JOANA VASCONCELOS. The world of yesterday today

Febbraio 17, 2014

What Makes an Artistic Genius? Anna Paola Cibin – the fairy tale continues.

Maggio 30, 2014Creative minds have always been inspired by nature and the sharp contrasts of winter are no exception.

Philip Rham offers an overview but quickly homes in on the heart-warming magic of Christmastime and how Tchaikovsky’s ballet “The Nutcracker” embodies this spirit in abundance and allows you to disocver that wide-eyed wonder of your childhood again.

Winter over the centuries has inspired creative minds to great feats of invention. It is a season of sharp contrasts. On the one hand, the coldness and freezing nature of this time weigh heavily where hibernation and survival are the order of the day. The fl ip side is to escape from this dark and merciless cold by creating a warm, fi re-fuelled space inside, analogous to the human warmth of Christmas cheer and the generous exchanging of gifts to loved ones; despite its appalling modern-day commercialism, it is undeniably the time for families to come together and above all a magical time for children to indulge in their imaginations, the excitement of Father Christmas and the dizzy prospect of ripping open presents.

In art we immediately think of Brueghel and his snowy landscapes dotted with peasants struggling on as well as letting us glimpse a few skaters having some fun. The bleakness of the winter experience is no better conveyed in literature than in the Russian literary canon from Dostoevsky’s “Crime and Punishment” (Raskolnikov driven psychotic by hunger in his garret), through to Pasternak’s “Dr Zhivago”. On the other hand it is primarily Dickens in the English-speaking world who captures that “Tis the season to be jolly” mood in his novels, most notably “Pickwick Papers” and naturally “A Christmas Carol” , all punch, holly and ivy and roaring fi res accompanied by groaning tables of festive fare. These are the scenes that Victorians, dare I say it, fantasised about and that are so beloved of Christmas card manufacturers!

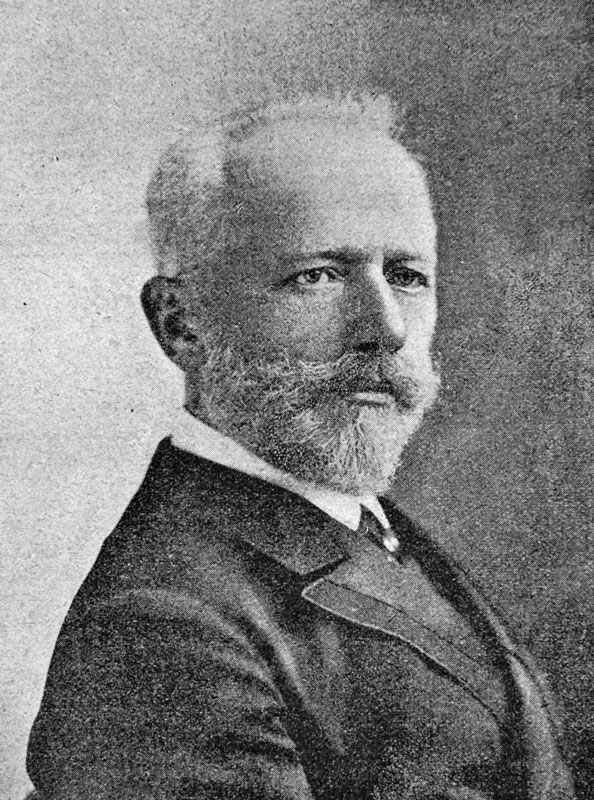

However it is in music that this contrast of styles is so richly embodied. Once again our friend Vivaldi (see my article on Vivaldi and springtime Dantemag 03/13) vividly portrays the freezing trials of this season, only briefl y alluding to sitting by a fi re while the howling winds batter at the doors. Indeed it was much earlier that Jean-Baptiste Lully in his opera “Isis” from 1677 set to music “L’hiver qui nous tourmente” with its famous shuddering tremolando descending phrases, so memorably pinched by Purcell for his evocation of Winter in his “The Faerie Queen” in 1692, which ironically has become much better known.. More recently I could quote the “Sinfonia Antartica” by Ralph Vaughan Williams with its chilling evocation of that windswept blanked-out landscape and many of Sibelius’s works take their inspiration from the Finnish fi r forests blowing in the cold northern winds. However where do we have to go to fi nd music that encapsulates the warmth, the magic wonderland which is the meaning of winter and Christmas for so many of us, especially our children? We need go no further than Peter Ilyich Tchaikovsky’s ballet “The Nutcracker ”. Nothing in creative form so epitomises the festive season than this remarkable ballet. Indeeed it has almost become the Christmas banker for so many companies. Has familiarity bred contempt? I will argue that it has not, if entrusted to an imaginative creative team. Once again, like Vivaldi’s “Four Seasons” I talked about last time, this ballet was not always the hardy perennial it has become today.

The original E.T.A. Hoffmann story called “The Nutcracker and the Mouse-King”, written in 1816, has a heroine called Marie, instead of

Clara, and, in true German Grimm fairytale fashion, is much more gruesome in nature – there is still a Drosselmayer, the inventor and magic toymaker but the Mouse-King has seven heads as the mice emerge from the fl oorboards and do battle with the toys and the Nutcracker. The Mouseking’s daughter Princess Pirlipat is cursed by the Queen of the Mice and is given a huge head, a wide grinning mouth and a cotton-wool beard, which monstrous fate is passed on to Drosselmayer’s nephew, who had broken the spell on Pirlipat. Marie, by her kindness, rescues the Nutcracker/Prince who fi nally returns triumphant with the slain Mouseking’s seven crowns and whisks Marie way to the land of dolls and many wonders.

