SAILING THE CRUEL SEA?

agosto 1, 2014

Who Are The Devils These Days?

agosto 16, 2014How do you write about reading? How do you do it without sounding either facetious or pretentious? By being slightly confessional, more personal and less objective? Mario Moniz Barreto explores the Proustian memories of reading, the aesthetics of independent bookshops and the impact of e-books.

It may just about be one of my oldest memories, namely, being gently scolded by my mother for being ‘caught’ in the book-lined living room watching something silly on a TV that had been temporarily placed there. Her words underlining the fact that I was wasting my time and ‘How could I?’ and her (maybe somewhat exaggerated) sense of disappointment as she theatrically waved her arm towards the wall-to-wall bookcases are an ever-present memory. Had Mother been a poet she could have scolded me as Belloc did:

Child! do not throw this book about!

Refrain from the unholy pleasure

Of cutting all the pictures out!

Preserve it as your chiefest treasure.

.

Child, have you never heard it said

That you are heir to all the ages?

Why, then, your hands were never made

To tear these beautiful thick pages!

Maybe the more recent memory of Mother recounting how, in her halcyon days of a colonial Mozambique, lounging in the Maputo Cardoso Hotel pool looking out over the Indian Ocean, she got chatting with an older American tourist who introduced her to the poetry of Omar Khayyam – boy, they certainly had classier chat-up lines back in the early sixties!. This was her probably taking time out from a visit to her communist freemason Grandfather who ran a newspaper called The Emancipator with what was one of Sub-Saharan Africa’s first culture supplement, The Itinerary, and who had his library open to anyone who wanted to read. A plaque hung above the door to the reading room with the following words hammered onto it: «People’s House».

Another strong family recollection in our wandering days between Europe, Africa and Asia is the image of a few shelves of black leather, gold-embossed books, ever present wherever we were. These books were, according to Father, who had his initials (JMDMB) engraved on them, part of who he was, so that he and they were never parted. I would link all of these overpowering vignettes together with the purposeful conversations, guidance and even sometimes set readings my siblings and I had (after which we would have to explain in our own words what it was we had just read) to a life long love, verging on an addiction, of books, owning them and reading them. One might even say, as Foucault wrote regarding his childhood:

«J’évoluais dans un milieu dans lequel la règle de l’existence, la règle de promotion était dans le savoir; en savoir un peu plus que l’autre, être un peu meilleur en classe, j’imagine même mieux sucer son biberon qu’un autre.»

.

(“I grew up in a world whose rationale and laws of advancement were based on knowledge – knowing a little bit more than the next person, being a bit better at school and, I expect, knowing how to suck on my baby’s bottle better than anyone else”. Tr. PR)

A quotation that could easily have been uttered by my Father.

