Joana Carneiro: The Maestrina Conducts Further Ahead

marzo 1, 2015

The Saga of a Novel: One Woman’s Story

marzo 5, 2015In an industry that is saturated with testosterone, the subject of female stature within the furniture and design world has historically caused controversy, along with an element of cliché. As long as the perception of women as the weaker sex pervades, the gender gap and the battle of the creative sexes will continue within many peoples’ working lives.

As a female student studying this sector of the design industry, it is impossible to ignore the fact that success stories in this field are primarily those of men. Historically, the importance of women as artists and crafters has been widely acknowledged, but furniture has been deemed very different.

Women have been largely excluded from furniture design because furniture is considered to be a microcosm within the macrocosm of twentieth-century architecture – and men have largely dominated that profession. The definite separation between male and female was hugely apparent in crafts production, especially in England in the late 19th century, wherein architecture and furniture were clearly men’s domain.

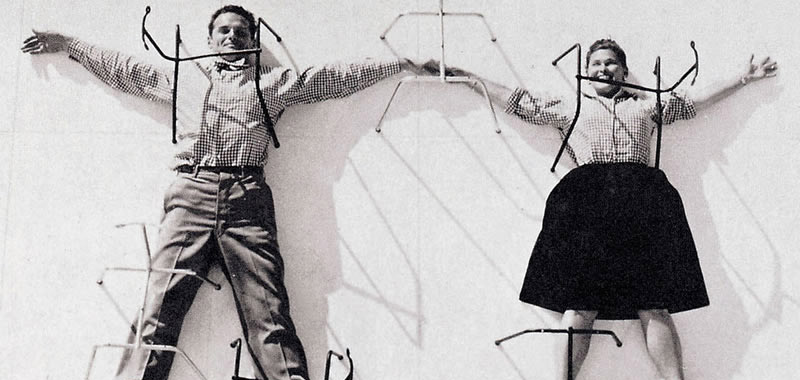

Against this trend, female influences have sprouted from a variety of design roots throughout the world. Shaker women, for example, are now deemed to be an important link between women as designers and women as makers. They not only worked as design directors on a range of projects, alongside the traditional craftsmen, but they also worked directly on the lathe. With heavy influence from the Christian faith and biblical reference to the relationship between Adam and Eve, they designed their furniture with care, believing that making something well was in itself ‘an act of prayer.’ In the twentieth century, females slowly began to be taken seriously as furniture makers in the Western world. Design heroines such as Eileen Gray (producing products ahead of her time), and Florence Knoll and Ray Eames, who worked alongside their husbands, created influential designs, such as the famous Eames Lounge Chair, which have shaped the industry of today.

Although the history of the field is filled with stories of struggle for female furniture designer-makers, the development of human rights and equality between the sexes has sparked a huge desire for young women to embrace their ambition and rebel against the strictures of this isolating design culture. As a young designer, I feel that the distinct lack of females within this industry is not just a boundary, but also a gap, which the industry must move to cross.

In many modern circumstances, it is still apparent that women are perceived as less competent in a workshop environment. Studying Product & Furniture Design at university and breaking into the field as a novice, led me to take a step back, look around and see the industry in a new way. Yes, the ratio of men to women is almost laughable, but why should I feel that I am inferior to my competition because of my gender? I most defiantly should not. My skill-set is such that I am much more capable using Makita power tools than a needle and thread; and I can assemble a three-tier, flat-pack storage unit in far less time than it would take me to create the equivalent cake formation in a kitchen.

In the current academic climate, specialised courses for women have been set up at establishments to accommodate those who wish to gain qualifications and diplomas in the field. Sheffield City College, for example, offers a Women’s Furniture Making Workshop. Lecturer Sue Clark explains that the course was set up ‘to encourage more girls and women to go into construction and the furniture- making industry’.

‘We run classes that give women the opportunity to develop their confidence and skills in an environment where they don’t feel they are the only woman in a group’, she says. I find this controversial in itself; surely creating a design course aimed specifically at women is isolating the students further, rather than working alongside males who are equally capable. Despite the rarity of influential female designers, many historical pieces and much of the success of design has been inspired by the physical female form. Well-respected and recognised designs, such as Verner Panton’s classic chair, are based on the female form with many artists and sculptors introducing forniphilia into their work in order to show perspective and beauty through design. This leads me to question the way in which male artists and designers express themselves. Does this objectifying phenomenon have a direct impact on the way females’ work is judged by comparison? It may be fair to say that the objectification of women in design has led to their own work not being taken as seriously as when females themselves are merely influencing – and that, passively – the design aesthetics of men.

When talking to influential businesswomen within the industry, the subject of women in design is often seen as a cliché and almost irrelevant. This conventional wisdom, however, leads me to question the obvious: does it make sense that a consumer base of 94% female continues to be served by a nearly all-male designer/producer class? The industry, the media, as well as academia have ignored the question and there is no hard data documenting the state of the industry. Although the number of female graduates from manufacturing-based design courses is on the rise, the number of women in the industry is still minimal. The backbone of all the main manufacturers and dealers seems to be made up of almost exclusively male vertebra.

Young female carpenter

It is becoming more and more obvious, especially in the current climate, that it is not what you know, it is who you know that is important. No employer will take a look at your first-class honours degree unless you have your foot outside of the small university pond and into the dangerous ocean of reality – that is in the industry, where the key is competition students ‘push social boundaries’ when enrolling in manufacturing courses, but the missing link comes when universities don’t provide sufficient resources, knowledge and, more importantly, advice on how students can expect to use their talent in the real world. ‘Cotton-wooling’ students into thinking that their life decision to be a sole trader or freelance designer will be an easy ride leads to graduates finding their encounters with the real world to be a blow – resulting, in many cases, in a loss of passion. In my own transition, I became absorbed in the business side of the industry and the culture that comes with it. I used my initiative (and persistence) to gain various placements in well-respected companies throughout the industry. This was the most sensible decision I have ever made. Although many people find my passion and knowledge for manufacturing ‘refreshing’ for such a young girl – I envisage this as a stepping-stone. Young people my age, yet to graduate, are grasping opportunities which could lead them to higher places. This fresh ambition and drive are what companies desire. The industry is swamped with young professionals in their late twenties, all reporting to ‘wise owls’ in their late fifties, few of whom are women. This is where the gap should come to light and make young females realise that the competition is healthy and not a boundary – women should no longer be seen as inferior and/or a novelty in this industry. It is time to embrace the passion and seize opportunities. In the current economic climate there is no time to waste. It seems employers sometimes may not know what they are looking for unless you show them. The key message, exemplified by the likes of Eileen Gray, proves that gender is insignificant as long as you have enough ambition and talent to prove yourself as an individual.