COMITÉ ESPECIAL DE DESCOLONIZACIÓN DE LA ONU,

noviembre 8, 2022Luminous decorations add to the electric glow that conceals the stars above the city buildings. At the darkest time of year, the blazing streets light the way for crowds of shoppers. They are drawn to the cathedrals of capitalism like moths to a candle. Every year, commentators raise the objection: ‘We have lost the true spirit of Christmas’. What does this consumer frenzy have to do with the birth of Jesus?

by Mike Hawthorne

The answer to this question is ‘nothing’ on many more levels than is usually appreciated. Since the existence of a historical Jesus remains uncertain, so does his birthday. However, the winter solstice marks the traditional birth of other ancient divine redeemers, notably Mithras, ‘The God of Light’. The more one examines the official gospels, the more one discovers elements of other redemption myths within them. Most obviously, the Jesus stories borrow from the Hebrew Messiah, as an anointed liberator; Dionysus, with the imagery of bread and wine; and Mithras, as ‘The Light of the World’. But that is only the tip of the iceberg. Many of Jesus’ parables echo the Stoics and Pythagorean philosophy. Soon, we realise that the only original thing about these tales, is the way they have been assembled. Jesus, the Graeco-Roman Joshua, is essential for dramatising the message. He is the cornerstone, but in a literary, not a literal sense.

The fabric of early Christianity is a reflection of the cultural discourse of Hellenised Jewish communities in first-century Tarsus and Alexandria, weaving new patterns onto an Israelite backcloth, to escape the dead hand of the dogmatic priestly cult in Jerusalem. The Saviour’s passive crucifixion and rejection of violence lend credence to the theory that the ‘biographical’ gospels were written with hindsight, after the brutal Roman destruction of Jerusalem. Paul of Tarsus, for example, is unaware of the crucifixion in his early, unforged, letters. After Paul, the Jerusalem temple priests were dramatically exposed when their Holy of Holies was looted by the imperial legions. Armed revolt was futile. Early Christianity proposed to permeate the world, at all levels of society, by stealth and infiltration, not by the sword. The sword came much later, with Constantine, when the oppressed stepped forward to become the oppressors. After that, an empowered, violent Christianity ‘gained the whole world, but lost its soul’.

As the new Imperial state religion, the Roman Church needed an annual calendar of events for public celebrations. Previously, all kinds of cults had flourished alongside the classical pantheon. The Christians ended this tolerance abruptly at the beginning of the fourth century. The exclusive, male mystery cult of Mithras was wiped out. It had been popular among the Roman legions, the real power behind the emperor. Followers of Mithras were tightly organised into secretive groups of initiates worshipping in underground caves and temples. When they smashed these temples, Christians often built on top of them. The soldiers became proto-crusaders, ready to slay or convert pagans at the point of the sword. The cross itself was an old emblem of Mithras, as was the halo. The Roman priesthood adopted Mithraic practices, such as the name ‘father’ and the colours of the vestments of their bishops and cardinals. They made December 25, the day Mithras was born of a virgin among animals and shepherds, Christ’s birthday too. The new faith had already absorbed the God of Light and Eternal Life into the composite figure of Jesus Christ, so it is not surprising that other convenient practices were incorporated.

Human beings have been evolving for millions of years. For the vast majority of that time, nothing was written down. As they emerged from prehistoric oral traditions, the first examples of writing mixed creation myths, heroic legends and local histories into our earliest literature. What had previously been dynamic and changing with every new generation of bards, now became static, fixed by the scribe’s pen. The written word acquired authority over the spoken, simply because it was written. The older the text, the more it was venerated, because it was presumed to be nearer the source – in other words, just because it was older.

The Israelites produced their core scriptures to preserve their cultural identity during their exile in Babylon. As a subjugated people, they adapted and transformed myths from the two mighty Mesopotamian and Egyptian empires that surrounded them to create a hybrid tribal identity for themselves. After eliminating the female consorts of such Canaanite gods as Jehovah (a mountain demon), and the sky god El, they merged them into one nameless abstraction that spoke through prophets. Their Torah bulged with half-digested Egyptian, Hittite and Assyrian mythology and a catalogue of petty rules and superstitions collected by their priestly scribes. The heroic prophets of the Babylonian exiles, the patriarchs Abraham and Moses, were wish-fulfilling fantasy figures that led their nomadic clans towards a sedentary existence centred on Jerusalem in a ‘land of milk and honey’. In the end, it was no prophet but a liberating Persian king who allowed these ‘nomads’ to return to Jerusalem and be horrified by the behaviour of its population who, in the absence of the zealots, ‘whored after strange gods’. There would have to be a purge.