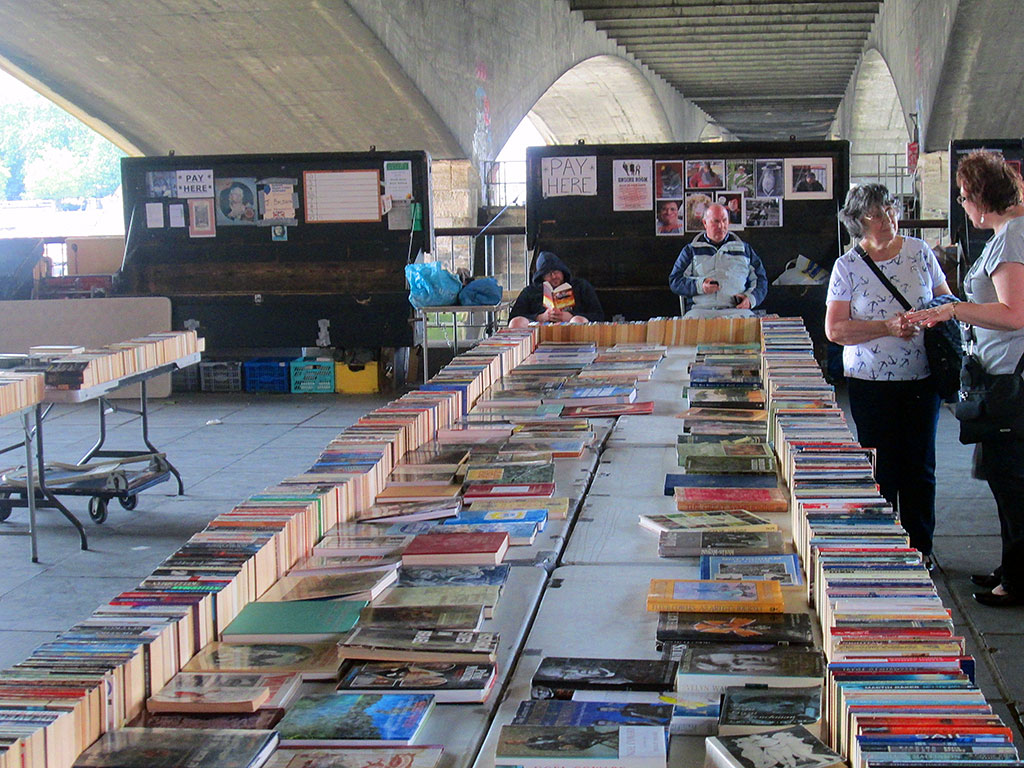

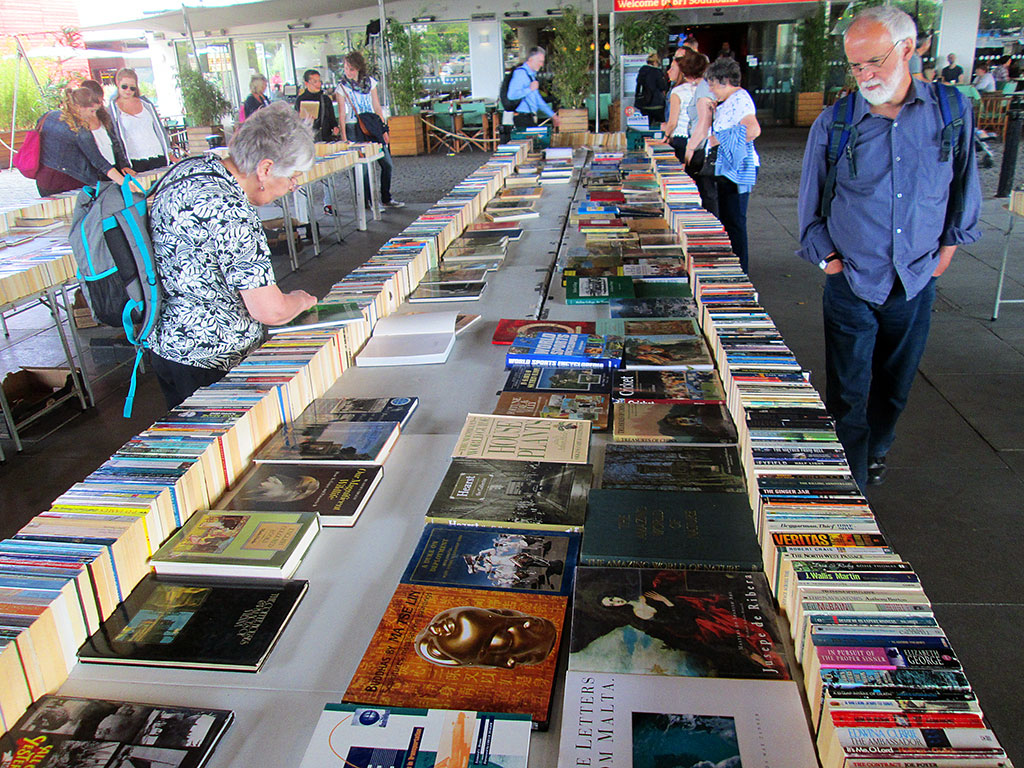

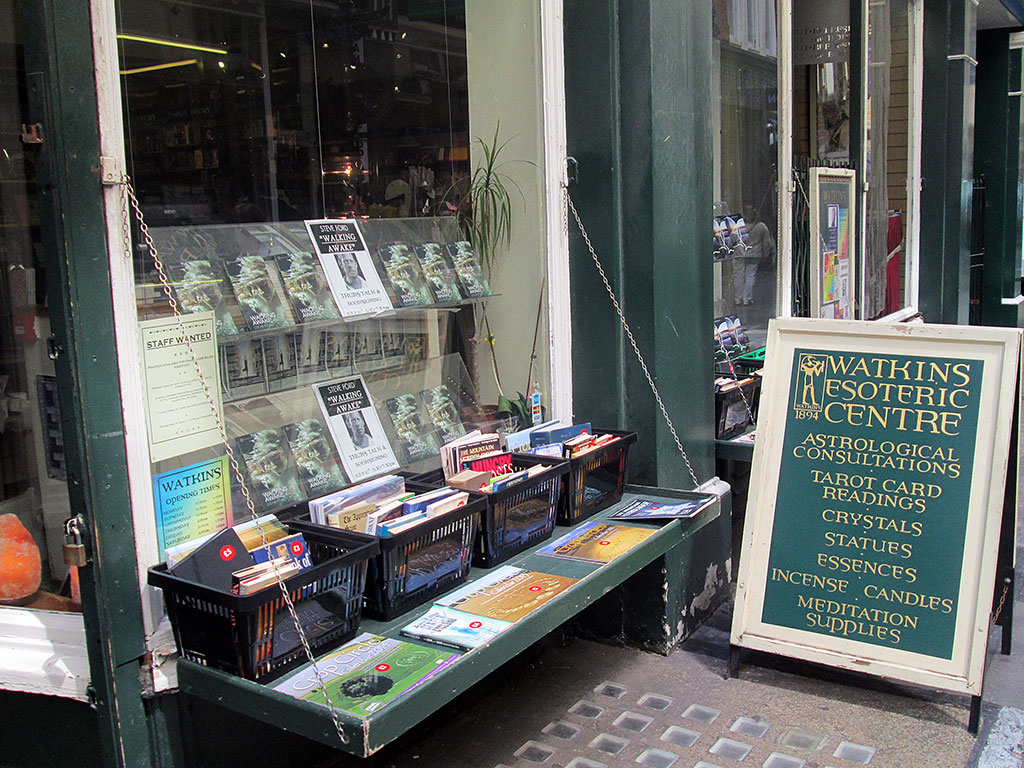

For the love of bookshops and the ghosts of books

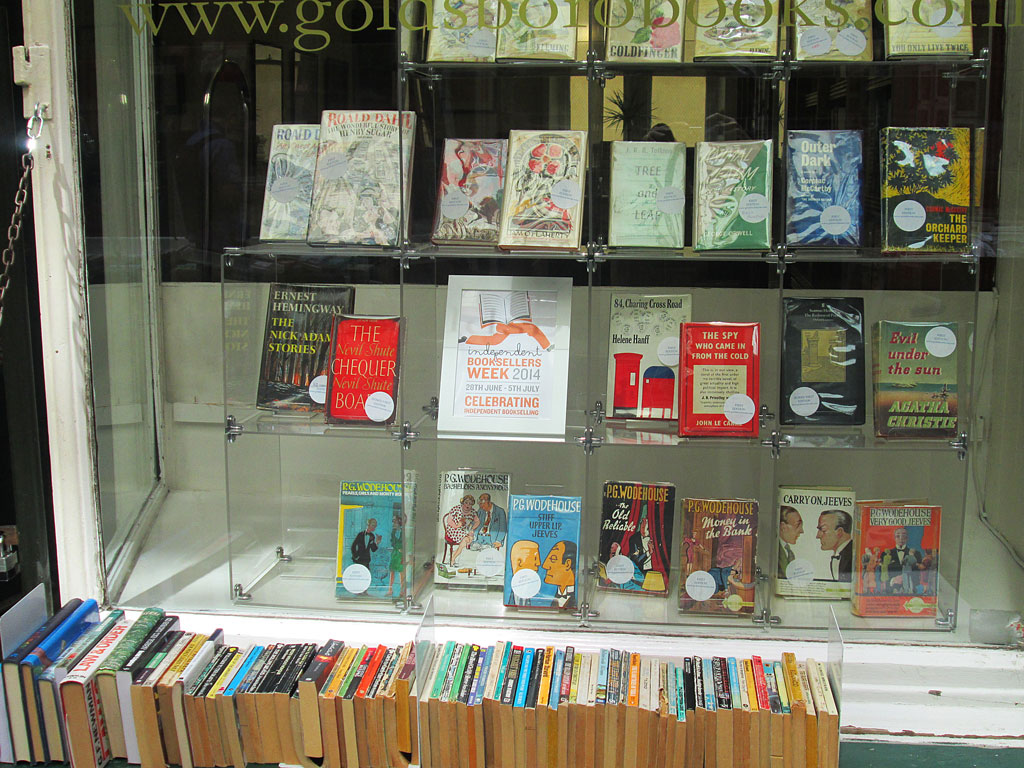

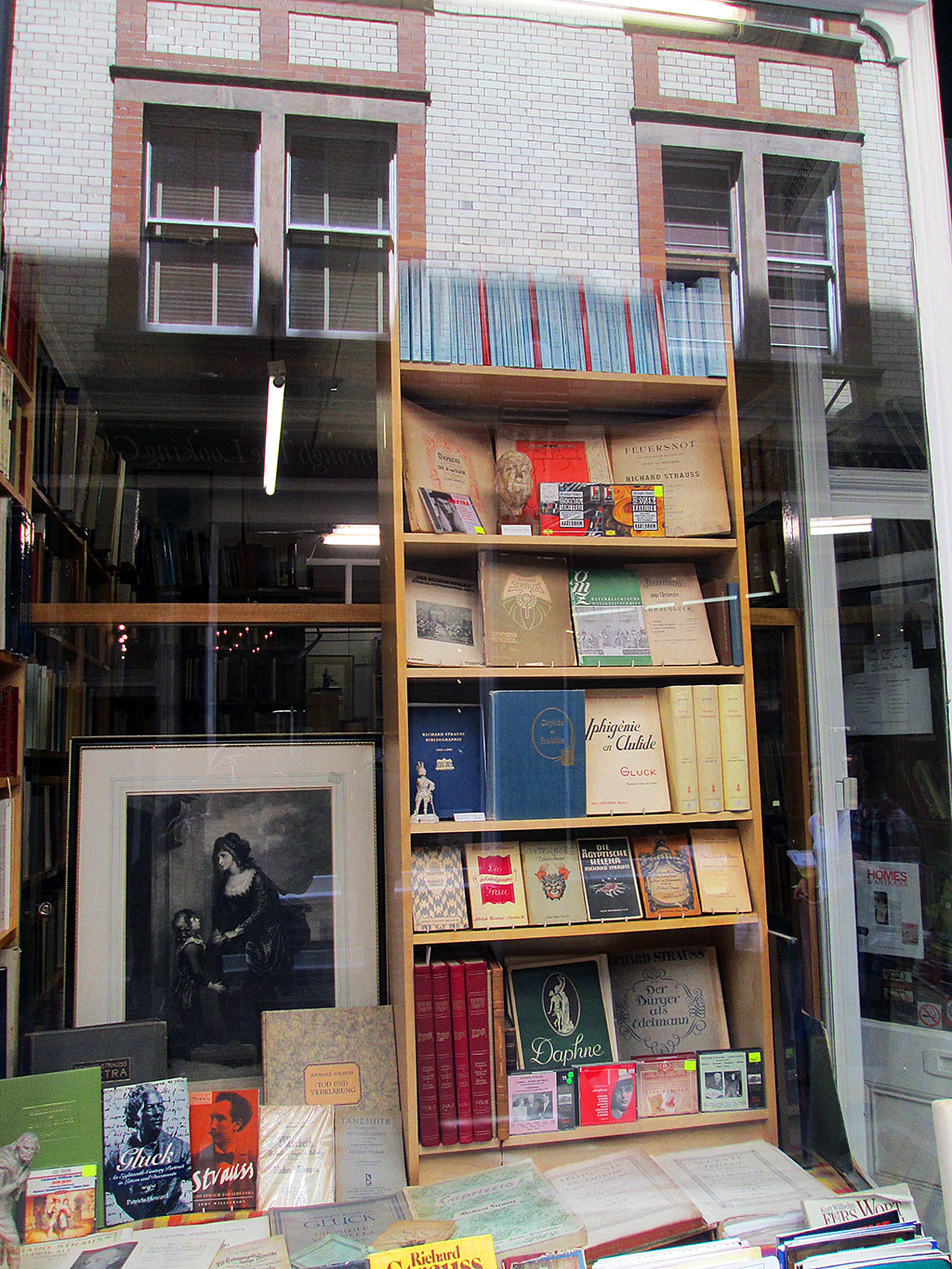

This is why, when travelling, I find myself equally drawn to the local bookshops as I do to the town’s cathedral. From Warsaw’s still incipiently gentrified ‘Nowi Swiat’ where bookshops still display some less commercial works by Kant or other great thinkers, as if they were