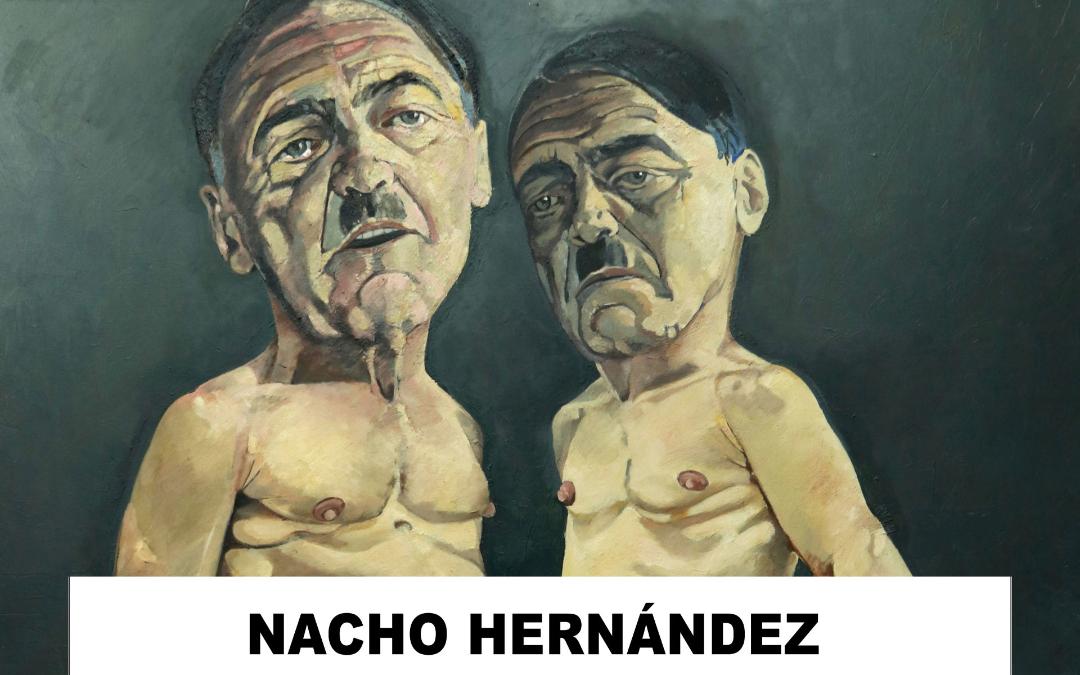

El mundo de Nacho Hernández

febrero 15, 2022

The Globe-localisation or Animal Farm of the 21st Century? A review of “The Zoo”

mayo 30, 2022The Reality of Disguise – The Policeman

There’s a story that’s been going around for years, told and retold of the ‘Carnival Policeman’ whom I happen to know. It seems that even though this is not a new story the Portuguese saying of “he who tells a tale adds a dot” hasn’t changed it much. This cop friend in order to make some more money doubled as a bouncer at a well-known nightclub in Lisbon. One Carnival night the club organised a fancy dress competition, with one theme: uniforms. Throughout that evening people of all shapes and sizes walked past the ‘Policeman’ as soldiers, nurses, doctors, pilots, airhostesses, priests, nuns or cardinals. The award was enticing: a return trip to Brazil.

The ‘Policeman’, engrossed by this show that started well before the ‘disguised’ patrons entered the club, fascinated with the way they walked, posed and picked on each other, couldn’t find among them a single contestant wearing a police uniform. So tired of the fact then that he was working at a party and not part of the party, he asked the doorman to give him a minute as he had had the idea of joining the competition disguised as who he was in real life, namely, a police officer.

So he walked in the dark and (back then still) smoky nightclub and placed himself last in a queue of other people in uniforms dreaming about getting those free holidays in the sun. There was a jury, who didn’t take long to inspect each one of the contestants and to come back with a decision, which was announced with much aplomb by a presenter: “The winner is the person disguised as Policeman!” My friend couldn’t believe his luck. Ironically, or maybe not, he had won a fancy dress competition wearing a disguise of who he really was. Like if he was looking at a mirror reflecting himself for all eternity, or as if he was in Pessoa’s “Autopsychography”:

“The poet is a faker

“The poet is a faker

Who’s so good at his act

He even fakes the pain

Of pain he feels in fact. ..“

Living the Life Unlived – the ‘Woman Doctor’

This special and rare coincidence of disguise and disguised speaks to maybe one of life’s greatest questions. How one deals with it in a way dictates how well we cope and how sane and functioning we are deemed to be. In psychoanalyst Adam Phillips’s book, fittingly called “Missing Out – In Praise of the Unlived Life” he examines the way we deal with the life we think we should be living and not the life we were handed. How much of our mental life is in fact about the life we are not living?