She returns to her real home and nobody believes her story even though the seven crowns still lie there.

It was Petipa, the great Russian choreographer, who had the idea of making it into a ballet but by now a new, less vicious version by Alexandre Dumas père had gained the upper hand and, somewhat reluctantly at fi rst, Tchaikovsky agreed to write the music for it. The ballet premiered in 1892 but to a very luke-warm reception; what immediately proved to be much more popular was the “Nutcracker Suite” which Tchaikovsky wrote and published earlier, as he was now desperate to be the fi rst composer to feature the newlyinvented “celeste”, so-called for its heavenly bell-like sounds and of course “The Dance of the Sugar Plum Fairy” is now synonymous with that instrument. However, while the suite continued to be performed, the actual ballet quickly fell out of the repertoire. Just think, it took until 1934 for it to be produced in the UK for the fi rst time and not until 1940, in its complete version, at the San Francisco ballet. You might well argue that it was certainly already well-known, especially after the release of Walt Disney’s “Fantasia” in 1940 but once again it is the suite Stokowski and the animators drew from and, to a certain extent, one could justifi ably maintain that the fi lm’s clever and witty representations of the marvellous music are now what people immediately associate with when they hear the Dance of the Snowfl akes, the Chinese dance or the Russian ‘trepak’ dance or, indeed, the Sugar Plum Fairy.

Balanchine it was who revived it in a slightly modifi ed version for the New York City ballet in 1954 and this started the trend that from the sixties onwards meant every ballet company in the world now programmes “The Nutcracker” at Christmas.

The ballet, as we know it today, has Clara and Fritz as the children of a well-to-do German family, the Stahlbaums, celebrating Christmas Eve, decorating the magnifi cent tree and inviting honoured guests. One of them is a toymaker and magician, Drosselmayer, who brings life-size toys as presents, including a Nutcracker for Clara.

During the night she sneaks down to check on the toy and it is now that the magic begins. A great coup de theatre occurs at midnight as the tree suddenly begins to grow and grow, the owl on the top of the clock becomes Drosselmayer and suddenly mice come out of the fl oorboards and headed by the one-headed Mouseking do battle with the toy soldiers led by the Nutcracker, who, in the meantime, have all come to life. It transpires that the Nutcracker is Drosselmayer’s nephew, a handsome Prince who had been turned into a hideous Nutcracker as a curse. Tin soldiers and dolls carry away the wounded prince, who whisks Clara away to a moonlit forest where snowfl akes dance around them. Act II sees the pair being transported in a nutshell, drawn by dolphins to the Land of the Sweets and in Clara’s honour, there follows a succession of excuses for various national dances, chocolate from Spain, coffee from Arabia, tea from China, Russian candy canes dancing the trepak, Danish shepherdesses dance with fl utes, followed by Pulcinella and then beautiful fl owers dance, rounded off by the great pas de deux of the Sugar Plum Fairy and her Prince Coqueluche. As a grand fi nale all the sweets do a grand waltz.

The Prince and Clara are crowned King and Queen of the Land of Sweets. Then Clara wakes up and fi nds herself under the tree, lying next to her Nutcracker. So it was all a dream – or was it? because also there lying right next to her is her crown.

It is quite obvious from just listing the sequence that any dramatic drive judders to a halt in Act 11 but the point is to let yourself be dazzled by the exquisite music and the breath-taking dancing.

Just go with the fl ow, forget your intellectualism and sit back and enjoy the magic, as if you really were in a sweet shop, in fact, in a ‘Charlie and the Chocolate factory’.

‘Oh no, no, no’, I hear you say, ‘I’m O.D -ing on sugar just reading about it!’ Naturally, it all depends on the production. In the hands of an imaginative director and designer, it truly can be a phantasmagoria of colour and spectacle and what pleasure there is to be had in being enchanted and feeling like a wide-eyed child again. Needless to say, there have also been revisionist versions, namely Mark Morris’s retitled “The Hard Nut”. He was inspired by renowned American graphic artist Charles Burns, whose dark explorations of child sexuality certainly put a different gloss on the work! More recently, Matthew Bourne – he, of the hugely successful up-dated “Swan Lake” – had the bright idea of setting it in an Oliver Twist-like orphanage and, as he is wont, wittily renaming all the characters with a stronger sense of Clara’s awakening sexual emotion but still with an intoxicating inventiveness and fun. So wherever you are in the world, what better way to forget the cold, dark, bleak midwinter outside than to dive into a cornucopia of Christmas warmth and cheer and let Tchaikovsky, through the medium of ETA Hoffmann and Alexandre Dumas père’s original story ravish your senses with the sheer beauty of his music and taste the delights of “The Nutcracker”. I urge you to become a child again, rediscover the magical warmth of spirit that surely must be the prevailing emotion of this contrasted time of year – at a ballet near you, without a shadow of a doubt.