hot-off-the-press sensations; to the more homogenised London, where no visit is complete without some walks snaking around Charing Cross Road and environs to check second hand books and, naturally, the re-located Foyles. Maybe even a foray into Piccadilly’s huge temple of books, formerly occupied by Daks Simpson, presently Waterstones beautiful Art Déco, if way too commercial, home, or to the somewhat crooked little Chelsea bookshop, John Sandoe’s, tucked into one of the King’s Road side streets. Or from Lello (voted one of the most beautiful bookshops in the world) in Oporto, to Tropismes located inside the Royal Galleries in central Brussels. Or from the New York’s Village based Three Lives bookstore, to the so many other establishments that strive for a degree of singularity in order to differentiate themselves from the rising bookshop chains where we stand a much slimmer chance of being positively surprised at finding something we didn’t know we were looking for. Knowing these places, exploring their bookshelves, talking to the assistants, throwing at them challenging requests meant that, even if I was not getting a feel for the entire city I was, at least, getting a grasp of what made that neighbourhood tick, or, in this case, it was reading.

I would argue that what people are reading is as much a sign of how developed any given Western state is as the state of its hospitals or schools – from the more hermetic or challenging authors to the ‘blockbuster-soon-to-become-movies’ paperbacks. For the books we choose to read at any given time reveal our interests as well as our needs or weaknesses.