In Phillip’s words: “Indeed our lived lives might become a protracted mourning for, or an endless tantrum, about the lives we were unable to live.”

An acquaintance of mine reminded me the other day of another curious carnival- like story. Like most other stories about slightly different characters of Lisbon this one takes place in a particular area of the city: the Chiado district, Lisbon’s equivalent to Broadway, or the West End. This is where the upper classes used to shop, where most theatres and the only opera house are and where bohemians, artists and people who enjoyed standing out even from a crowd of artistes drank their coffees and bitter almonds.

Their favoured haunt or local was a café called ‘A Brasileira’, first place in the country to serve ‘bicas’ or espressos, now better known for a much photographed life-size realistic statue of Fernando Pessoa (another of the café’s former patrons) sitting outside. This café, teeming with paintings by some of the best national painters of the 1960s and 70s, has had its fair share of personalities over the years. Like the two sisters who, upon arriving for their daily caffeine and gossip shots and seeing their usual seats taken, would slip out a small, thin but painful sewing needle and proceed to prick the all too quickly unhappy occupants of what they considered their property;

Or the, maybe less usual character the ‘Woman Doctor’. This middle-aged woman, always impeccably attired in medical garb – a virginal, spotless white doctor’s coat, hanging stethoscope and small bag carrying other diagnosis-enabling paraphernalia – would enter ‘A Brasileira’ with the hauteur of stubbornness and work the room, walking from table to table catching customers between the shock of surprise at having their wrists felt and arms grabbed for blood pressure and the reluctance to defy a naturally powerful profession. The ‘Woman Doctor’ would, after each appointment, write a prescription in illegible writing, thus adding to her credibility. She would disappear as fast as she came and would only be seen doing this in this most august of institutions of the Chiado.

Until, one day, a friend walking down Liberty Avenue, Lisbon’s main boulevard, came across this ‘Woman Doctor’ in plainclothes. As he approached her to comment on an outbreak of flu in the city he found he was cut short by her imperious and polite retort that she would only conduct “appointments at her practice “.

No one knew or found out more about her. She appeared as quickly as she disappeared and hasn’t been seen in years. Was she living her unlived life?

One can certainly speculate that the woman behind the Doctor character was maybe refusing to accept, in Adam Phillip’s words “the gap between what we want and what we can have”. Albert Camus defined this as “absurd” which he saw as the initial belief that the world was made for us. The way and the how we wake up to Freud’s “reality principle” determine how we cope. In other words our ability to feel satisfied is directly linked to our capacity to handle frustration at not getting what we feel we are owed or at (in Phillip’s terms) “not getting away with it”.

In Praise of Madness?

Living in Lisbon is living in the capital city of the country that, maybe as a whole, sees itself as living a life completely different from the one it feels it ought to have. It also means observing throughout time how people have resorted to grand prophetic traditions like that of the Fifth Empire, that of the Holy Ghost, a mixture of an ancient Persian Nebuchadnezzar Book of Prophecies myth and of a centuries’ old manuscript by a shoemaker called Bandarra, or a Messiah complex whereby the city awaits the return of King Sebastian who disappeared in 1578 on a North African battlefield thus accelerating a downturn in the country’s fortunes and precipitating an eighty-year-long period of Spanish rule.

These phenomena are described by that perfect embodiment of a XXth century renaissance man, Michel Foucault, in his opus “History of Madness”. Lisbon could very well be the ‘Narrenschiff’, a ship of fools, which Foucault elaborates on. Mad, crazy, eccentrics alike are not only prisoners on it but also of its voyage itself. This is a city at the end of the line; no-one comes to Lisbon while travelling somewhere else (except for a brief period during World War II when the city became a gateway for refugees seeking safe passage to the Americas). The city is like a ship stuck at the wide and hungry mouth of the Tagus looking out to sea and, in a way, having lost the ability or confidence to take the plunge.

