subject at an earlier stage, the aspirations of making them more alert to design and heighten their appreciations would surely be realised.

In short, what is needed now is some clear, joined-up thinking with definitive leadership from government to ensure that the collaborative process is put in place as early as possible. The school environment provides a natural forum for engaging people while they are young enough to approach it with an open mind and at a time when working on projects with external collaborative professionals often forms part of a student’s life. Museums and galleries are widely consulted, both as a source of knowledge and inspiration. Extending that process throughout one’s academic career allows for greater exposure to the wide-ranging possibilities of commissions with or on behalf of public authority thereafter. This widens the scope for the designer to create something different to their normative output and working methods, the results of which can often be unexpected to both the maker and the funder.

It is not a one-sided equation however with the commissioning body reaping the rewards of being seen as a progressive centre of excellence. Recognition brings with it multiple benefits, not least financial. And in a post-recession world, cultural institutions need to find and tap into all possible revenue streams.

The valuable cross-fertilisation of education and industry and the often lengthy relationships established throughout this process cannot – and should not -be underestimated. The blurring of traditional lines and boundaries will give rise to a new way of thinking from both the perspective of viewer and designer, neither of which should be held in higher regard, one above the other, but merely thought of as equals in a process of integrated thinking and connection.

1Blackwell A and Harvey L (1999) Destinations and Reflections: Careers of British Art, Craft and Design Graduates, CRQ, UCE.