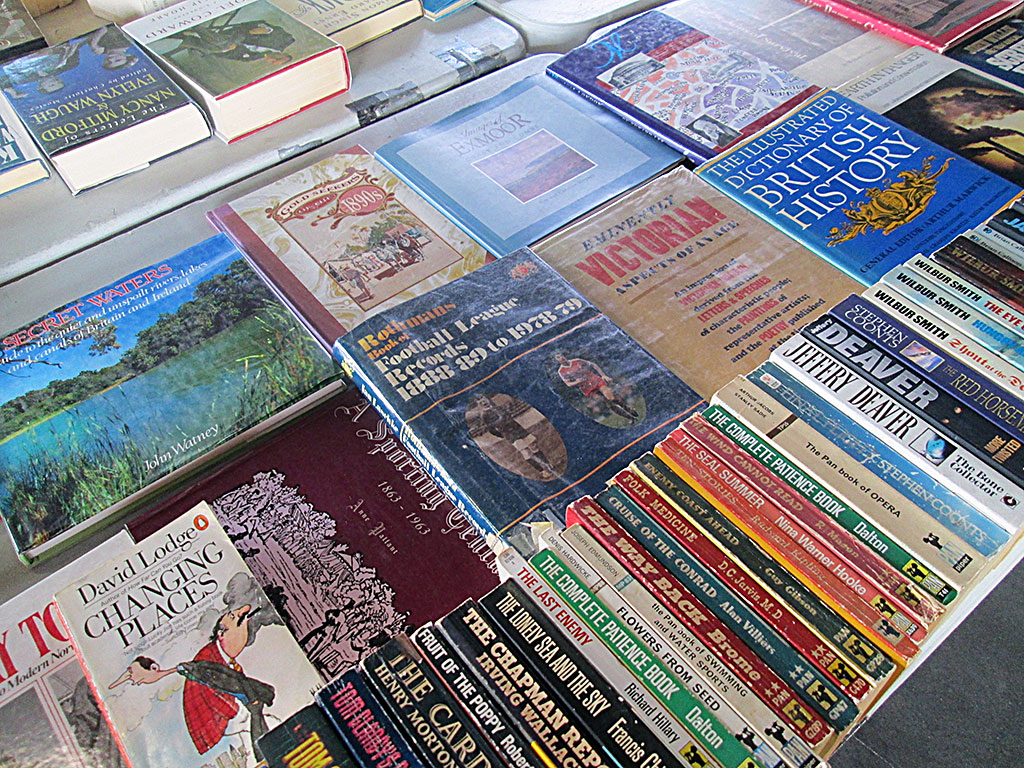

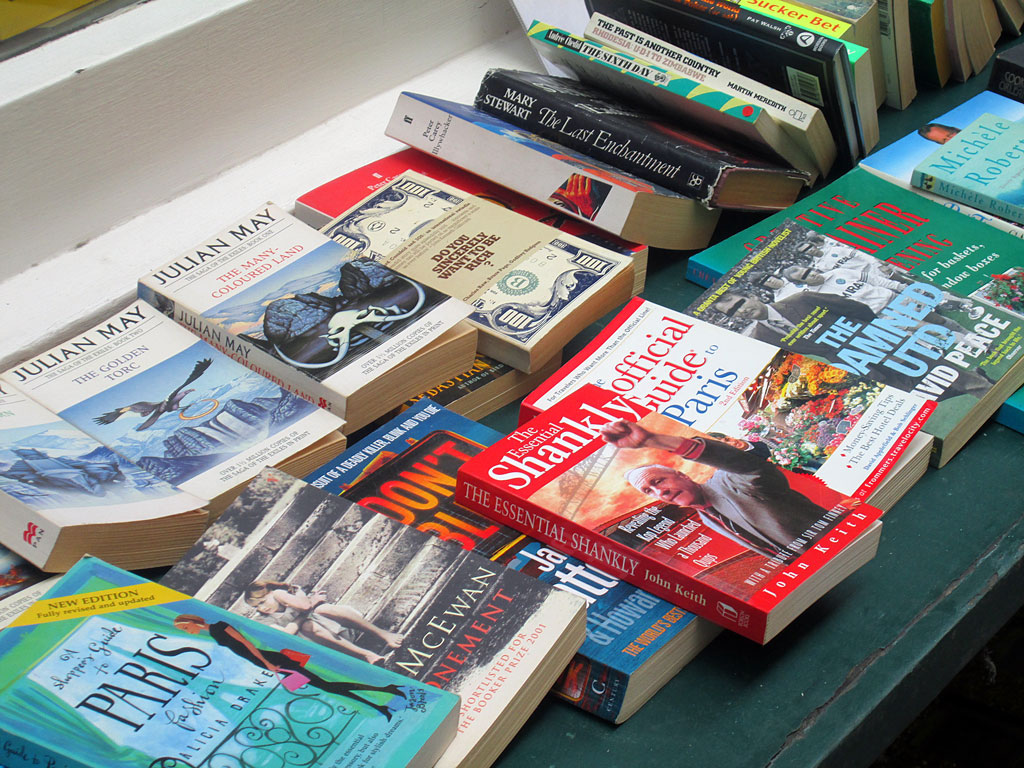

The love of the bookshop, of the singular ones, of the hidden, alternative, even secretive ones, where patrons may be as eccentric as some of the titles you encounter within, has – at least, to me – logical consequence; namely, that the books I buy in these places become in a way linked to them. And so books represent not only what they are about, but also where they were acquired. Naturally, for me, they also embody in an almost animistic way, where or how I read them.

For example, “Buddenbrooks: The Decline of a Family” by Thomas Mann is not only a grey windswept novel about the four generation cycle most families are supposed to go through (similar to boom and bust), but every time I think of it or it gets mentioned, I am reminded of the last days of a dying summer just before university finally started and I was allowed to stay on alone in a family beach house on the Algarve. So, in other words Buddenbrooks has become to me synonymous with becoming an adult. Whenever I think of childhood in the Far East I think of Emilio Salgari and his Maracaibo Corsair and Malabar Sandokan based novels. Without fail, once the typhoon season started I would sneak onto to the top floor terrace of our house on a promontory overlooking the South China Pearl River estuary in Macau, and I would imagine the pirate ships somehow materialising, out to reclaim the territory that had once been theirs.

So books, yes, are what they are about, but to me and, I suspect, to other people equally smitten with them, they are also somehow the places where they were bought/acquired from, where and how we read them.

The other dimension books take on is that they become symbols for us of what the other is saying about himself. Proust remarked that he didn’t know English, but that he knew Ruskin. That Victorian writer became for him the embodiment of what he thought of, or how he saw, England. This is why, to this day, Saint Petersburg has a constant throng of visitors retracing the delirious steps that Dostoyevsky’s Raskolnikov took in Crime and Punishment. Or why we keep expecting Kafka to come out of one of central Prague’s alleyways, or for Fernando Pessoa to quickly finish his drink in one of his Baixa cafés in Lisbon that still survive to this day. To the extent that some modernists can argue a book is also the result of the circumstances of his author and his author’s life.