By creating the first recorded ‘minimalist’ religion, in which the temple housed an empty space instead of a statue, the Jerusalem priests forced observant Jews to confront the void. After the Jewish rebellion in the year 70, the temple itself was in ashes. The Hellenised Jews of the Mediterranean coast heard terrible stories of how the surviving defenders were crucified by the hundreds, in deliberately obscene positions, around the ruined walls of the city. The most pitiful, despised, wretched creature imaginable was a crucified Jew. There was nothing lower. The first Christians, with their upside-down, ‘first-shall-be-last’ worldview, had found an image for their Jesus, caught between hypocritical priests and brutal soldiers.

The smashed temples of Mithras remain under today’s churches. Recently, one was excavated in the City of London. Its statues and artefacts are in the Museum of London and the temple’s foundations have now been bought by the financial-information provider and media group Bloomberg. (It is building on top, only after allowing historians plenty of time to carefully check the site.) However, if you go into the countryside on a clear night, far from the Christmas bustle, and look up at the great constellation of Orion, you might catch sight of Mithras as the ancient Persian stargazers first saw him. The void is full of drama. The God’s dagger plunges into the Pleiades on the neck of Taurus. He seems to carry up the sun as it rises, moving the heavens to bring us renewed life. You’d have to ask three wise men from the east how Jesus fits into this picture. In the current Age of Mammon, the Saviour’s birthday celebration constitutes the biggest annual spike in the retail sales graph, as Bloomberg can doubtless confirm. The murder rate, especially within families, also peaks. It is easy to imagine how a character like Jesus would react to such an exaggerated orgy of materialistic greed in his name. He would be kicking over the tables of the merchants and moneychangers until they’d have to nail him up all over again.

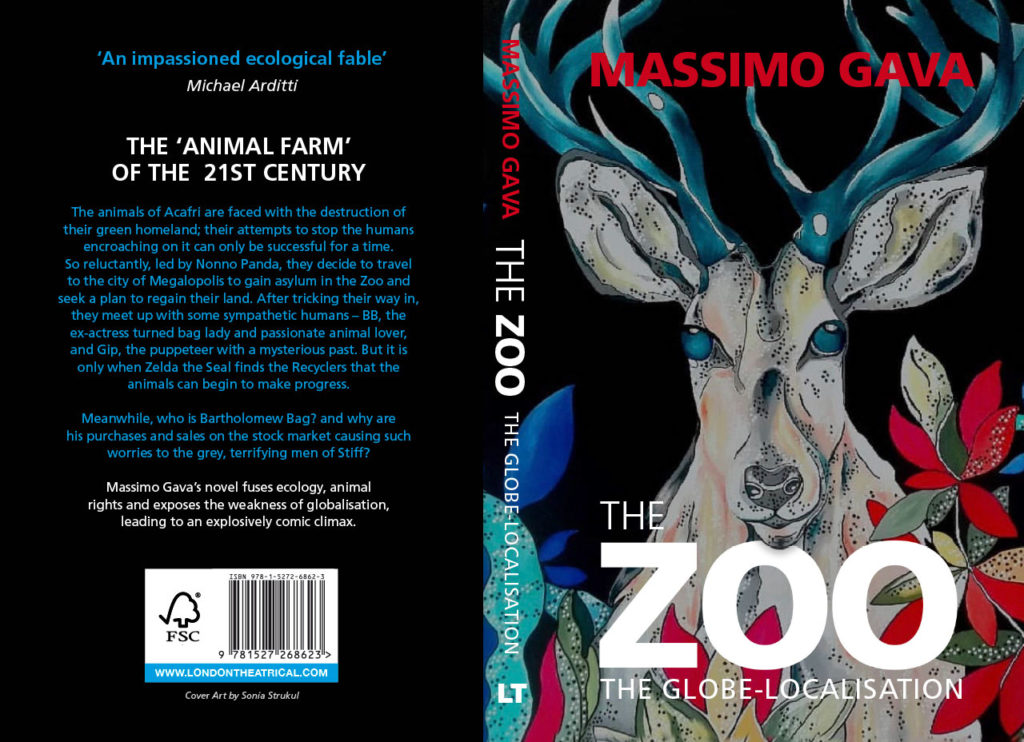

https://www.ebay.co.uk/itm/143752055296

https://www.waterstones.com/book/the-zoo-globe-localisation/massimo-gava//9781527268623