Much like Arnaldo, the eternal groom or the night painter, a tall man, perfectly attired in morning jacket, pearl lapel button, polished shoes with an extremely loud voice, who epitomised the confusion that Carnival may signify. He posed as a groom, freely giving out stories about how he went mad with grief at being rejected at the altar by his bride. He would use that as justification to harangue, threaten, and punish what he saw, in his moralistic and petit bourgeois perspective, as the evils of the city and the world. But what he actually was, was a boring repetitive painter, who wanted to force others to see things as he saw them, in darkened, night-like pastel colours.

Naturally we all prefer the grander, more creative thrust of madness and maybe its capacity for that very special type of melancholy that to Victor Hugo is “the happiness of being sad”.

We would all be more in thrall of a person like the ‘Conductor’, an older man who used to be seen dining regularly in the same cheap and cheerful restaurant in central Lisbon and who once invited a friend to a concert at his place. This friend, convinced he was going to hear a soloist in action, went along. To his surprise when he arrived at the man’s half-lit flat, he was sat on the sad worn sofa and then his host picked up a couple of batons and started conducting his orchestra to a record playing Mahler’s Fifth Symphony! For all his theatricality, my friend told me, one could see how he was utterly convinced he was creating something new and never before seen, persuaded, like Don Quixote, of his greatness and of his “service” to humanity.

We would likewise be fascinated by the “Blank Writer”, a man who would sit day after day in a café writing dozens of pages that he would meticulously, in a zealot-like furore, obliterate at the end of the day. As Portuguese poet José Manuel dos Santos said “one creates, leaving nothing, the other bequeaths without creating”.

As Eustache Deschamps, the French medieval poet, would say:

“On est lâches, chétifs et mols,

Vieux, convoiteux et mal parlant.

Je ne vois que folies et fols

La fin approche en véritéTout va mal.

“We are cowards, weak and puny, old and envious slanderers; all I see is madmen and madness, the end is truly nigh, it all bodes ill”

Adeus, Goodbye

Very much like João Manuel Serra, the final character in our survey, who was known as the ‘Gentleman of the Goodbye’. At one time he had lived in a large house with a large privileged family. He still had some relatives who he didn’t wish to burden, but no longer the big house. He always wore his signature dark thick overcoat, whether it was summer or winter, warm, or cold and with that, some equally thick-rimmed spectacles. He had something of a Vincent Price quality to him. Anyone could see he was lonely and this is what took him, every night, to one of Lisbon’s main round-abouts, the Saldanha, where he would graciously wave at passing cars, smiling as cars honked back at him while drivers and passengers alike, with that warm feeling of not feeling threatened by another’s difference or eccentricity, would wave back or bid him good night. Towards the end of his life he became a celebrity, increasingly appearing on TV, in documentaries and sometimes even being caught doing something social, like going to the cinema, with friends.

He was the madman, who was neither kicked out of the city in a Narrenschiff nor interned in an asylum. He was the harmless fool that did not torment us with his torments. Unlike Bosch’s Lisbon painting of “The Temptations of St Anthony” where madness is a cosmic manifestation, with João Manuel Serra it becomes a subtle dialogue of man with himself, a translation of our weaknesses, failures, illusions and dreams.

Robert Musil looks at madness as a sort of “intellectual romance of modern times”. In a way, according to Foucault, the madman reveals the most primary truths of man, and madness becomes a “chronological, organic, sociological, psychological childhood of man”. French XVIIth century physicist Philippe Pinel said “how alike it is to manage the alienated as it is to educate the young!”

At a time when the air reeks of a certain malaise or “ is empty”, as George Lipovetsky argues and we are witnessing the rise and rise of individualism over the social, of the psychological over the political, of diversity over the previously reigning homogeneity and, finally, of permissiveness over discipline, it is surely right that we celebrate a degree of non-conformity and madness during this carnival time, because, as Pessoa said in his poem on the messiah King Sebastian taken from his book “Message”:

“Without madness what is man,

other than a wholesome beast,

a deferred corpse that procreates?”