The E-book, the selfish reader and the tiny living space

What you are reading, what you feel about what you are reading and the way friends, or even strangers observe what you are reading can be an inspiration, or, in cases of unhappy reading experiences, a word of caution.

This leads us to one of this age’s greatest tragedies, even if ‘only’ from an entirely voyeuristic or “show off” point of view, depending on whether you are the reader or the onlooker. The tragedy I allude to is the appearance and dissemination of the e-book. Until the manufacturers/accessorisers come up with some sort of changing cover to match what you are reading, the hotel swimming pool loungers or the crammed underground seats will no longer give us the empiric feel of what are the current book publishing success stories, as they used to when you were able to survey what people were immersing themselves into from a book cover survey.

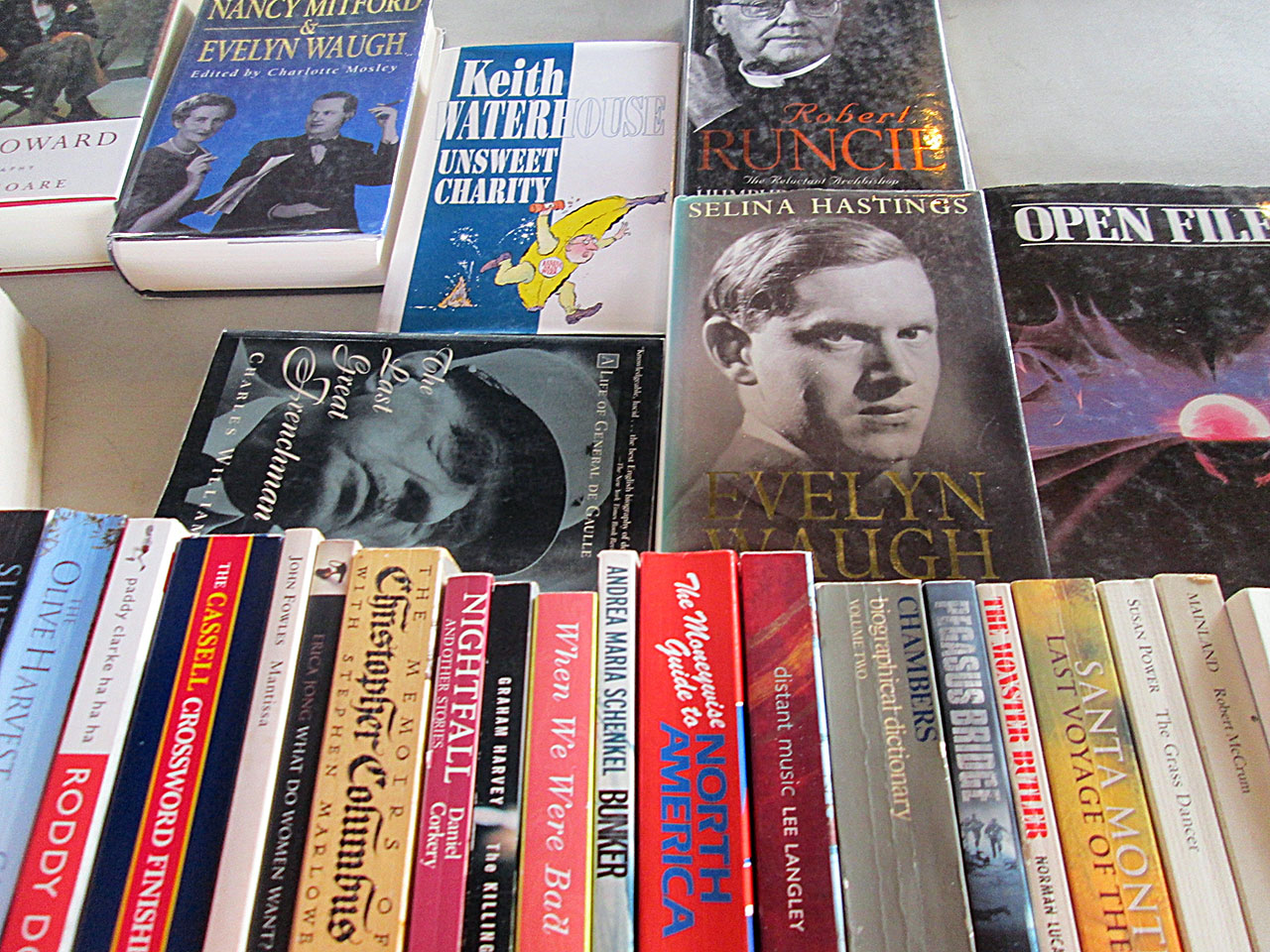

Who doesn’t recall the Helen Fielding smudge, or the proud or embarrassed Harry Potter reader, according to whether it was the children’s or adult’s edition they were reading on the underground and commuter trains? Trashy lit reading has never been as guilt-free in the eyes of others as today. In a way the plain cover e-book has made reading a rather more selfish act than what we were used to – maybe even as selfish as back in the day when books were available only to the wealthy and educated few. The only identifiable, worthy even, advantage of the e-book (from a reader’s perspective) may just about be the uncluttering effect it has, or will have, in many tiny to minuscule city households. Maybe I should mention that after the more or less pre-ordained books in my parents’ or grandparents’ homes, my present experience of books tends to be a rather less organised library one – books accumulated in neat second row piles, without completely covering the first row ones, then, without realising when, the first row disappeared from sight obscured by later buys. I now have to rely on my not so fool-proof memory of what I have when scavenging for some title. Lately any nook, slit or slot will suddenly find itself with a rather less than tidy pile of books. Whenever I look at this apparent chaos I think I should get rid of some impulse buys, which, together with some disappointing books and some outdated ones, would free precious space for new – and one would hope – more carefully selected acquisitions.

The revenge of the intellectual?

No rambling on the subject of books and the love of reading would be complete, however, without noting how the ramblings even in the more successful bookshops have been changing for the better recently. After the excessive marketing of books as commodities, using techniques normally employed to sell soft drinks and toilet paper on books, one has witnessed how suddenly the more serious or substantial ones progressively have lost shelf space, or have been completely dropped from most bookshops. It has become difficult in many chain bookshops to find a serious book of whatever genre on the shelves, which has been published more than six months before. It has also become a challenge for the less accessible authors, who tend to sell less, to find the protection of a publishing house with all their accompanying communications and spin machine they use to put him or her across to their readers.

The problem is that we really live in an age of Oprah or Richard and Judy book clubs. Much like some controlling parents, it is they who determine which book gets the pride of place in shop displays and, most importantly, who will top the charts. Umberto Eco once remarked in an interview that he saw no serious harm in excessive TV viewing by the least gifted citizens. Where he identified the danger to society was in TV viewing by the intelligent or the educated classes. Maybe the same case could be made for reading. So those who enjoy reading what we could call “the good stuff” should really ignore TV presenters. Why indeed entrust our reading habits to entertainers, instead of seeking inspiration from friends, or from the sometimes bilious book reviews in the New York and London Review of Books – to name the most famous and prestigious of these Anglo Saxon institutions?

It was therefore with a mixture of surprise and sense of vindication that over the past couple of years I have noticed the resurgence of the independent, smaller, occasionally themed publishing company. It is now possible, once again, to find some out-of-print women authors from the 1930s or read nineteenth century travel accounts. One can find regional authors to obscure texts from consecrated writers; from translations of authors previously unavailable or out-of-print, to the unearthing of old classics.

It is like the return of the vinyl record, only its triumph is already greater, for the readers of these books are still in thrall to the flicking of an actual paper page, to the showing off the book cover to others, to the physical hoarding of the object, or even to the bonding with the memory of having read it and being able to re-read it. This type of reader isn’t faithful to the e-book or to the online bookselling business, except for when it is the only place a particular title can be found. Without going to the extreme of what Ethiopia’s nineteenth century Emperor Menelik II did, who is supposed to have made a religious ritual out of chewing and swallowing of pages from the bible, it is nevertheless a source of satisfaction – maybe as mystical for some as Bible chewing – that once more you stand a greater chance of entering a bookshop and finding what you didn’t know you wanted. I say, what greater vindication of our genuine love for books is there than this? Vivat liber, vivat lector!